‘Barbara Gittings: Gay Pioneer’ by Tracy Baim

Author: Victoria Brownworth

August 9, 2015

I was a teenager when I first met Barbara Gittings. Not yet sixteen but already a precocious wannabe lesbian activist, I was coming of age in Philadelphia where Barbara Gittings had been protesting for lesbian and gay rights since before I was born, an open lesbian carrying a picket sign in front of Independence Hall on the Fourth of July. An iconoclast. A leader. A pioneer.

Barbara was tall and sturdy and always looked serious, but she had a ready laugh and was quick to outrage for anything that oppressed those she called “my people.” She favored embroidered blouses and corduroy pants and was devoted, utterly and implicitly, to lesbians and gay men and the cause of our equality.

Born in 1932 in Vienna, Austria, the daughter of a diplomat in the Foreign Service, Barbara was older than my parents and part of a wholly different civil rights movement than the black civil rights movement I had grown up with. My parents’ activism meant that I’d been raised in activism from infancy. By first grade, I knew who all the black leaders were. But I didn’t know when I met Barbara Gittings that she was the Rosa Parks of lesbian and gay rights.

The movement Barbara and her cohort of activists introduced me to was a movement I had never heard of until the early period post-Stonewall, when a local Philadelphia underground newspaper, The Distant Drummer, began running little stories on its back pages. It was there that my teenage lesbian self would discover radical lesbians and the Gay Activists Alliance. But first, I discovered the Homophile Action League (HAL) and its Philadelphia leadership—Byrna Aronson, Ada Bello, Rosalie Davies, and Barbara and her life partner, Kay Tobin Lahusen.

It’s difficult to articulate how disparate a time that was and how significant a change agent that Barbara Gittings would prove to be. In the era Barbara had come of age—the pre-Stonewall, pre-Internet, pre-fifty different ways to describe your orientation on Facebook era—there was just this vast wasteland of “Am I the only one?!” Into that blank, empty and scary space of not knowing how to connect with other people like you—other lesbians and gay men, other “homosexuals”—there came the pioneers. Barbara Gittings was one of those: a mother of a movement.

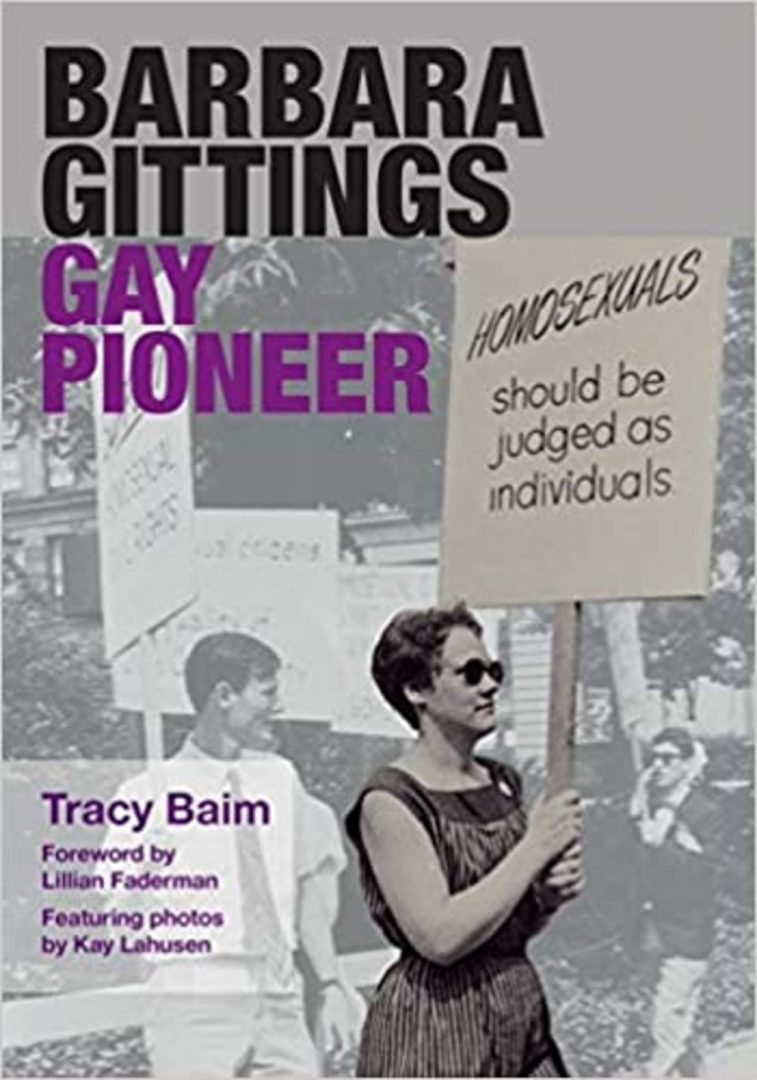

When I met Barbara, she’d already been protesting publicly for the rights of “homosexuals” since well before I was born. She’d been out in front of the Liberty Bell—one of the most public of spaces in Philadelphia in those years, swarmed with tourists every day of the week—in her sleeveless dress and short hair. She looked like somebody’s carpooling mom, except her sign read, “Homosexuals should be judged as individuals.” Where did she get the guts to do that?

