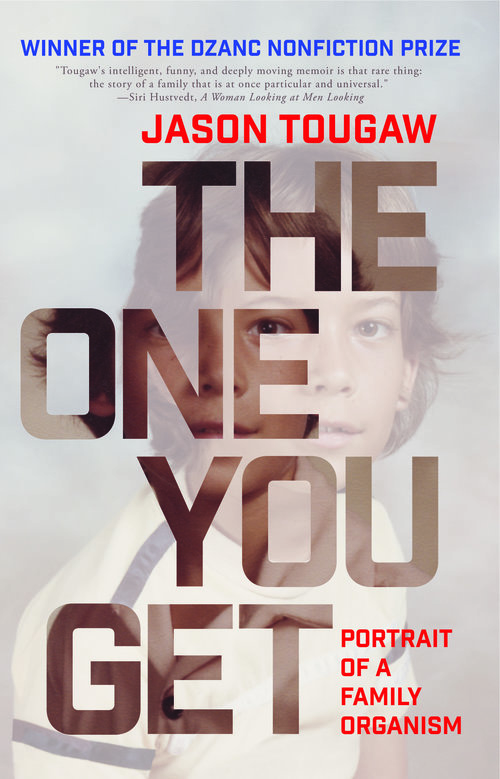

‘The One You Get’ by Jason Tougaw

Author: Alex Tunney

October 21, 2017

Anything can be altered: bodies, minds and stories. And they can be altered through various means: substances, other people, and the passage of time. Jason Tougaw is not only very aware of this, but also very curious about it. The memoir itself is a product of this curiosity.

“I have a plan,” he writes. “If I can master genetics and quantum physics—and then map the quantum leap of genes from Ralph’s bloodstream to Nanny’s—I will crack our family history wide open.” He knows his plan is ridiculous. In his attempt to comprehend the mysteries of his family, and ultimately something of humanity, he fails. However, he is more than successful in creating an illuminating work—a combination of a retelling and journey of discovery—calling it The One You Get.

There are two stories intertwining in this memoir. The first is the lore of the mélange of family members—the organism referenced in the subtitle—that Jason grew up with in seventies and eighties Southern California. The second is the older Jason, years and miles away in New York, investigating this past or, at least, this story using the lens of neuroscience and attempting to figure out not just the “how,” but also the “why” of his family and his life. Both versions of Jason are unreliable narrators, his younger self interpreting his world through a young person’s limited understanding of the world and his older self having forgotten or misremembered things and carrying some understandable biases, and the book is all the better for it.

He begins the story of his life with how easily he could have not been. Choosing to give birth to him, his mother gets married to his father, Charlie. The marriage is short lived, and Charlie becomes something of ghost, haunting around the perimeter of his life. His mother then is married to Stanley for a time, and the three of them attempt to live somewhat off the grid. Jason recounts that, during most of this time, Stanley was preoccupied with “making a man” out Jason. His mother eventually gets Jason into public school, where he is diagnosed with dyslexia.

Tougaw is great at capturing the somewhat hallucinatory existence of childhood of adolescence, where children are constantly learning, meeting new people, going new places and learning new “rules” about their world, with Jason’s situation amplifying this. Outside of a core group of family, people tend float around him (friends, stepfathers and others). These people are living somewhat off the grid, struggling with their bodies or partaking in a substance or two—each of which occasionally leads to relatively erratic behavior.

There’s a certain cultural wave that helps Jason form his teenage identity: New Wave. It is his take on rebellion, both against his parents’ hippiedom and the contemporary mainstream of the 80s. As a teenager, his sexuality moves from experimentation to an identity, but also comes with a fear of HIV and AIDS. Tougaw decides to end the story by jumping some years ahead with the death of his maternal grandparents and his first time ever reconnecting with Charlie. This point is not the chronological end of events recounted, nor is it the full story of his life, but is a marker of the end of family organism as it existed for those two decades.

Throughout the memoir is the history of mental health of Jason’s family. Starting with his maternal great grandfather, who Jason believes to have been schizophrenic, the family lore is that there is something in their Portuguese blood that makes them behave the way they do. In addition to schizophrenia, his family members have dealt with bipolar disorder, alcoholism and brain tumors. It is not hard to figure out why he’s driven to understand genetics and attempt to use it as a master key to his life’s mysteries.

Jason, the author version, regularly imparts his learnings of medical facts and neuroscience with the reader during key moments. The inclusion of this scientific information isn’t always as well woven and occasionally feels dropped in. However, the times when this shared information isn’t just appropriate, turn it into something transformative.

A great example of this begins with, “Here’s where I use neuroscience to get back at Stanley.” I hesitate to say this moment is “meta,“ as it’s not just a simple wink to the audience but him sharing a very human moment, one that shifts the book from being a passive retelling of family lore and conjured memories. He brings the reader into his New York City apartment, somewhere to the recent past of when he was writing a version of this book, and reflects on his immediate surrounds as his thoughts of Stanley fight for some of this mental space. During a discussion of cognitive signals and noise, he’d rather have him be the latter, but his brain insists.

The mention of neuroscience and other medical elements may make the tone of this book sound clinical, but Tougaw balances his critical eye and curiosity with compassion. Not just because it is about his family, but he shares a general warmth towards humanity and nature. He writes:

So we are always people without stories, imprisoned in core consciousness, interacting with the air we breathe, the sounds of trucks and birds, the feeling of the keyboard, the colors of summer sky and foliage—and most fundamentally, our sense of our own bodies, bounded in the instant. And we are always people with stories, people who live with others, exchanging impressions, building memories, becoming each other’s “objects.” And the objects, remember, make us who we are. […] We are each other’s objects, and we build each other.

Again, anything can be altered.

Tougaw has captured the contradictions and changes of his childhood, a specific period when parts of the family organism reacted strongly with and against each other and the outside world, and filtered it through his own recollections. It’s a mix of research, lore and memory. It’s something great made from what he got.

The One You Get: Portrait of a Family Organism

By Jason Tougaw

Dzanc Books

Paperback, 9781945814327, 320 pp.

September 2017