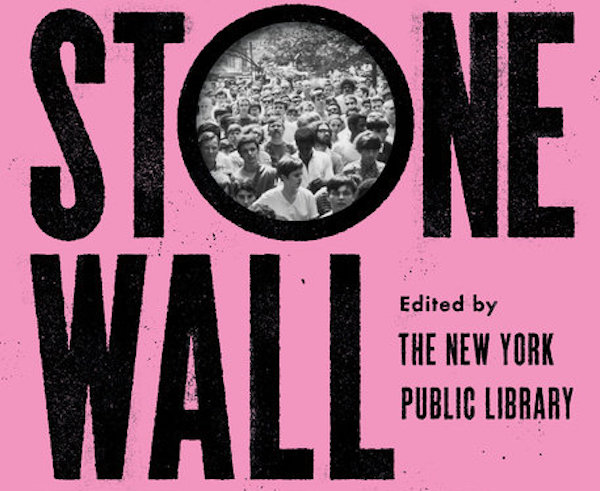

‘The Stonewall Reader’ Edited by Jason Baumann

Author: D. Gilson

April 28, 2019

“Many if not most historians would argue that major events such as gay liberation are not sudden but gradual, incremental,” Edmund White explains in his foreword to The Stonewall Reader, “[but] as someone who lived through Stonewall I would claim that the uprising was decisive.” White is, as the book goes on to show, both right and wrong. As Jason Baumann explains in his introduction, Stonewall “has become the stuff of queer legend and debate.” The Stonewall Reader beautifully dives into that legend and debate, and its strength lies in its queer messiness—first person narratives alongside journalist accounts alongside interviews full of delightful contradictions–a panacea, perhaps, for all the bad work that has been published on those sticky June days of 1969.

From the start, Baumann, who coordinates the New York Public Library’s LGBT initiative, dispels the myth that gay liberation began with the raid of the Stonewall Inn on June 27, 1969. “Stonewall was preceded by earlier queer revolts,” he deftly clarifies, “such as the Cooper Donuts Riot in Los Angeles in 1959, the Dewey’s restaurant sit-in in Philadelphia in 1965, the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot in San Francisco in 1966, and the protests against the raid of the Black Cat Tavern in Los Angeles in 1967, among many others.” His carefully curated volume also dispels the myth of white leadership surrounding the events at Stonewall, itself an important contribution, especially considering the horribly whitewashed 2015 film Stonewall, which centralized the story of a white cis twink fresh to the city as pivotal to the actions that took place in Greenwich Village. Baumann accomplishes this by not only diversifying the contributors to the volume–which include figures like Marsha P. Johnson, Audre Lorde, and Sylvia Rivera alongside Samuel Delaney and Mark Segal–but also by deploying a useful teleological organization to the essays, accounts, and interviews (“Before Stonewall,” “During Stonewall,” and “After Stonewell”).

“I remember how being young and Black and gay and lonely felt,” Audre Lorde writes in the reader’s opening essay, “A lot of it was fine, feeling I had the truth and the light and the key, but a lot of it was purely hell.” Lorde offers a context for why places like the Stonewall Inn (or Compton’s Cafeteria, the Black Cat Tavern, and a number of other key queer spaces) were so important pre-1969: everywhere else, or at least a lot of it, was “purely hell.” As Joan Nestle, cofounder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, puts it, “This was the Lower East Side, a place where gifts were laid at your feet, given by those who seemed to have nothing, yet carrying in their eyes and on their hands a broken radiance.” For these women and men, spaces like the Stonewall became respites from their everyday lives and points of convergence for those of varying class, race, gender, and sexual identities. This convergence laid the groundwork for the gay liberation movement that would define the next few decades. As Marty Robinson tells Mark Segal in these pages of the by-then-already-dated Mattachine Society, “You don’t want to be involved with these old people. They don’t understand gay rights as it’s happening today. Look at what’s happening in the black community. Look at the fight for women’s rights. Look at the fight against the Vietnam War.” Segal admits in response, “It deserves to be said right here and right now that the feminist movement was pivotal in helping to shape the new movement for gay rights… though some might have seen it as a sexual revolution, we saw it as defining ourselves.”

The culture at large, as it were, was afraid of us defining our queer selves. To them, we were dangerous. In her hilariously campy excerpt from “Gay is Good,” Martha Shelley manifests:

Look out, straights. Here comes the Gay Liberation Front, springing up like warts all over the bland face of Amerika, causing shudders of indigestion in the delicately balanced bowels of the movement. Here come the gays, marching with six-foot banners to Washington and embarrassing the liberals, taking over Mayor Alioto’s office, staining the good names of War Resisters League and Women’s Liberation by refusing to pass for straight anymore… I tell you, the function of a homosexual is to make you uneasy.

And perhaps we were (and hopefully are) dangerous. In Eric Marcus’s interview with the unlikely duo Randy Wicker and Marsha P. Johnson, Wicker asks Johnson of her involvement in the June ’69 uprising, “Were you one of those that got in the chorus lines and kicked their heels up at the police, like, like Ziegfeld Folly girls or Rockettes?” She answers assuredly, “Oh, no. No, we were too busy throwing over cars and screaming in the middle of the street.” The Stonewall Reader gives us a richer, messier, more dangerous picture of the Stonewall uprising, its foreground, and aftermath. The book wonderfully reflects how revolutionary moments rarely get portrayed accurately through single voices, and Baumann has produced here a history worth revisiting again and again.

The Stonewall Reader

Edited by Jason Baumann

Penguin

Paperback, 9780316524292, 336 pp.

April 2019