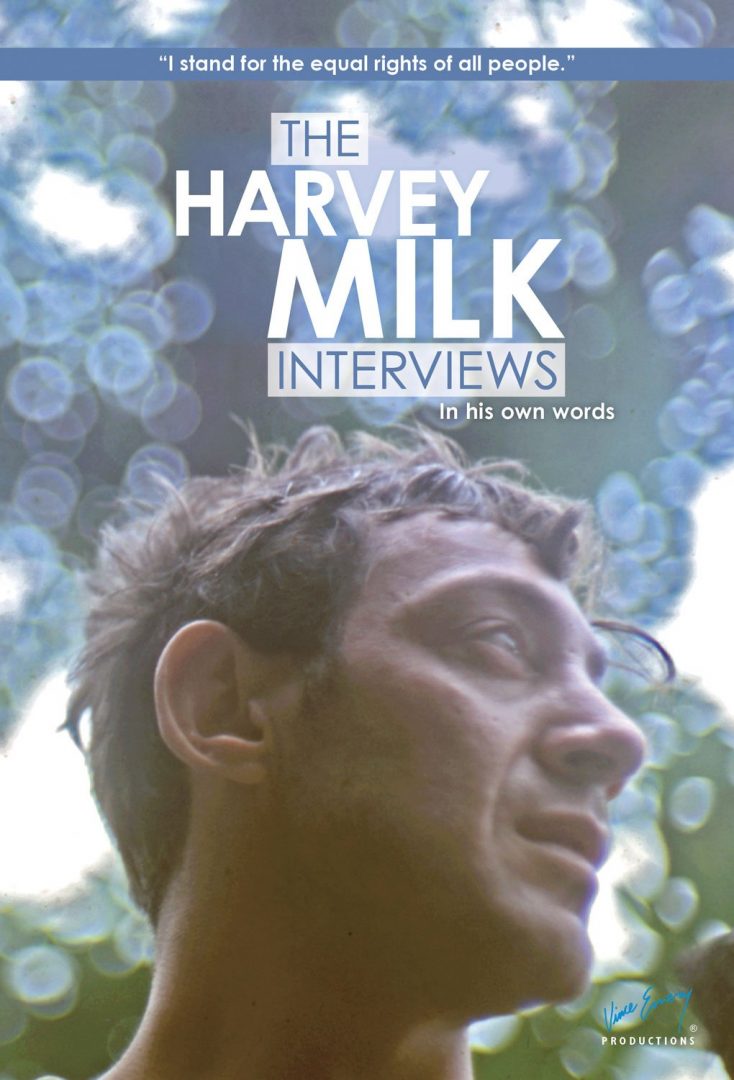

‘The Harvey Milk Interviews: In His Own Words’ edited by Vince Emery

Author: Tom Eubanks

August 5, 2012

With the publication of The Harvey Milk Interviews, editor Vince Emery humanizes the slain politician, allowing Milk’s own words to temper the hagiography advanced by Randy Shilts’s The Mayor Of Castro Street, as well as the subsequent documentary that brought Milk to a wider audience. At the same time, Emery’s research provides enough evidence to affirm Milk’s canonization by the Hollywood trinity of Gus Van Sant, Dustin Lance Black, and Sean Penn.

In 1977, I was one of those pre-gay formative kids who got a blast of homosexuality (and all its evils) from the three networks, compliments of born-again orange juice pusher Anita Bryant. Her national campaign to repeal a Dade County anti-discrimination law didn’t teach me anything about morality. It didn’t bring me closer to Christ, or orange juice. It certainly didn’t put Florida in a positive light (a trend that continues to this day). But it did nudge me ever-so-gently toward my own truth. Thanks to Anita Bryant, I came to know who I was. Through her ignorance, I came to learn there were enough people like me out there to be considered a community and a threat. In an interview with Tom Hayden for the Center for Economic Democracy (CED), published March 22, 1978, Harvey Milk foresaw the lavender lining in Bryant’s storm clouds, calling her “the best thing for the gay movement.” He went on to explain:

Every household talked it about it—they’d scream at the TV, “You f—ing faggots! But that’s the opening of dialogue. Before, they never would have even said that. She did to the gay community what Richard Nixon did to a lot of people. A lot of people realized what’s happening.

