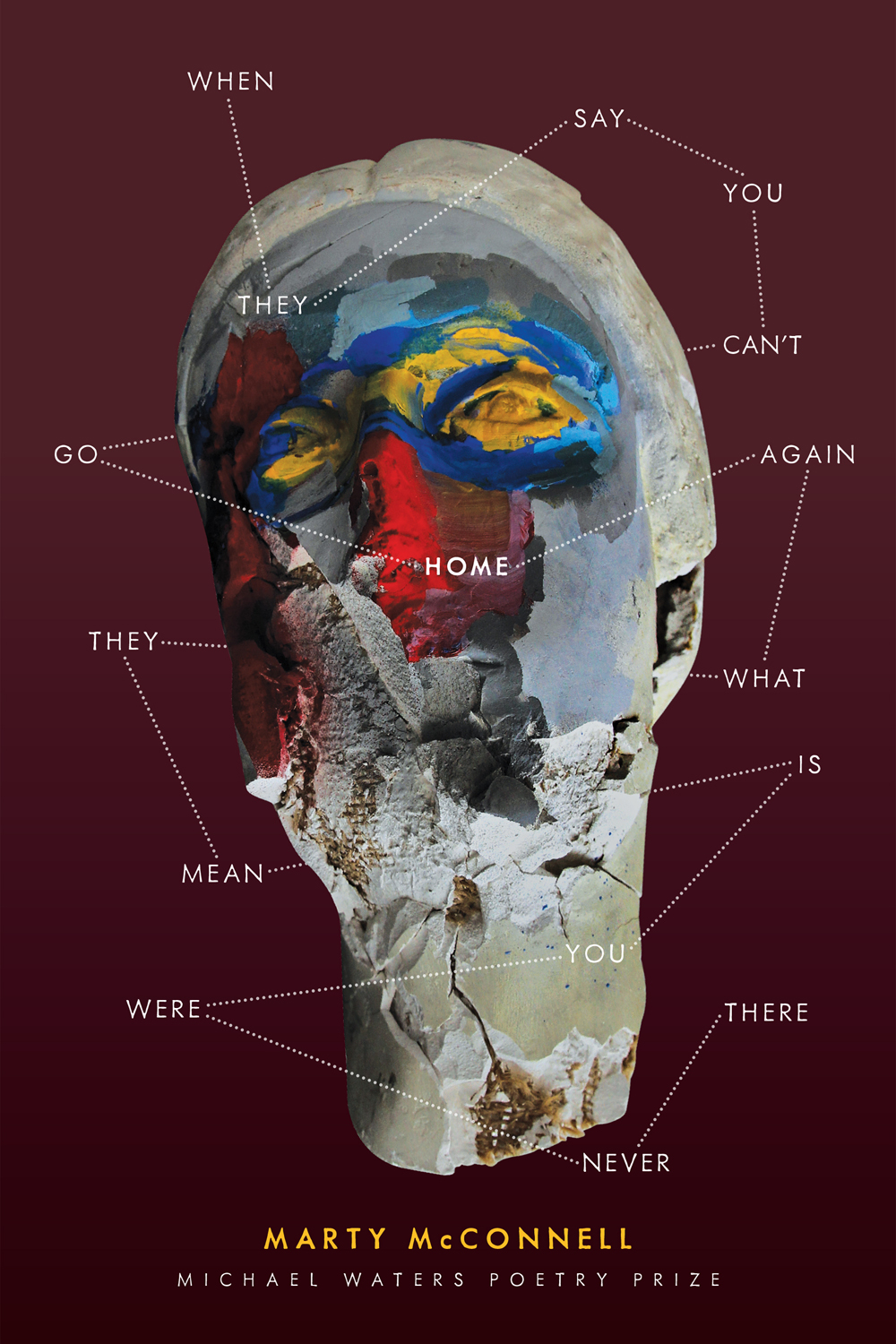

‘when they say you can’t go home again, what they mean is you were never there’ by Marty McConnell

Author: Julie Marie Wade

January 14, 2019

First:

It has been sixteen years since I last set foot inside my childhood home. Even then, on Christmas morning 2002, I knew I would not be coming back. We had reached that fabled impasse—gay child, Christian parents—foretold in books and films: the queer life I would not repent; the queer love they would not, perhaps could not, forgive.

