“What if I risk/Taking the head of death/Here in the dark, far/And deep”: Jericho Brown Adds Risky, Prophetic Poems to His Evolving, Elegiac Canon

Author: Julie Marie Wade

December 3, 2014

Recently, I’ve been toying with the idea of a graduate seminar devoted to the study of writers’ early work, in particular their second books. I wonder: wouldn’t it be helpful and ultimately galvanizing to read the first and second collections by a small group of writers and then to explore the kinds of leaps and recursions each writer makes between the debut and the sophomore volume? It’s the kind of class I know I would have benefited from as a student who was determined to write multiple books in her career, and it’s certainly the kind of class I would like to offer now as a teacher, invested as I am in my own students’ close reading and emulation of other writers’ work.

When I begin to craft my hypothetical syllabus, there is no question as to the first pair of books I will choose: Please (New Issues Press, 2008) and The New Testament (Copper Canyon Press, 2014) by Jericho Brown. Even their titles suggest a shift in tone, a progression from supplication toward avowal. I hear in them the difference between an entreaty and a demand.

Please: as in a formal or polite request, e.g. Please listen; as in an offering, even a sacrifice, made to satisfy another, e.g. May it please you. Remember how that first extraordinary collection begins: our speaker turning outward to address the self in second person; our speaker lingering beneath the low lights of the phantasmal nightclub; our speaker confiding, “You can’t tell/The difference between a leather belt and a lover’s/tongue. A lover’s tongue might call you bitch,/A term of endearment where you come from, a kind/Of compliment preceded by the word sing.”

The New Testament from this speaker is an act of testimony; a statement of possession, e.g. a last will and testament that attests “a dying man//Must have a point.” This speaker possesses himself and his life more completely now, faced with a different kind of threat. There’s still that leather belt in the background—that sting of past violence and betrayal, but there is also this present battle looming: “My doctor clings to the metaphor//Of war. It’s always the virus/That attacks and the cells that fight or die//Fighting.”

Our speaker addresses us from the first page of this extraordinary second book in first person—from the “Colosseum” no less, a place where brave men, or men made brave by circumstance, fight for their lives. “I don’t remember how I hurt myself,” he begins, “The pain mine/Long enough for me/To lose the wound that invented it.” By the end of this poem, he declares himself “what the gladiators call/A man in love—love/Being any reminder we survived.”

In my imagined class, I ask my students: “How are these two books connected? In what ways is The New Testament a continuation of Please; in what ways is it a departure?” One of my students might say, “There’s that moment in the new book where the speaker tells us, ‘I thought I’d be bored with men/And music by now’—which of course he isn’t—but I hear in that line a tangible touchback to Please, with its series of poems as musical tracks and its series of poems titled with men’s first names.”

Another student might follow: “It’s all here, you know—the self in relation to music, to longing, to the Bible—the self in relation to all these different models of truth, and also, the self in relation to the past. But there’s a new kind of authority over experience in The New Testament, and with it comes a new kind of clarity, like when the speaker says, ‘We breathe until we don’t./Every last word is contagious.’ That closing couplet gave me chills.”

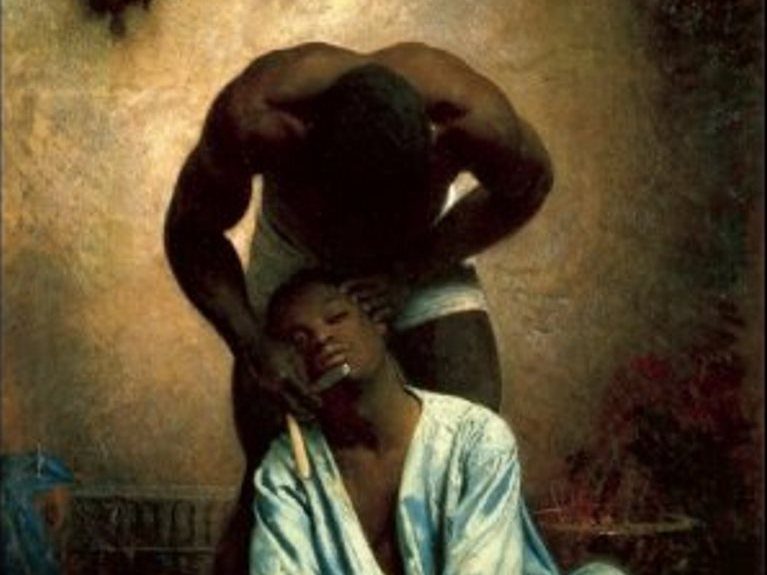

After a while, we might turn to an early poem of Brown’s that I often use in class to discuss the challenges of writing formative experiences, particularly traumatic ones. The poem is “Detailing the Nape” from the first section of Please. Our speaker begins, “It’s our first summer at Grandmother’s, and after our showers,/she inspects the dark condition of my sister’s neck, declaring it/filthy.” The speaker “peek[s] through a cracked bathroom door,” as the grandmother scrubs the sister’s neck “as religiously as she scours the toilet each Saturday.” Torn between reverence for his grandmother’s authority and compassion for his sister’s plight, the speaker is silent for a long stanza, a witness frozen at the threshold. Finally, moved by his “sister’s distress,” he “open[s] the door wide” and pronounces, in what I imagine to be a quavering tone, “M’dea, I think/that’s blood.”

