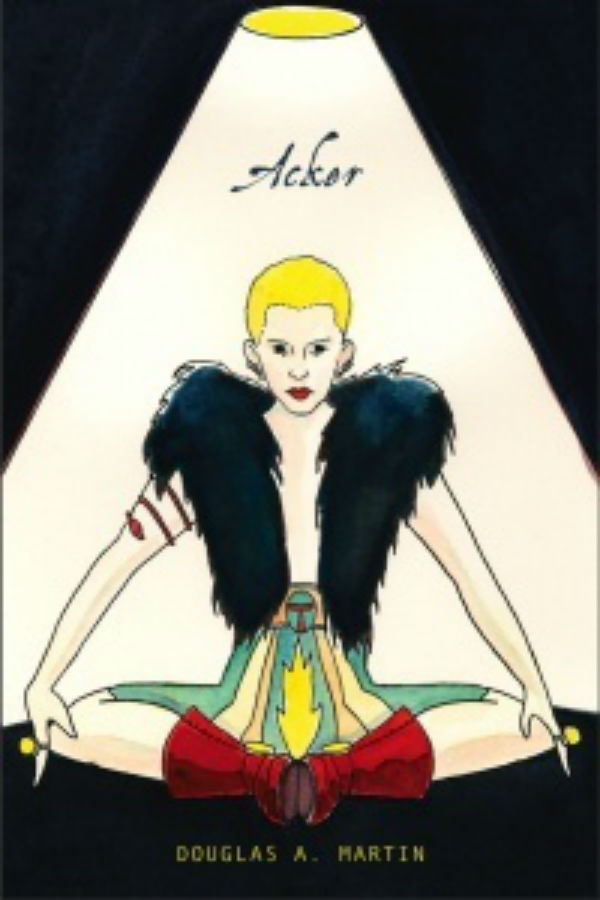

‘Acker’ by Douglas A. Martin

Author: Daphne Sidor

January 2, 2018

“My author,” Douglas A. Martin calls Kathy Acker in this book-length essay, as if she had invented him. Martin is too tentative and cerebral a character to really resemble one of Acker’s protagonists, those hothouse hybrids of classic literature and pulp libido. Still, it’s easy to guess how her career might have opened up the spaces Martin’s writing has explored. There’s the refusal to color within the confines of genre. There’s the pirating of real-life literary figures, like the Branwell Brontë of Martin’s novel Branwell. And surely Acker wouldn’t have resisted the opportunity to turn a rock-star romance into literature, as with Martin’s Outline of My Lover, acknowledged to be based on the author’s relationship with Michael Stipe.

Now, Martin turns to consider Acker directly—or perhaps not quite directly. She is a slippery subject: a bisexual feminist who filled volumes with a self-obliterating desire for men; a woman who immersed herself in old books while donning highly visible outward identities as a stripper, punk, bodybuilder. If her work was in one sense frankly autobiographical, it was biography refracted into a hundred distorting variations. Martin begins by noting that facts as basic as her date and place of birth can’t quite be pinned down.

“Put two different I’s on a page side by side. Then put yourself in a parenthesis among them. Then go ahead. Put more,” Martin writes in summary of Acker’s approach to the first person. By multiplying and blurring her narrators she constructed a sort of pummeling wall of sound, which often felt nearer to music or visual art than to anything else happening on a page.

Martin’s voice does not much resemble Acker’s, but he is equally committed to warping language to suit his needs. “A complete picture, or holes in the story, holds evolve back-and-forth between passages of utterance, comprised of what she writes in novel patches and scripts of criticism along in interviews”—should one start diagramming sentences like these, or simply let them slide past like poetry?

But such inelegance is a strategy. Elsewhere, he explains:

When I put down a word that cuts against the ingrained, or that goes both ways, the compass of bearings turns. You need to stop and stay, relax a while, look around rather than getting on to that next explicit, “real” action.

For some readers, all this verbal friction may serve more as an irritant than an invitation to meditate. Certainly, newcomers seeking a brisk, accessible introduction to Acker should turn elsewhere. (Chris Kraus’s recent After Kathy Acker may prove useful.)

Martin has other concerns. He puzzles over his author’s rightful place among genres and lines of influence; he plays with the algebra of matching figures in Acker’s text to figures in her life. When he supplies context it’s intimate, if not insular, and his treatment of Acker’s contemporaries is animated by the sense that he’s just barely missed out on a scene he’d like to have joined. (One thread even involves Martin’s rejection from a symposium on Acker’s work.) “In a document like this one, I do simultaneously perpetuate and fetishize the cachet of an increasingly dated milieu,” he admits.

It’s arresting, when Martin allows his emotional motivations to break through like this. One flickering presence in Acker is Martin’s mother, “also now AWOL,” he interjects suddenly amid a consideration of Acker’s mother, who abandoned her daughter first emotionally and then literally, by suicide. In one lyrical late passage he recalls visiting an exhibition of items from Acker’s wardrobe and being overwhelmed by childhood memories: “I walked up under the garments hanging, being dominated again by them, being a boy on the floor of my mother’s wardrobe to hide, in trying to also be included.”

To hide, in trying to also be included: that’s an apt description of many a reader or critic’s secret task, insinuating oneself into a beloved text until it seems to contain and compensate for one’s own loves and struggles. In the work of Acker and her devotee Martin, this process is—well, perhaps not entirely laid bare; laying bare is not what they are about. But acknowledged, honored, embraced.

Acker

By Douglas A. Martin

Nightboat Books

Paperback, 9781937658717, 264 pp.

October 2017