Sometimes I want to write a better story for us, something less clichéd than “love the sinner, hate the sin,” “you’re going to burn in hell,” and “in this house, we believe marriage is between one man and one woman, period.” Didn’t I at least deserve an ellipsis? Instead, I left with an interrobang: “Do you really expect me to forsake my heart, the same heart you told me to follow?!”

Of course I wasn’t eloquent, wasn’t composed. Of course I wept in the car, sent letters, wrote rebuttals disguised as poems. Making peace takes a long time, I’m learning. Even now, 3300 miles from my first home, I think of the family I left behind. I’m still sad, but I’m not sorry. I wish I could explain. It’s as if I was never the daughter they thought they were raising. It’s as if coming out was not in fact the cause of our severing, only one inevitable effect. It’s as if—but this is as far as I ever get.

Then:

The week before Christmas 2018, Marty McConnell’s new poetry collection arrives in the mail. Her title completes a sentence I have tried so long to finish in my mind: when they say you can’t go home again, what they mean is you were never there. The linguistic see-saw tips at the comma, and I feel something like elation, something like relief, sliding down the other side of that line. I scan the Contents page for a poem by the same name and find it, a poem that includes this remarkable triptych:

________Part of me died here

___so another could go on walking the path on the hill

where I became larger than myself and the day

________</spancould no longer contain me.[Here’s the elation—I go on!]

And then:

________What I cut off kept walking

____________________________without me.

__________________________________________[Here’s the relief—they go on too!]

And then:

__I’m not finished yet. Somebody

kiss me now, right in the garden.

____Everything’s coming up green._______________[What is this feeling? Ah, resilience—the prospect of a second chance!]

After:

I read McConnell’s book several times over winter break. I didn’t want to put it down. There were many uncanny moments, like when my partner was driving through the Great Smoky Mountains while I peered out the rain-streaked window. A huge yellow sign warned of “Falling Rock,” and the poem on my lap echoed: “In an area// with a history of avalanches, signs are posted: Falling Rock.” Once again, art and life seem deeply intertwined.

My partner and I often road-trip from Florida to Kentucky for the holidays—to see some of her family, who are my family too, the ones I call my Outlaws. It takes two days, sixteen hours solid road time. Behold McConnell’s prophetic poem “radio silence, WENZ, WJMO, Cleveland,” which begins:

I start down the road but I’m the road. Or

the stripes on the road. White. Edge-

indicative.

I think I know where we’re going, think I’ve been here before:

A road is practical. Stoplights, guard rails, signage

regarding the merging of lanes:

practical.

Then, we swerve:

_____________I started

down this road and now I’m the road so

here: a man waited 1.5 seconds

to shoot a Black boy playing

with a toy gun. The man

was a white man. Police

man. The boy was 12, was Tamir, is

dead. […] I start down the road

but I’m the gun.

Now we’re skidding on the poem’s hard truth, spinning out on the ice that doesn’t melt:

________It’s important

To say this. It is a thing my people

did.

McConnell makes all the essential swerves, I’m learning. What is a volta but a swerve—a turn with a “v” in it, that higher voltage?

When I turn/swerve to the next page, two prose poems appear side by side like lanes of traffic: “the sacrament of penance” and “the sacrament of hope after despair.” I marvel how the poet has placed these poems exactly where they are needed, exactly when they are needed. I marvel how she anticipates and honors each reader’s fractured heart.

The first sacrament begins

I come to claim the white boy who yesterday slaughtered nine

Black worshippers at prayer. Because to deny him is to deny the

ways he and I are the same, deny the hideous lineage that dogs us

and feeds us. Gavel and spit. Rope and bumper and chain. I claim

him but will not say his name.

