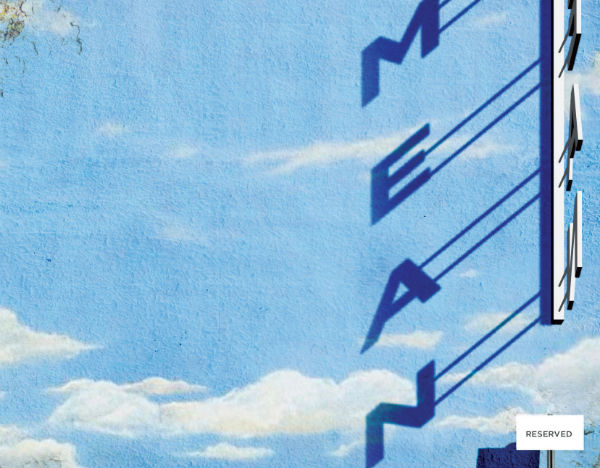

‘Mean’ by Myriam Gurba

Author: Liz von Klemperer

December 21, 2017

Myriam Gurba’s memoir Mean is an exploration of girlhood, and the violence that lurks in its midst. The book chronicles Gurba’s sexual assault as well as her coming of age as a queer, mixed-race Chicana growing up in Southern California. Gurba approaches these topics with ample doses of dark humor, and I found myself both laughing and cringing from page to page. Gurba’s experience as a spoken word poet shines through in her colloquial quips and clever turns of phrase. It’s not an easy feat to inject wit into such a heavy subject matter, but Gurba does so with tact.

Although Gurba is the book’s protagonist, Mean is also dominated by the presence of Sophia Castro Torres, a migrant worker who was raped and murdered on a baseball diamond in Santa Maria park near Gurba’s childhood home. Gurba’s story is in part one of survivor’s guilt, as the same man assaulted her the summer after her first year of college. Torres appears throughout the book like a ghost as Gurba deals with her own PTSD and sexual assault trauma. Mean is an ode to Torres, a retelling of a life and death that was minimized. In this sense, the book’s title acts as a double entendre, as it not only references ill temperament but also points to a desire to convey, to signify. Gurba’s mission is not only to tell her story but also to give meaning to a story that was sorely misrepresented and underreported by the media. Mean begins with a play-by-play of the night Torres died, and ends with a reflection on her life and death.

Mean is also a field guide for how to exist in the hetero patriarchy, and meanness plays a critical role in this navigation. For Gurba, meanness is a defense mechanism, a way to operate in a world that so often alienates and harms. “Being mean makes us feel alive,” Gurba writes. “It’s fun and exciting. Sometimes it keeps us alive.” Meanness is also an empowering celebration of girlhood. When Gurba and her friends play hooky in high school, for example, meanness manifests in their flippancy and blatant disregard for rules and authority. As Gurba and her friends drive and smoke weed out of a car window, she comments that “adrenaline and female bonding can overwhelm almost anything.”

Gurba subverts the trope of the “mean girl,” which has played a significant role in recent popular culture. The cult classic film Mean Girls, for example, portrays girls as catty. Their meanness is a result of their own insecurities and narcissism. Gurba offers an alternative narrative in which meanness, hardness, and bluntness are valid and valuable responses to patriarchy, oppression, and violence. Victims are not portrayed as weak or helpless. They are fierce, and sometimes they are cruel. Gurba is unapologetic when she looks back on bullying kids on the playground: “We act mean to defend our clubs and institutions,” she writes. Later she says, “being rude to men who deserve it is a holy mission.” Meanness is a way to dish back to the world what it doles out. Gurba draws an ultimate distinction, though, between different types of meanness, saying, “but I’m not so mean that I’ve ever raped anybody…that’s a special kind of mean.” She does not let us forget who the real offenders are. The title of the book in some ways acts as a tongue-in-cheek misnomer. Is her behavior really meanness, or is it a logical defense mechanism adopted out of necessity? Is it a way to gain power?

Meanness is alive in this book not only as a philosophy but also as a linguistic tactic that drives her work. The phrase “Somewhere on this planet, a man is touching a woman to death,” for example, is biting and brutal. There is no subtlety or euphemism here, only stark realities. In Mean, Gurba is offering readers an alternate take on victimization and trauma.

Mean

By Myriam Gurba

Coffee House Press

Paperback, 9871566894913, 160 pp.

November 2017