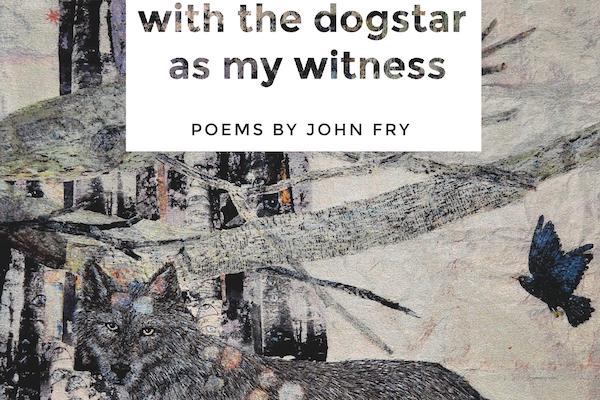

‘with the dogstar as my witness’ by John Fry

Author: Julie Marie Wade

July 11, 2019

When I finished reading John Fry’s debut collection with the dogstar as my witness, I promptly began to re-read it—but this time in reverse chronological order. The experience of reading this way was doubly illuminating, and I felt by the time I reached the first couplet of the opening poem “credo”—repositioned as last words—I recognized Fry’s invocation as a prophesy fulfilled: “like a preacher’s son returned to God—/but never the church—”

These words had become the dogstar itself, the brightest light in the book’s constellation. I traveled a long way by that dogstar’s light, only to find myself alive inside its central paradox at the end, sighing with a kind of ecstatic relief. Think when Eliot writes in The Four Quartets: “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” That’s how it was to read with the dogstar as my witness forward, then back. That’s how I’d encourage you to read it.

End

I’ve always appreciated the Notes sections at the end of certain poetry books, but Fry’s “Notes” crystallized for me something my favorite writers—of every genre—do. Fry writes, “Borrowed, echoed, remixed, or inverted, the following authors’ words walk beside my own.” Yes! I thought, sketching a huge asterisk that resembles a star (perhaps even a dogstar!) in my margin. I read not only to learn how a given writer is reckoning with experience but also to learn how a given writer is using other writers and artists—other thinkers and creators—as touchstones to inform that reckoning and its transmutation into art.

Now of course it doesn’t hurt that the ensemble of fellow pilgrims walking beside John Fry in this elegant, nuanced, and palimpsestual collection includes many of the same figures I turn to for guidance in my own reckonings. Members of Fry’s secular-spiritual company include Dan Beachy-Quick, Jean Valentine, Carolyn Forche, Fanny Howe, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Kerri Webster, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Kazim Ali, Emily Dickinson, Jane Cooper, Olena Kalytiak Davis, Louise Gluck, George Herbert, Mary Szybist, Flannery O’Connor, the Renaissance sculptor Donatello, and the Holy Bible, to which his speaker doggedly returns. This I understand as well.

What do we do with the texts that live deepest inside us, the texts that were chosen for us before we could seek our own companions? If we were raised within a particular religious tradition—within Christianity, let’s say, as Fry was, as I was—the words and concepts of that tradition comprise the first soundtrack to our lives. What if we still hear music there, despite the dogmas we can’t embrace? And what if we still hear music there, despite the dogmas that can’t embrace us?

The last thing I wrote after reading this book full circle—the first words that appear in my own messy pen-strokes on Fry’s verso page—are the “out” in “devout.” What I meant by them: Here is a speaker who has come out, only to be cast out, only to learn how to inhabit the space between “without” and “devout.” These are the poems of that habitation, that existence inside a liminal space. These poems model how to perch on the hyphen between “secular-spiritual” and not topple.

The last poem in the book, and the first in my re-reading, is called “every time you wish the sky was something happening to your heart.” (As Fry and I were both taught, The last shall be first, and the first shall be last, in the words of Christ.)

This poem begins:

as if it had something to do with

religion:

The antecedent isn’t unclear at all if you imagine a worldview where nothing exists that doesn’t have something to do with religion.

Then, the image upon which we are invited to feast our senses:

__________spirit in the wheel

of cattle egrets spun

out of the scorched field

lonely for livestock, eyes

of the alfalfa still asleep

below the saltpan moon

I know you see it, hear it, feel it—all that sibilance stirring you up: spirit, egrets (pluraled), spun, scorched, stock, sleep, salt. And the secondary consonance of the “l” harmonizing with that sibilance, too: lonely, live, twice in alfalfa, still, asleep, and salt. This music, with which religion may or may not have to do.

