‘Stand by Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation’ by Jim Downs

Author: Jim Mitulski

June 1, 2016

The Stonewall Inn, already a New York City landmark, is likely to become the first national landmark to honor the LGBT movement for civil rights. Greenwich Village is full of locations significant to the Gay Liberation movement. One such is the former site just up the street of the Oscar Wilde Bookstore. More than a bookshop, it was an intellectual laboratory for this revolution. Its proprietor, Craig Rodwell, was an eccentric and principled philosopher/activist who deeply influenced the people and events that were essential to the changing social perception of homosexuality. His little bookshop at the intersection of Gay Street and Christopher Street fostered resistance and rebellion in ways both large and small. His passionate opposition to racism led him to formulate some of the early principles of gay liberation. And even his personal life would have far-reaching consequences. Rodwell undoubtedly influenced his ex-boyfriend, a conservative Wall Street businessman, who left New York for San Francisco, where he too embraced left-leaning politics and became the leader we revere as Harvey Milk.

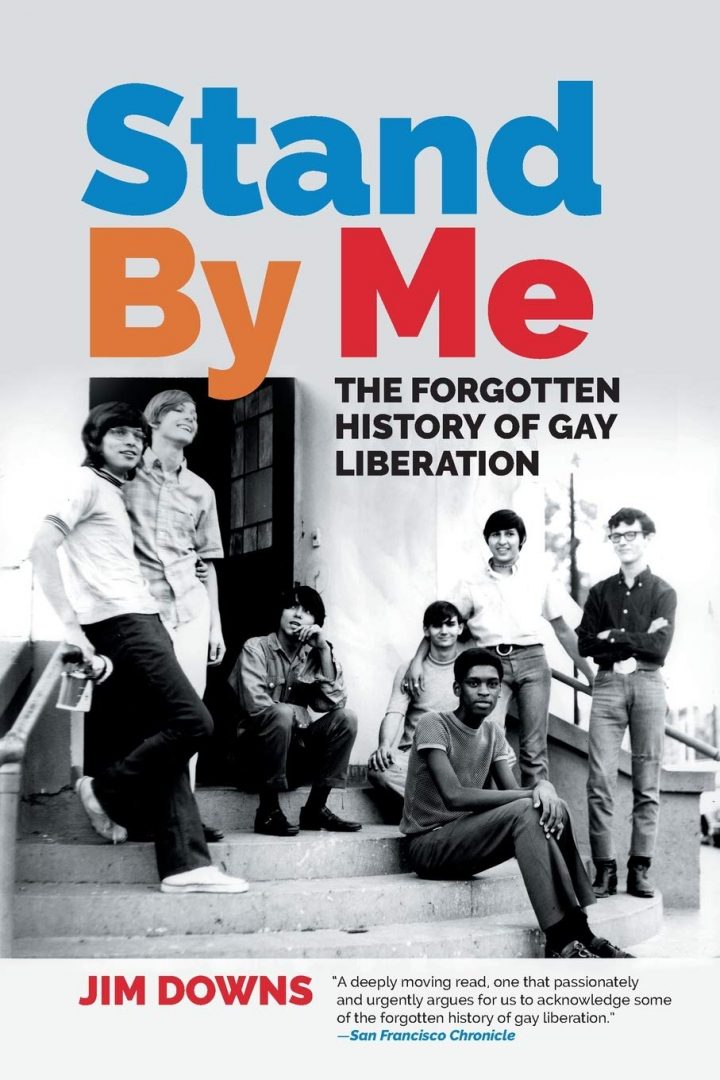

This anecdote about the personal and the political characterizes the exhaustive, but never exhausting, scholarship found in Jim Downs’s new book, Stand By Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation.

There are many ways to tell the history of gay liberation, as many fine recently published histories can attest. Lillian Faderman’s The Gay Revolution is perhaps the most outstanding recent contribution, but there are others. Over twenty years ago Sarah Schulman’s memoir My American History exemplified a new kind of queer historiography, embodying the second wave feminist phrase “the personal is the political.”

Stand By Me is not duplicative of other accounts. It is to our movement an equivalent to Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. Connecticut College professor and historian Jim Downs chooses several areas of focus to uncover a pre-AIDS narrative that does not reduce the late 60s through the early 80s to a simple story of seeking sexual freedom, as integral as that strand of the story is to laying a foundation for this movement. Downs begins first by surveying archival material donated by noted San Francisco activist Tommi Avicolli Mecca at the William Way Community Center in Philadelphia, and from there his inquiry leads him to a broader inquiry that reveals “how gay people built churches, founded newspapers, established bookstores, and re-thought the meaning of gay identity. I wanted to show how the 1970s was more than a night at the bathhouse.”

