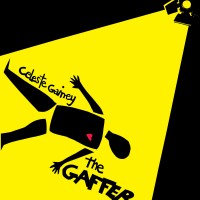

“Too bright/ is the heaven I’m after”: A Review of Celeste Gainey’s ‘The Gaffer’

Author: Julie Marie Wade

March 17, 2015

Celeste Gainey’s debut collection, The Gaffer, is a triumph of nouns—of people, places, things, and ideas presented to us in the most trenchant and timely ways.

You might consider beginning your exploration of this book on page 95 with the glossary, a place nouns have been known to congregate. In fact, I’m not so sure this glossary isn’t a poem in its own right with incisive descriptions like these: “a colored gel used in front of a luminaire to warm the source” (that’s #34 flesh pink) and “slang for a short-legged tripod; sometimes called a hi hat” (those are Baby legs) and “a low-wattage, Fresnel-lensed luminaire designed to light small areas; often used to fill the eyes” (that’s Inkie). Any graduate of this glossary will find herself initiated into the provocative lexicon of The Gaffer. She’ll be ready to turn back to the first page and begin again, fast- tracked toward illumination.

And from that very first page, the reader should prepare to be dazzled by an array of nouns on parade, the real things of this world teetering between disguise and revelation, camouflage and striptease. For Gainey, “show, don’t tell” isn’t just a technique; it’s a credo—a poetic principle elevated to a cinematic art. You’re not really reading Gainey’s book so much as you are watching it, the poems luminous and fluid as moving pictures on a screen.

One Halloween night in NYC, you’ll look on as “an Idaho potato/ hails a taxi.” One Christmas morning, you’ll watch as “Santa brings [our speaker] the Broadway soundtrack/ to Cole Porter’s ‘Anything Goes.’” Later, you’ll be wincing as “[Her] brother strings [her] life-size Davy Crockett doll/up on a eucalyptus branch, breaks its neck,” as her father “grows a brain tumor the size of an alien’s fist/and drinks himself to death.” Just like the movies, everything in this book happens in perpetual present tense. The images pass through you, and just as Eliot said, “All is always now.”

Our speaker is looking, too, and we are watching as she watches, following her eyes as they travel, then alight: “every morning the serene Pacific/ is the first thing I see as it lies a mile//or so down from my hilltop window.” We join her for self-assessments: “[the handkerchief] looks snappy/against the imported alpaca/ of my sport jacket, /the collar of my very white polo shirt/ spread open, a la Billy Haines,/ the tan of my smooth skin peeking through.” We peer over her shoulder as she pens a letter: “You’d never believe/ the sights—these clouds! Wow! Big as giant/ mushrooms!” We squint as she visualizes her desire, the hardest human truth to bring into focus: “all I really want is the ultra-white Dutch door, upper-half ajar,/ slice of Turrell blue bleeding through.”

The Gaffer is our guide. She is the first person we meet on the set of this story, the one who shepherds us through. We grow up with her “on the front of a postcard,/ the Riviera of the U.S. they call it, the town of the newly wed & nearly dead,// the cemetery by the sea.” We are standing by as she tells her mother, “When I grow up, I’m going to be a man”; as she tells the girls in junior high, “When I grow up, I’m going to play the field”; as she confides, “In high school I meet a boy/ I either love or want to be.” In fact, at some point we realize, we’ve been shadowing our girl since she was “a boy in a kilt and knee socks.” We’ve lingered as she passed through film school, applied to the Union Local 52, became a Best Boy (“there are no ‘best girls’ per se”), perhaps even the best Best Boy. We puffed with pride when she lit Lucille Ball.

We know her as best as The Gaffer, her title role and poem, “lamplighter/ chief lighting technician/ the DP’s go-to guy.” But there are other nouns she’ll appraise, other names she’ll entertain and perhaps even answer to. As with our own, The Gaffer’s identities are always multiple, always relative, a teeter-totter of more and less: “more gay/than queer/more queer than lesbian/ […] less woman/than man/[…] more butch/than dyke/ more dyke/ than trans.” We admire her honesty, knowing how the True Self is always plural, interstitial, on the move. She’s hard to pin down because she isn’t a still; she’s a reel. An Oscar-winning actress has this to say: “invariably there will be/ some on-set gaffer//who will have caught my eye.// To my very best friends/ I refer to her as my boyfriend./ I never touch her. Never talk/ to her even. She has no idea/ she’s my boyfriend.” But now we do, and we can picture the kind of boyfriend our Gaffer makes in a pair of “501s, brass button fly,/ washed-out watercolor blue,//worn corners on the right hip pocket/ where a wallet had been carried,// a slight cumulus cleft to the left/ of the crotch, where he had stashed his bulge.”

So, there’s a coming-of-age narrative here—a girl who wants to grow up to be a boy, who grows up instead to be a Best Boy, and after that, a Gaffer. But soon we see our protagonist illuminated by metaphor, in a poet’s masterful way: “An actor of the silent era,/ I learn to be manly & discreet,/ never disclosing our desire/ for each other’s sameness,/ how you give it to me—exactly/ the way I want.” By the end of the book, we watch her in “501s & Mighty Mouse T-shirt,/ 20 feet up, work gloves & pliers protruding.” Here again, she dazzles in metaphor, backlit by the myth of Icarus: “what’s that girl doing/ up there in the sky—flying so close to the sun?”

This Gaffer ransoms light from the sun to set her earthly world aglow, “to glisten & mesmerize.” All those people, places, things, and ideas, all those glittering nouns: we feel like we’ve met them, been there, seen that—on every page, in every poem. Gainey tests the limits of vicarious experience in this book, creating a poetics of fluorescence and neon. I keep thinking I might pop into one of her pictures, Mary Poppins style—each sidewalk-chalk sketch giving way to an enterable world. I’ve met Lucy after all, and the speaker’s “gay dad,” and the inmates at Alderson, Marysville, and Sybil Brand (“beautiful faces in lockup”). I’ve been to Vista del Mundo, where our speaker was born, and Green River Cemetery, where Frank O’Hara is buried. I’ve been to the 28th Street subway platform, the Papaya King at 86th & 3rd; to the Castro District the morning after the White Night Riots; the “National Cathedral in the dead of night.” I’ve even been to Washington Square Park “in the days of early polyester” wearing “the slinky boy shirt with the Kandinsky-like/ print” and “Byronesque collar.” I’ve been stared at, it’s true, and I’ve stared back.

Go ahead: flip to any page in this book, close your eyes, and point your finger. You’re almost certain to touch a tangible: “a blood-orange sunset,” a “midnight blue velvet blazer with wide lapels,” “a canary in a round silver cage.” The colors are so vivid. It’s as if the words themselves have been strung with lights, made all the more sensuous by Gainey’s masterful strobe. Don’t you want to slip on a pair of “brown & black houndstooth pants,” “green & putty argyle socks,” “tan leather driving gloves,” and “aviator Ray-Bans”? I do! Don’t you want to slide into a restaurant booth “among so many yellow placemats” and listen as “you tell me you love me/ for the first time”? I do! Don’t you want to notice everything, the way our speaker does, and watch it glide across the page in real time, unflinching Technicolor: “the maître d’ at his podium, little pillow of light/ over his face, oversize menus, flocked covers,/ tassels swinging, he ushers you into the low-/ceilinged labyrinth; lodge of plush booths tucked/ into nocturnal alcoves,// glow of tiny table lanterns bearding/ the famous faces.” I do! And so will you.

The Gaffer

By Celeste Gainey

Arktoi Books/Red Hen Press

Paperback, 9780989036122, 112 pp.

March 2015