The second sacrament begins:

How many men must we survive? The fortysomething at the screen

door when I was 15. Roses on the porch whenever Dad was out of

town. The one who tried to rape me. The other one who tried to rape

me […] The one who made me and broke my mother’s heart.

There is penance for white privilege—for what it means to wear a white face in a racist world. There is despair for female subjugation—for what it means to bear a woman’s body in a misogynist world. It is the same person, privileged and subjugated, wearing and bearing; it is the same world. The promised hope comes in the final inset stanza, far from the left-hand margin—a visual stretch. Like a buoy, this stanza offers something to reach for. Like a speed bump, this stanza offers something to slow for:

Oh my nephews. Oh my godson.

You do not have to be women

to be kind. Look at your fathers, wounded

by their own fathering, how they make

tea and hold you. Destroying

nothing. Killing no one.

Now:

In any review, there comes a moment when readers will expect a synthesis. So, what kind of book is this book, overall? Tell me: What am I reading for or toward?

Ok, here goes. When they say you can’t go home again, what they mean is you were never there is a deeply intersectional project. It’s feminist, queer, and attuned to the many sites of self that comprise one person. It’s also a love story between two people, two women-people, epitomized by titles like “love in the Late Holocene.” It’s also a work of what I would like to call secular eschatology, perhaps even eco-eschatology, meaning a book concerned with last things—among them, the fate of our planet and the ultimate destiny of humankind.

In the invocation poem “come now, let’s sit in what light is left,” McConnell’s speaker confides:

________I know

this world is going

to end, I feel it

This sentiment—a poetic thesis perhaps—is echoed many times throughout the book, always as an occasion for deepened reflection and also as a new place to pivot: “How shall we pretty for this ruin?” and:

Here’s the trick of being alive.

in a dying time: there’s neverany proof. Animal, vegetable,

mineral is now rock, water,

scissors. Now milk, salt, milk.Still want that skin?

And:

a thing

the movies got right: the prepared

fare no better than the foolish. It’s all

as it was written, erased, traced over,

scribbled on by toddlers, and read aloud

in the bath. No apocalypse an end,

not even ours.

What’s that? You’re looking for a map, you say? Well, you’ll find five of them here, interspersed between the poems—six if you count the cover. But the truth is, McConnell’s intricate diagrams—my instinct is to call them word-webs—won’t take you point by point toward a single destination. Early on, her speaker makes clear: “I don’t know how to end this.” Her diagrams are illustrations of this fact. Instead, you’ll move recursively and multi-valently through these poems and around the webs that mark spaces (social, geographical, interior) in lieu of maps.

For each, a hub-word appears in bold: the first is light, followed by time, death, Anthropocene, and body. Perhaps these are guidewords set loose/ thrown clear from a dictionary in a crash. Perhaps these are the guidewords that swerved. I like to imagine someone asked McConnell what her book was about, and she said, quite sincerely, “Here, let me draw you a map.” I like to imagine these word-webs are each of the maps she drew.

You’re looking for patterns, you say? Well, beside the word-webs—in which you’re meant to get tangled, by the way, meant to get lost—there’s the religious lexicon sweetly queered and deftly secularized at every turn/swerve: “supplication with grimy windowpane,” a series of sacraments including “the sacrament of penance also has four parts” and “the sacrament of holding hands,” and that final, glorious, anaphoric poem, “actual rapture,” which twice repeats its powerful send-off line, “Day nobody dies.”

There’s also a stunning particularity when it comes to place in this book—poems like “West Barry Street,” “Isla Vista,” “radio silence, WENZ, WJMO, Cleveland,” and a personal favorite, “queerer weather.” A brief, pithy, prodigious aside—just listen:

________They think we

and our kind will usher in a new era

which could be called The Tyranny

of Choice, and then their grandchildren

will marry dogs or potted plants and there goes

the family tree, so to speak. The language

of fear is magnetic and simple, easily digested

and attracted to itself.

