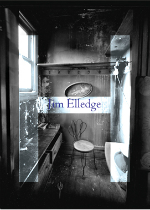

‘H’ by Jim Elledge

Author: Tony Leuzzi

January 10, 2013

When Walt Whitman declared, “Through me many long dumb voices . . . voices veil’d and I remove the veil,” our greatest American poet was making a commitment to speak of and for all the economically, ethnically, and socially marginalized people who might otherwise be trivialized or ignored. In the spirit of that commitment, Jim Elledge has written H, an intriguing collection of biographical prose poems about outsider artist Henry Darger. Informed by years of research (a formal biography will be released by Overlook Press in June 2013), Elledge paints a subjective yet persuasive picture of the artist metaphorically in the figure of “H” who, like Darger himself, begins as a sensitive, unprotected boy subjected time and again to turns of fate he cannot control, and ends as a haunted old man whose eccentricities and behavioral tics are misunderstood by those who cross paths with him in the streets of Chicago.

An in-depth knowledge of Darger’s life and works are not necessary to appreciate the many merits of Elledge’s book; however, a brief context will enable one to savor H more thoroughly. Darger is best known for his many drawings, collages, and watercolors of children whose forms he traced from various catalogues and newspaper advertisements. A number of these show children at play; others depict children undergoing forms of torture. Often, the boys and girls of Darger’s world run naked, with penises drawn in freehand on the crotches of both genders. Orphaned at an early age, Darger was exposed to various forms of sexual abuse, first in a boys’ home and then in an asylum for feeble-minded children; but, as is suggested in Darger’s own writing, some of the artist’s formative sexual episodes may have been welcome, possibly even self-initiated. Thus, H’s sexual experiences will be varied and—like the contrasting scenes of play and victimization of children in Darger’s drawings—capable of evoking terror, joy, or a complex roil of both. It is no accident, then, that some of the most powerful poems in H illustrate this complexity:

“Thermostat n. [<Gk. therme, heat + states, a standing]”

Tender and tense is H’s fifteen-year-old flesh, still rosy from the touches that filled last night. It was caressed then rubbed to warmth by a hand that wanted to rub a genii and all of the genii’s promises out of him, then by a mouth that was so hungry it almost devoured him. H nearly passed out. Desire left H in a stupor, tingling toe to crown, left H a candle burning brightly at both ends, left H fogged in, everything else he sees, touches, tastes, glittering. And nearby, wherever he might be—walking down the Asylum’s corridors to the head to brush his teeth, sitting in biology where Dr. Hook displays the body parts of children she’s autopsied, or gobbling up his dinner—he sees, out of the corner of his eyes, The Unseen pacing, tapping a vein.

By turns rhapsodic and menacing, the early erotic longings of “H” cannot be separated from his awareness of death and obsession with the palpably-impalpable force that pulls fate’s strings.

As with each of the poems in H, “Thermostat” is one entry in a lexicon comprised of 58 words. Taken as a whole, this lexicon erects H’s life through key concepts that Elledge proposes as crucial for understanding the artist’s internal landscape. In this regard, H is a book of language. “Grammar and syntax,” the poet says in “Algebra,” “that’s what H’s all about.” The nature of said language, however, is multifaceted. In some of the poems, it relates to H’s muddled murmurings; in others it speaks to the visual grammar of his art; but it also takes form as an expression of desire. In “Jeez,” H “adores skin-and-bone’s simple, direct lingo: how its words need yet give, take yet offer; how they begin then end without a trace (not place); how spoken they threaten to collide with one another but somehow never really do.”

Indeed, it is fascinating to observe how Elledge contextualizes, amplifies and thus, to some degree, knowingly distorts what few facts are available about Darger to construct a queer mosaic. The procedure involves intuition and a certain degree of improvisation, both of which enable Elledge to posit fascinating connections between Darger’s life and work. In many poems, for example, H embodies two genders: “a child’s voice . . . whether a girl’s or a boy’s” (“Toxic); “H raises his voice, no matter that he splits it into two: one male, the other female” (“Eclipse”); “his voice sometimes a man’s, sometimes a woman’s” (“Kiosk”). In such instances, the gender bifurcation alludes to any serious artist who must access feminine and masculine energies in the self to produce work of great power and sympathy. Thus, Elledge writes in “Delirium,” “Hero and villain, saint and sinner, girly-boy—that’s H’s life, hybrid of extremes.” Once again, echoes of Whitman abound, particularly in the embrace of contradiction and the coexistence of good and evil everywhere in the world.

Yet no consideration of Darger—imaginative or otherwise—could ignore mention of Elsie Paroubek, a young Czech-American girl who was kidnapped and murdered in 1911. Widely publicized in The Chicago Daily News and elsewhere, her captor-murder(s) was never found. For Darger, Elsie became the muse that inspired his fantasy novel, The Story of the Vivian Girls. As Elledge asserts in “Atrial,” Darger’s life was a “cross on a hill in a desert in which he daily hammers Elsie.” And if parallels to imagery in Darger’s art are not evident in that statement, consider the opening sentence of “Gauche”: “Elsie, your ghost is H’s sun and moon, your cries the stars, your last breaths the notes of a litany he sings to the Unseen.” Here Elledge understands that loss makes regeneration possible, that for H absence is the root by which imagination may flower—and endure.

H

By Jim Elledge

Lethe Press

Paperback, 9781590212509, 78 pp.

July 2012