The first chapter is a detailed account of what Downs terms “the largest massacre of gay people in United States history.” Only recently has there been increased attention to the purposely set fire in August 1973 of the UpStairs Lounge in New Orleans in which thirty-two people perished. The bar was also home to a Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), and most of the victims had just attended the service which the gay church sponsored in the bar every Sunday night. In an era before cell phones or internet, Down details how gay people around the country quickly learned of the massacre, and of the indifference of public officials towards these deaths, and the disdain with which they held the victims. He credits the fledgling MCC movement and its leader, Rev. Troy Perry for drawing attention to this tragedy, and for providing leadership when government, church, and society alternately ignored or pilloried the people who lost their lives. It was not unusual for gay churches to meet in gay bars in those days, and Downs locates this event not in only gay history, but in the larger context of American violence toward minorities, citing the 1963 bombing in Birmingham at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

Each chapter leads to the next, a careful unlayering of another dimension of the complex cultural, literary, social, and political expressions of the lesbian and gay community in the years before AIDS. His next chapter on gay religious movements is the most extensive treatment to date of this topic. While contemporary scholars like Heather R. White in Reforming Sodom: Protestants and the Rise of Gay Rights focus on the debates on homosexuality in the mainline churches, Downs recovers the story of gay people self-determining their spiritual lives in groups like Dignity for Gay Catholics, Integrity for Gay Episcopalians, and the like. Noting the divide between activists in the period who decried the existence of these religious groups as self-hating, he nevertheless depicts how the members of these movements used the religion that had been used against them as a tool for liberation from the very same oppression. The churches that taught them to hate themselves also empowered them to repudiate that faith and form a new kind of spirituality. He quotes one early MCC minister candidly addressing the sex-affirming theology and practice they were innovating in gay churches, “There is no conflict for me in worshiping Jesus at service and then running out and sucking cock in the shrubs at the Fenway.” Another MCC’er refutes a critic in more elegant prose:

When you talk about Christianity, you are perhaps talking about the religion you knew as children, about the churches your parents took you or dragged you to, when you were younger. Perhaps, this accounts for your strange notion that Christian belief and gay liberation are contradictory. I certainly don’t feel a conflict within me.

In successive chapters, Downs recounts the central place that the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop held in this movement. He charts how Jonathan Ned Katz’s collection of primary source documents Gay American History formed a historical and ideological basis for the movement. Coming Out!, the play that was based on these documents was both entertainment and a pedagogical tool for helping gay people understand their place in history. It showed they had a history worth learning about and featuring. Katz placed the oppression of gay people in a lineage with the oppression of women, people of color, indigenous people, slaves and the poor. The pre-AIDS movement had a strong analysis of race, class and gender. The chapter on gay newspapers focuses principally, though not exclusively, on the Toronto-based The Body Politic, and highlights how the journalism also recovered lost histories, such as that of the Pink Triangle used to mark homosexuals in Nazi prison camps, and how the symbol was transformed not only as a reminder of the past but became a symbol of resistance and rebellion in the present. The international struggle for the freedom of the press in regard to these publications had a huge impact. It is hard to imagine the controversies addressed in these early publications being addressed in today’s more assimilated LGBT publications. Downs emphasizes continuously the inter-related nature of feminism and gay liberation, and also the role that socialist politics played in the movement at that time. His chapter on gays in prison is salient today as we continue to examine the inequities of our system of mass incarceration. His final chapter on body image and the construction of the “Macho Clone” and its destructive impact on diversity as a value also speaks to our conversations today about racism in the gay community, and the importance of Black lives and Black bodies.

According to Downs, the rise of AIDS results in a kind of amnesia. Downs is critical of the narrative that focuses disproportionately on sex and sexual expression as the through line, suggesting this is how our movement rationalizes the spread of AIDS, as a result of unbridled sexual promiscuity. An unnuanced reading of this text might cause one to see his tone as sex-negative, but a closer reading reveals he is simply placing this thread in context with the often overlooked proliferation of the gay and lesbian culture we invented almost ex-nihilo out of the maelstrom of the 1960s. In order to survive, gay and lesbian people created community in all of its forms. They found refuge:

At a service of the MCC. In the pages of the Body Politic. At the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop. At the theater staging Gay American History. Gay people in the 1970’s found one another and together created a lexicon, an idiom, newspapers, prayer groups, churches, beauty contests in bars, bookstores of their own- a culture and history that said their name. That culture, now largely forgotten, sustained them as they stood together as a community inspired by the promise of liberation.

I am grateful to Downs for telling these stories. This is the gay life I inhabited before AIDS. While I visited the backroom of the International Stud in the Village in the 1970s, I spent more time and truly discovered myself as an 18-year-old college student coming out in New York City at The Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, where Rita Mae Brown signed my now dog-eared first edition of Rubyfruit Jungle. I learned to free myself from pathological religion by attending services at MCC. I participated in consciousness-raising discussion groups at a precursor’s building to the current LGBT Community Services on 13th Street, in a scary warehouse at the convergence of Hudson, 9th Avenue, and 14th Street, the Triangle Community Center operated by MCC. I know my story isn’t unique. Down’s reclamation of the radical roots of the movement helped me understand why it was a collaboration between A Different Light Bookstore and MCC San Francisco that fed homeless people and worked against the express wishes of the Castro Street Merchants Association in establishing the first queer homeless youth shelter in the Castro District. It made me smile with appreciation that the activist whose early papers motivated Downs, Tommi Avicolli Mecca, is now a distinguished housing rights activist in San Francisco.

The world Downs describes is rapidly disappearing. Gay churches and synagogues have experienced precipitous numerical decline in the recent years. Community-based bookstores and newspapers are suffering a similar fate. Downs challenges our movement not to let the horror of AIDS or the rush to assimilate cloud the memory of our roots. Stand By Me calls us to dig more deeply into the past in order to guide our future.

Stand by Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation

By Jim Downs

Basic Books

Hardcover, 9780465032709, 273 pp.

March 2016