Then comes the em dash, one of so many in Fry’s collection:

—even if the gloaming wells up from this

While these dashes may serve in part as stylistic homage to fellow poet-pilgrim Emily Dickinson, they are also an extension of that implicit hyphen between the secular and spiritual. I think of Fry’s em dashes as tightropes the speaker is always walking across—the queer body in the queer-resistant tradition—poised, taut, controlled—trying desperately not to fall.

Then, the space opens up on the page. We see what is below the tightrope:

hallowed ground________I will not let thee go

Jacob’s pillow___________except thou

white feather ladder____bless me

The left side is religious in nature. We recognize these words and images from the Judeo-Christian tradition. Jacob dreams a ladder to Heaven, which symbolized his lineage as a descendant of Abraham, a man chosen by God. The ladder also symbolized the duties that accompanied this heritage.

The italicized words that harmonize with the un-italized words—God’s words speaking to Jacob—continue onto the last page of the collection, but with a switch in authorship. God, in other words, is not given the last word.

Instead, a vast white space appears between

white feather ladder____bless me

and what might be read as a free-standing epigraph on the adjacent page or simply an emergent worldview the speaker has chosen for himself.

I picture this speaker falling through the vast white space, but like a tightrope walker remembering he is also an acrobat, the speaker rights himself mid-fall and transforms the fall to flight. He lands gracefully on the words of George Oppen, newly consecrated, secularly divine:

I think there is no light in the world

but the worldAnd I think there is light

This may be Oppen’s way of saying, I don’t believe in an afterlife. I don’t believe in a ladder that leads to a holy place in the sky. But Fry’s title wish—that “the sky was something happening to your heart”—well, it’s come true in Oppen’s vision, hasn’t it? The world need not be a dark place unless there is a Heaven waiting beyond it. There is light here already. That light is real. That light is enough.

For every child who learned to “let [their] light shine” in the familiar Christian song; for every queer child who sang those words but learned to do the opposite—to “hide [their] light under a bushel”—this poem redeems that light and leaves the queer candle burning.

Middle

Whenever I read a collection of poems, I look for the fulcrum. While individual poems may have their voltas, the middle poem often serves—implicitly or deliberately (or both!)—as a volta in the book, a turning-point in the poet-speaker’s journey.

When you read a collection backwards, the fulcrum poem remains the same. It becomes a constant in the book—constant as the dogstar, we could say, this bi-directional volta, this poem that swings both ways.

There are three poems with the dogstar as my witness titled “debris field.” Three is the Biblical number for completion, which makes sense. The fulcrum “debris field” poem is the second of these, the middle one, which makes sense also.

Like any field, there is much open space here, little outcroppings of words arranged into clusters, separated by caesuras, which we might read as fallow land. (Nothing grows there now so something can grow there later…evidence of a cyclical rather than a hierarchical view.) There are also ampersands in Fry’s poem, the queerer way (I’ve always thought) of writing and. The poet doesn’t spell it out, but still he expresses it clearly—this compressed additive power that resists straight lines, that manifests as &.

This “debris field” begins:

before the world darkened

___________________________________you’d already

memorized the Alpha & Omega

Here in the middle poem, the poet-speaker invokes both beginnings and endings. The ampersand becomes the symbolic fulcrum between “Alpha” and “Omega.” The ampersand marks where we are standing now, fellow-pilgrims with our poet-speaker, out (or even out) in an open field.

He goes on to tell (diction) and show (spacing) the binaries of a queer Christian youth:

______________________________in your

beginning there was right

& there is

___________________wrong, all thatis clean

___________& what is not

of the Father

We may recognize the right/wrong, the clean/unclean paradigm from our own upbringings. We may hear the implicit because I said so of a parent, mortal or divine, refusing to be questioned, let alone defied.

Then, Fry names it, the passage that has become the bushel over so much queer light:

________________________just as he who lies

with a man as a woman shall

surely be put to death

—which seems implicitly another way of saying “be denied the light, the afterlife, the ladder to Heaven.”