Bryant’s success in Florida also prompted California State Senator John Briggs to go after gay teachers in his state by trying to implement Proposition 6, aka the Briggs Initiative. Shortly after his lover, Jack Lira, hung himself, Milk engaged in a series of searing debates with Briggs over Prop 6. Angry, intelligent, and wickedly funny, Milk comes to glorious life in his three encounters with the senator.

The first, at the New San Remo Restaurant, was originally broadcast in an edited half-hour version on KPIX-TV. The program has been lost to history, but Emery reprints excerpts in which Milk’s words soar. In the second debate, captured by “an inexpensive cassette recorder in a crowded gymnasium,” Milk eviscerates Briggs. His five-minute rebuttal to Briggs’ opening statement and, following sustained audience applause, his own ten-minute presentation, take apart every phony moral and faux-Christian argument the right wing has wielded against gay people throughout the centuries. Milk’s eloquent words should be memorized by anyone who needs ammunition at hetero-political family gatherings. They also made me laugh out loud.

The third debate between Briggs and Milk was in Orange County, sponsored by the Pro-Family Coalition. The crowd response shows clear allegiance to Briggs’s small-minded ramblings. Yet, Milk fought back just as hard, and as humorously, as he had on friendlier territory. “Please—let ‘em yell,” he repeated at one point. He relished preaching to disparate choirs. Moments like these show how fearless and honest Harvey Milk was.

The early interviews take place during the years in which Milk lost a string of elections. They show his transformation from activist to politician to the leader he came to be. During this time he learned how to gain the trust of the “Archie Bunkers” of the construction trade unions, the hippies of the Haight, and large contingents of minority neighborhoods alike.

On June 7, 1977, when Bryant’s Dade County repeal succeeded, a near-riot erupted on Castro Street. The police knew that only one man could quell the massive crowd. Writes Emery, “Milk was the only person trusted by both the angry gays on the street and the police.” He was also the rare candidate who could garner endorsements from the liberal Bay Guardian and the conservative San Francisco Chronicle. According to Calvin Welch, who interviewed Milk for The Haight Ashbury Newspaper, “he was skilled at creating coalitions, and bringing people to a common view. There isn’t anyone who can do what he did in San Francisco politics now.”

Milk was finally elected Supervisor in November of 1977. Immediately, he unleashed upon City Hall what Vince Emery calls a “blizzard of legislative ideas” (wonkishly listed in a chronological appendix). The interviews that follow display a triumphant, if slightly power-mad, Milk in the national spotlight, fighting local issues (against real estate speculators and victimless crime laws; for pooper scoopers and Jane Jacobs-style urban planning), while quietly ignoring death threats and assuring young gay followers across the country that it gets better.

These collected interviews, articles, election questionnaires, and recorded debates show that Milk’s goal wasn’t merely to get people out of the closet, but, more importantly, as he challenged on KPFK’s This Way Out, “to get their checkbooks out of the closet!” He knew the power of the gay dollar even though he was quick to remind anyone that he had won office without any help from the (moneyed) gay machine. As he told Hayden in their CED interview: “I was sworn in on January 9 and on January 10 I had a fundraiser to pay off my campaign debt.”

While hyper-conscious of his importance as a role model for young emerging queers, he often told interviewers he wasn’t a gay politician, he was a politician who happened to be gay. Besides, as he told John Bryan of the Berkeley Barb: “Nobody can speak for the entire gay community—it’s too diverse.

Some people refer to Harvey Milk as “our Martin Luther King, Jr.” But The Harvey Milk Interviews shows Milk as a fiery, sometime arrogant, upstart leader, despised by the gay powers that be, and more concerned with solving the harsh economic realities of all marginalized groups rather than simply those with whom he shared a singular identity. Perhaps Milk was more like our Malcolm X.

But there are no comparisons among civil right heroes, only a pantheon for those individuals who not only succeeded on their own terms, but continue to change our world long after bullets took them from us.

The Harvey Milk Interviews: In His Own Words

Edited by Vince Emery

Vince Emery Productions

Hardcover,9780972589888, 360 pp.

April 2012