How did she decide that it was time for lesbians and gay men to be treated with respect, dignity and equal rights under the law? What made her think, years before Stonewall, that she could openly declare herself lesbian in the 1950s at the height of the House Un-American Activities Committee witch hunts that targeted homosexuals. How could she parade around in public with a literal sign on her that said, “Equality for homosexuals”? What even made her think we deserved equality when everyone else called us “sick,” “perverse” and an “abomination”? Meeting Barbara Gittings when I was a teenager emboldened me to be a lesbian.

In the years post-Stonewall, at my all-girls high school, the dress code still demanded that we wear skirts. There was no gender nonconformity allowed. The closest you could get was a black turtleneck and black tights with your miniskirt. Yet, in the midst of all that straight-appearing, anti-feminist-yet-woman-centered, focus-on-college girls’ atmosphere of my academically excellent school, there was an undercurrent that I discovered almost immediately: lesbianism.

There were lesbians on the faculty who had been there when my mother had attended twenty years earlier—women she warned me to stay away from. There were lesbians in the student body, including the upper class woman who introduced me to lesbianism at a sleepover my freshman year. But no one mentioned the word lesbian, even as we passed purloined copies of ragged old Ann Bannon paperbacks from girl to girl. No one said what couldn’t be said: that for some of us, the kissing at sleepovers wasn’t going to be an adolescent phase, but a lifelong desire. I said it. Barbara Gittings said I could. She was there, at HAL, standing at the coming-out gate, explaining why we had to declare ourselves, burst from the closets and speak our truth—not just for ourselves, she would explain, but for “our people.”

In that girls-school atmosphere of simmering Sapphistry, I was the girl to break the silence and scandalize my family and the school by being the first to be expelled for being a lesbian and a “bad moral influence” on the hundreds of other girls. That experience at the tender age of not-quite-sixteen turned me into a lifelong activist, and Barbara Gittings was there at HAL, ready to be one of my role models.

When I met Barbara, it didn’t occur to me that this woman was older than my mother. Her lesbianism—her overt, blatant, walk-down-the-street-with-her-lover lesbianism—made her my peer, my sister, my comrade. We were in the same marginalized club. I saw her as someone whose activism I wanted to emulate. I saw her as a lifeline out of the heterosexual world that I knew, even then, was not and would never be my world. Barbara, with her no-nonsense approach and her single-minded purposefulness, was a beacon lighting the path to my lesbian activism.

Barbara was a keen role model for any activist. From the first time I met her until the last years of her life when I would run into her at Whole Foods or Giovanni’s Room Bookstore or just see her on the streets of Philadelphia’s gayborhood, always in her characteristic sneakers with her lavender backpack, she was the same: dogged, determined, forceful, a leader. But as a teenager, I had no idea how much Barbara had accomplished, how many risks she had taken, how hard and resistant the ground she broke was. What I did know, or intuit, was how utterly fearless she had seemed to be—and I knew I wanted to be just like that.

Tracy Baim has built her own lesbian legacy. Over the past thirty years, she’s run Chicago’s LGBT newspaper of record, Windy City Times, which she co-founded in 1985. In 1994, she was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame. In recent years Baim has concentrated on books about our LGBT history. Her Gay Press, Gay Power: The Growth of LGBT Community Newspapers in America was a finalist for the 2012 Lambda Literary Award. She’s also written a series of biographies about lesbian and gay activists: Leatherman: The Legend of Chuck Renslow, Jim Flint: The Boy From Peoria and Vernita Gray: From Woodstock to the White House. Barbara Gittings: Gay Pioneer is Baim’s latest.

Detailing the extraordinary activism of Gittings, Baim breaks her biography down into eight chapters. There’s an opening chapter on Gittings’ early life and a closing chapter on her final years. Another chapter details Gittings’ forty-six-year relationship with Kay Tobin Lahusen, who participated in this book and provided myriad incredible photographs, many of which are now archived in the Manuscripts and Archives Division at the New York Public Library, and which detail Barbara’s activism, the burgeoning gay liberation movement (when lesbians were not yet included in the name), the couple’s relationship, and the major events that occurred throughout the period of Gittings’ activism.

The other five chapters are each devoted to an aspect of Gittings’ activism, beginning with the 1950s and Gittings’ involvement with Daughters of Bilitis and its publication, The Ladder. This is intriguing because it is here that readers will see how impatient the twenty-something Gittings was for change. She was already out of the closet and ready to take on…well, everyone, when she joined DOB and worked her way into a leadership role.

Gittings believed that The Ladder, which was founded in 1956 and of which she became editor in 1963, should have been used to address the “experts” who defined homosexuality as a mental illness and who Gittings asserted were the foundation for anti-gay attitudes in society. A 1964 report from the New York Academy of Medicine had called homosexuality a “preventable and treatable illness.” Gittings queried that presumption by the NYAM, writing, “It’s a reminder of the sly, desperate trend to enforce conformity by a ‘sick’ label for anything deviant.”