At the end of the poem comes the essential turn of this collection. The poet-speaker, exiled in that field, sorting the “debris” of received language, separating, in his own way, the wheat from the chaff of all he has learned, reports back to us:

where such creatures are

_____________________________never spoken of

you

stalk across the steppes

I’m still thinking of Jacob’s ladder, but instead of rungs, there are “steppes” now, an intentional homophone with “steps.” Instead of ascent/descent, instead of the hierarchy of the ladder, there is the lateral expanse of this vast unforested grassland, these “steppes.” Instead of climbing, the speaker is free to roam, even to stalk. Where before he had learned only passive obedience, now he becomes an agent of his own desires, someone who “stalks” his own truth.

What follows, whichever way you’re reading, are the symbolic “steps” this speaker must take to clear his way clear in this clearing.

Beginning

The first poem in this book, which doubles as the last poem in re-reading, is called “credo.” It is a spiritual word meaning “I believe,” and it is also a secular word meaning “I believe.” How fitting that a journey should culminate with an assertion of belief! Fitting too, I think, to consider Fry’s “credo” as an ars poetica, his testament to what he believes a poem can do.

This poem is left-aligned and arranged in couplets. It is a poem of pre-fracture or post-fracture, full of tight, sonically resonant lines that portend or suture the breakage—and with it, the flung spaces—of other poems in this book.

At the perfect fulcrum of this poem, there is an asterisk that looks exactly like a star. Better put: there is a star posing as an asterisk. Six couplets above, six couplets below, a star at the center.

What does John Fry believe a poem can do? What makes this poem his meditation on the art of poetry? You can see it here in part of the first sequence of couplets:

___________________—since sky’s enamel lid slammed shut

I’ve looked for that angel unawares,

Prodigal or pilgrim, saint or sinner, to ask

Here is a poet committed to re-seeing, in both content and form, message and image. (That’s a credo, too, isn’t it? To believe in looking again?) I’m still thinking of that sky from the last poem that became the first poem. It’s an eye too, that sky, with an “enamel lid”—heavy, hard, a protective coating, almost like a tooth.

I feel certain I’ve never pictured the sky quite this way before, or conceived of a sky that slams shut. Does that mean darkness, condemnation, no afterlife? Does that mean, perhaps, no afterlife for you, our queer pilgrim—Hell as permanent exile from God, eternal banishment from light?

Here is a poet committed also to listening deeply, even re-hearing those first tracts of his life. The words angels unaware are Biblical in origin, invoking Hebrews 13:2: Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unaware. The first hearing is not to close the self off to anyone, for there may be angels in our midst, walking among us. The re-hearing is not to close the self off even to the self, even the self who may be cast as “prodigal,” cast as “sinner”—both euphemistic ways of saying “queer.”

After the star, which bisects the poem and marks its perfect volta, all the couplets turn to questions, yet there are no question marks. Here is a poet so committed to inquiry that asking is given, wondering is tacit. No special punctuation is required to signify the end of questions, for of course the questions have no ends. Fry thinks of Thomas, doubting. Fry thinks of Mary, crowning. Then, he thinks of Judas kissing Jesus—that epitomizing image/action of New Testament betrayal.

I’ve heard the story so many times. Judas identifies Christ—to the men who will put him to death—with, of all things, a kiss. A gesture of love that morphs into a gesture of betrayal. I’ve held this image in my mind for years, and now in five words, Fry makes me re-see it, then re-see everything: —did Christ kiss him back

With this final line, I’m sent reeling. The scene in the Garden at Gethsemane, referred to both as “The Kiss of Judas” and “The Betrayal of Christ,” has now been queered—vividly, viscerally. What if? I’m musing. What if Christ had kissed Judas back? What if that iconic betrayal of Christian doctrine could be re-seen, re-heard, re-questioned such that our primary associations with kissing—the pleasure, desire, love, and longing of it—could be restored?

John Fry is a poet committed to restoring, perhaps even restorying, what we are allowed to imagine, what we are permitted to believe—about others, yes, and also about ourselves. In lieu of answers, he offers insights. In lieu of imperatives, subjunctives. His invocations can be read as benedictions, his benedictions as invocations.

For me, this collection is akin to a queer anointing for any reader who has ever felt lost, cast out, unwelcome. Unlike the promises of evangelical traditions, this book won’t “find” you or “save” you. Instead, with the dogstar as my witness will acquaint you with the “wonders of the thicket” (another of my favorite Fry lines), will show you the beauty of all that is wide and open within you.

with the dogstar as my witness

By John Fry

Orison Books

Paperback, 9781949039207, 104 pp.

October 2018