In Please, our speaker is breaking silences, finding and claiming his voice. In The New Testament, he is exploring anew the range and depth of his song. We might consider how this speaker sings of the past in a new poem like “Labor.” Though this poem explicitly describes Saturdays spent “cutting grass for women/Kind enough to say they couldn’t tell the damned/ Difference between their mowed lawns/And their vacuumed carpets,” its culmination addresses the poet and thus surpasses these expectations of service and submission. He could even be writing to a former self, young and small, who once hesitated in a doorway: “I don’t do that kind of work anymore,” this new man says. “My job/Is to look at the childhood I hated and say/I once had something to do with my hands.”

In my imagined class, we will no doubt speak of Brown as image-maker and as elegist—two defining aspects of his identity as poet. We will consider the recurrence of fire, the struggle over names and the politics of naming, even the appearance and reappearance of a man called Derrick. In Please, he is “Derrick Anything But;” he is “Derrick of the gorgeous/Gold teeth, […] Derrick sweaty hands. Derrick baby grand.” Derrick is music and a man among men. We will notice how the speaker names Derrick but does not name himself in relation to Derrick. But in the new book, our speaker revisits the past in order to transmute ambiguity into certainty, and the power of suggestion into the power of decree: “When you measure the distance/Between this grave and what I gave, you’ll find me//Here at the end of my body and in love/With Derrick Franklin.” It is a full name this time. It is an unequivocal declaration of love.

In an early poem in The New Testament called “Heartland,” the speaker riddles his readers with the following assertion: “This is the book of three/Diseases.” I will ask my imagined class, “What do you think they are, these three diseases?” and then, inevitably, I will ponder my own response to the question at hand.

In the poem that precedes “Heartland,” our speaker discloses, “in my 23rd year,/A certain obsession overtook/My body, or I should say,/I let a man touch me until I bled,/Until my blood met his hunger/And so was changed, was given/A new name.” Though HIV is the most literal of the three diseases Brown’s collection explores, his speaker describes contracting the virus in spiritual rather than scientific terms. This is not a matter of infection, we are to understand, but a matter of anointing, by which his body becomes a “[d]ear dying sacrifice.”

The second disease? It must be grief. How could it be anything else but grief for a speaker with three songs titled “Another Elegy”? There are many deaths mourned by this man, but the death of his brother is greatest among them: “Police responding to//Gunshots found Messiah// Demery, 27, shot once in the chest/Trying to rob Rodrigus//And Shamicheal.” How do you save a man whose name means savior? How do you accept that a savior could not be saved?

Later, our speaker is asked, “So, you don’t/Have a brother?” He contemplates his answer: “The next/Day to my students I’ll say, No, I don’t have a brother/In the world. His grief endures as a great affliction, and as another disease for which there is no cure. Those who suffer grief also endure guilt and doubt: “We thought your brother was dead…” the speaker cross-examines himself. “He is.//And his death made you/Visible?//You only see me/When I carry a man on my back.//But you arrived alone. That wasn’t me.//That was the man who lost/My brother.”

And the third disease? It is the disease of “Nobody in this nation feels safe, and I’m still a reason why;” of “nobody named Security ever believes me;” of “Police don’t ever show until/A bullet does some damage.” The reader might recognize and respond, That’s racism. Our speaker examines many symptoms of this cultural malady. Profiling is a symptom we might recognize: “Confiscated—//My Atripla. My Celexa. My Cortisone. My Klonopin. My/ Flexeril. My Zyrtec. My Nasarel. My Percocet. My Ambien.” Yet, there are other symptoms, too.

Of the past, our speaker writes, “In that world, I was a black man.” On the present, he laments: “Now, the bridge burns and I/Am as absent as what fire/Leaves behind […] Who cares what color I was?” Here, the speaker is addressing the comorbidity of racial prejudice and post-racialism. The same man whose pills were confiscated because of widespread prejudice toward black people is then denied the agency to claim his identity because post-racial rhetoric insists, “black is,/After all, the absence of color.” This is the ultimate double bind. Our speaker lives in a world that cares tremendously “what color [he] [i]s,” but only for the purpose of incrimination. What of racial pride? What of the power of community? This speaker declares, “I thought we ran/To win the race. My children swear/We ran to end it.” The post-racial claim I don’t see color is finally, in this speaker’s analysis, as infectious a viewpoint as that which ranks human worth by color.

“Something keeps trying, but I’m not killed yet,” The New Testament speaker proclaims. This “something” is multivalent. It is HIV, grief and racism. These are all, he reminds us, threats to our shared humanity. They are that which will kill us if they don’t make us stronger. The old leather belt is there, too, in the background. Its legacy of violence and pain is not forgotten. In the first poem of Please, this speaker instructs himself: “Remember your father’s leather belt without shaking/Your head;” this is a chilling enjambment. In the last poem of The New Testament, he instructs us all: “Let that sting/Last and be transfigured.” So it does in this masterful sophomore effort.

The New Testament

By Jericho Brown

Copper Canyon Press

Paperback, 9781556594571, 69 pp.

September 2014