In her foreword, Lillian Faderman notes that Gittings wrote to the NYAM on The Ladder’s stationery, challenging them on their labeling of homosexuality, and that this was the first time anyone had done so. Gittings’ letter was reprinted in The Ladder. Yet, her relationship with DOB became strained. Not everyone was ready to exit the closet, Stonewall was still years away, and millions of lesbians lived in the hinterlands. Even Philadelphia, then the nation’s fourth largest city and a mere ninety miles from New York City, wasn’t ready for the shift in consciousness that Gittings was calling for.

Baim’s next chapter takes us through Gittings’ protest years. She’d become close friends with Frank Kameny, with whom she was picketing and protesting everywhere: Philadelphia, New York, Washington, D.C. The two of them would lead actions against the Defense Department and the Civil Service Commission. Gittings would be out in her flowered dresses picketing the White House, the United Nations and Independence Hall.

Yet, as extraordinary as those actions were, it is in Baim’s fourth chapter where Gittings takes on the American Psychiatric Association. This is unquestionably the most pivotal chapter in Baim’s book and the one that everyone must read.

When I say that as a young child I knew who all the black civil rights leaders were, from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to Stokely Carmichael, I did. Those names were always part of the parlance of my household growing up; some, I was fortunate enough to even meet. But when I met Barbara, I had no way of knowing what a remarkable figure she was, because our lesbian and gay history was not being recorded the way the black civil rights movement’s history was. That Barbara was as important to our burgeoning lesbian and gay movement as those key black men and women were to theirs remained unknown to me until years later. Even though I knew Gittings, I didn’t know how much she had already done to pave the way for other activists, and for the lesbian and gay man in the street, as it were. That letter Gittings wrote back before Stonewall rankled. She was determined to tear the sickness label off every lesbian and gay man in America.

And, well, she did. You will have to read the actual chapter for the complex details, but Gittings took on the American Psychiatric Association and the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), which had determined that homosexuality was a mental illness. By the time she was done, the DSM had been changed and lesbians and gay men were no longer—officially at least—considered mentally ill. The story of how she began the public part of the fight she’d been waging behind the scenes for a decade, by buying a booth at the APA convention in 1972 with the banner “Gay, Proud, and Healthy: The Homosexual Community Speaks,” is just extraordinary.

Gittings also managed to get herself and Kameny on a panel about homosexuality at the 1972 convention. She also found herself a gay psychiatrist to even out the panel that also included two heterosexual psychiatrists. It wasn’t until reading Baim’s book that I discovered that the psychiatrist Gittings found, who appeared in disguise, was Dr. John Fryer, a frequent guest at my parents’ house. All those years, there had been a gay man—the “bachelor” my mother invited for single women—at our dinner table, and I didn’t know. (There are amazing photographs of this APA event in the book; the disguise is a heavy plastic mask.) That was the era of the closet. That was the era Gittings was determined to end.

Chapters on Gittings’ protests at the American Library Association and her work getting lesbian and gay issues in front of the news cameras round out the activist chapters of the book. The ALA, which once asked who “those people” led by Gittings were, and who were getting all the media attention, now has a literary award in her name. Gay Pioneer presents a full portrait of an activist’s life, both public and private. Lahusen’s dozens of extraordinary photographs provide a visual trajectory of Gittings’ life of dedicated service to lesbians and gay men and our equality.

A year or so before her death from breast cancer, I saw Barbara at the annual lesbian and gay film festival in Philadelphia. She suddenly looked like an old woman to me, her hair now white and sparse from the treatments, but she wore one of her characteristic embroidered blouses and there was no hint of frailness about her. We talked breast cancer (she knew I was a survivor), and we talked lesbian activism, and then we went to our respective seats, the lights dimming. It would be the last time I saw her. She died February 18, 2007 at age seventy-four.

Gittings described her life of activism this way, in 1999: “As a teenager, I had to struggle alone to learn about myself and what it meant to be gay. Now, for forty-eight years, I’ve had the satisfaction of working with other gay people all across the country to get the bigots off our backs, to oil the closet door hinges, to change prejudiced hearts and minds, and to show that gay love is good for us and for the rest of the world, too. It’s hard work—but it’s vital, and it’s gratifying, and it’s often fun!”

Kameny called her the mother of the movement, and she was definitely that: an omnipresent activist who fought her entire life so that her people could be themselves in the sunlight. I was honored to have known such an ardent activist and to have been under her tutelage as a young lesbian. Baim’s book introduces this stalwart activist to a broad audience, and Gittings’ determination, achievement and love for her community shines through. We have much to learn from her life of activism, not least of which is why we cannot give up the fight.

Barbara Gittings: Gay Pioneer

By Tracy Baim with Kay Lahusen (Photographer), and Lillian Faderman (Foreword)

CreateSpace

Paperback, 9781512019742, 236 pp.

June 2015