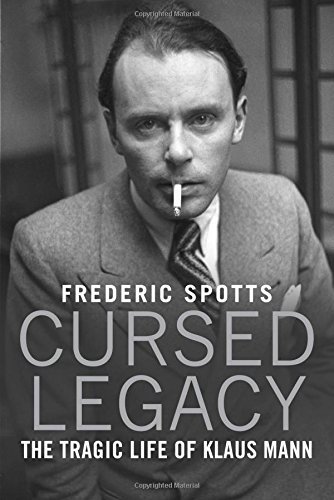

‘Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann’ by Frederic Spotts

Author: Walter Holland

June 12, 2016

Klaus Mann, son of Thomas Mann, author of Mephisto, was one of the first in Germany to write gay novels and plays. Not since reading Judith Thurman’s excellent biography of Colette some years back, have I been so captivated by a piece of writing and scholarship and the creative life and historical period it captures. The reverberations with our own contemporary times are uncanny and raise provocative questions about the role of the queer artist in society, especially a society faced with the lure of fascism and anti-liberal conservatism.

Klaus was an early foe of Nazism, writing against the wave of nationalism, xenophobia and racism that was sweeping across his beloved Germany. While his father Thomas and writers such as Alfred Döblin and Stefan Zweig vacillated in truly denouncing Hitler early on, Klaus felt compelled to leave Germany and to undertake establishing the anti-Nazi journal, “Die Sammlung” (“The Collection”).

As a result, Klaus was blacklisted and denounced as “a dangerous half-Jew,” his books were burned around Germany and his German citizenship was revoked. Thus began a life of amazing courage, tragedy and struggle. As a homosexual and a drug addict who suffered from paralyzing bouts of depression and insecurities fostered by the formidable shadow of his famous but aloof and critical father, Klaus became a driven, prolific writer of novels, plays, essays as well as an excellent journalist and public speaker. Moving to the U.S. with his father and their large family, Klaus taught himself English and adopted English as his primary written language. Like his dear sister Erika, Klaus denounced the German people for embracing Nazism and destroying as well as polluting the literary traditions of German literature. After the War he remained incredulous that anti-Nazification was largely ignored and supporters of Hitler were allowed to resume their professional roles in Germany.

A case in point was Gustaf Gründgens, the famous stage actor whom Klaus had an affair with prior to the War. Gründgens, a homosexual, remained in Germany and embraced Hitler and supported the regime. Göring saw him perform in Goethe’s “Faust, Part 1” as Mephistopheles and was so moved that he forgave the actor his earlier communist indiscretions as well as his homosexuality. In return Gründgens was appointed head of the Berlin State Theater. To keep up appearances the actor was forced to marry the actress Marianne Hoppe. While Klaus suffered as an émigré in anonymity, forgotten and despised, Grüngens’ career thrived even after the War with no repercussions.

Grüngens became the model for Hendrik Höfgen, Klaus’s main character in his most celebrated novel, Mephisto. The story is about an actor who must make the choice between political and moral integrity and political and professional opportunism during the Third Reich. In fact, it was the threat of retaliation by Gründgens after the War that delayed publication of the novel until 1981, well after Klaus’s death (even though it was first published in 1936 in Amsterdam but banned in Germany).

Wrongly accused of being a communist, turned down by publishers who in the isolationist days of America were not interested in the plight of Europeans, despised by Germans for having become an émigré and refusing to remain silent, and perpetually broke, Klaus struggled on. His sexual relations were erratic and unsatisfying for most of his life, although he longed for a long-term relationship. Fame as a writer was elusive. Poor timing and ill luck were a good part of his destiny.

Finally in 1949 in Cannes he was found dead in his room at the age of forty-two, ruled a suicide, although a thorough investigation was never undertaken. Here Spotts makes a compelling case to show the many reasons why suicide was probably not the case and that death was most likely caused by accidental poisoning with sleeping tablets (interacting with other drugs already in his system resulting in unintended toxic effects). To the end, Klaus was engaged in plans for a new book project and despite being in sizeable debt appeared ready for life’s ongoing battles.

In retrospect, Klaus Mann was a queer hero of the twentieth century to be admired, a gay man who acted upon his convictions, endured continual disappointment and only achieved the fame he so greatly desired after his death. Drawing freely from Klaus’s daily journal, Spotts gives us the internal psychological and intellectual trajectory of a troubled genius.

Prescient to the rise of Nazism and its dangers, Klaus was the first writer to sound the alarm and contemplate the unthinkable. While others laughed at Hitler and dismissed his early triumphs in 1932 with provincial elections, Klaus was quick to pronounce the results a “horrifying victory of lunacy.” When others accepted the claim “that democracy was ineffective and only dictatorship ‘gets things done,’” and that Hitler’s movement was “a perhaps imprudent but fundamentally sound and acceptable revolt against the ineffectiveness of ‘high politics,’” Klaus countered in a letter by stating: “As for myself I want to have nothing, nothing at all to do with this perverse kind of ‘radicalism.’ I cannot help preferring the slowness and uncertainty of the democratic process to the devastating swiftness of those dashing ‘counter-revolutionaries.’”

Klaus felt that passive acceptance of the “illusions of fascism would lead to ‘a new war and the downfall of European civilization.’” He refused to accept that Nazism represented a respectable “conservative revolution.”

No one could believe that Hitler would come to power “—a case of what Freud called ‘knowing and not knowing.’” Klaus Mann felt that the “German people [were] basically very intelligent” and would reject Hitler. His confidence was dashed in 1933 when Hitler became chancellor. He fled to Paris and revealed that “the essential reason for exile,” “. . .was that we were forced away by our own disgust, our horror and our forebodings.” Would that we could all draw our own lessons from this artist’s tragic life and act on our convictions in times of political turmoil.

Cursed Legacy: The Tragic Life of Klaus Mann

By Frederic Spotts

Yale University Press

Hardcover, 9780300218008, 352 pp.

April 2016