There is also a series of examinations of white privilege that are profound, painful, and unflinching: “white girl interrogates her unreliable memory of certain eras,” “white girl interrogates her recurring dreams,” “white girl interrogates the Oklahoma bill banning the wearing of hoodies,” and “white girl interrogates her own heart again.” Whatever else you’re searching for, you’ll stop at each of these essential intersections, idle without idling.

Perhaps you’re looking for images that show-without-telling, circumvent the cerebral in favor of the visceral? Perhaps you’re listening for surprising swerves of language—where “gentle” becomes a verb, where “mortuary” becomes an adjective, where “horror” and “gorgeous” hinge together on a hyphen of unexpected power?

Here:

________the giant white dog

gentling against the blue

house

And here:

________The sun’s a gun in the maw

of the planet, all of us clocks now

showing how late late the hour,

how horror-gorgeous.

And here:

________hollering warning

across the dark unlistening water as if

we were not, even then, a mortuary shore.

Or perhaps you’re a teacher looking for a prompt, an engaging starter line to set your students writing? Look no further than this one: In the photograph I do not have of us…Then, look further. McConnell’s book reverberates with invitations to make responsive art. Even when you don’t see the ellipses, trust that they are there.

Now, again:

The truth is, I don’t know how to end this either. I love the way McConnell’s poems are neither raw nor refined but always in-between—reckoning. That’s even the title of one such poem and the best description I can offer of this poet’s overarching aesthetic. Her poems move—speed up, slow down, circle back, swerve—and the engine that drives them all the way through this book is a precise, vigilant, and fearless commitment to reckon.

I thought I might end with these lines. They seem like strong review-ending lines: “We love who we can love, and the rest/stay ghosts.”

Or maybe these: “Once/We were monsters. Once we were/human. Once we flew.”

Better still, I thought—these:

________Studying the leaves

on the topmost branches on the tree at the end

of the world. We know what we did

to get here. We’re still living in these mouths.

Then, I remembered a line I jotted down in my notebook—a line that felt especially resonant for me, reading this book surrounded by family who are not my first family, who are family nonetheless: “I don’t know what I’m supposed to do about the lost,” McConnell’s speaker confesses. Does anyone? I wonder.

Last: While I was staying with my Outlaws, Christmas cards arrived every day in the mail. They were usually pictures of the senders’ families—the whole family or just the children, sometimes with family pets and sometimes without them. I enjoyed looking at these people, even though I didn’t know them. I wish I could explain.

On the last day of our visit, a card came from a family my Outlaws didn’t know. It was addressed to the previous residents of their home, people who had long since moved away. The card read Happiest Holidays in gold script, accompanied by a picture of mom, dad, girl, boy, and baby. Beneath them, a simple row of names: Morgan, Chris, Clara, Wilson, and Greta. Everyone hopeful, it seemed. Everyone smiling.

As my brother-in-law tossed the card toward the recycling bin, I intercepted him. I wish I could explain. It’s true—I didn’t know these people any more than he did, but I wasn’t ready to let them go. I didn’t know them, but I decided to hold onto their names and faces just the same.

As we were leaving town, I tucked that card inside my copy of when they say you can’t go home again, what they mean is you were never there, forgetting all about it on the thousand-mile drive. But when I opened the book today, another uncanny: the card was poking up from a poem called “disasterology: how to survive the apocalypse.” I studied their faces again—Morgan, Chris, Clara, Wilson, and Greta—and felt a flush of goodwill toward them, a flurry of compassion—as though they were my family after all. Then, I read the poem’s last lines, which I can picture in gold script at the top of a future Christmas card:

________If distance is a myth and we

are neighbors, or the same creature with multiple

faces, breathing the common, unspeakable air

which has us in pieces, I’m nothing

without you. Don’t say it’s too late to try.

when they say you can’t go home again, what they mean is you were never there

By Marty McConnell

Southern Indiana Review Press

Paperback, 9781930508422, 88 pp.

December 2018