Jake Schneider on Publishing Queer and International Voices in Berlin

Author: Lambda Admin

October 15, 2018

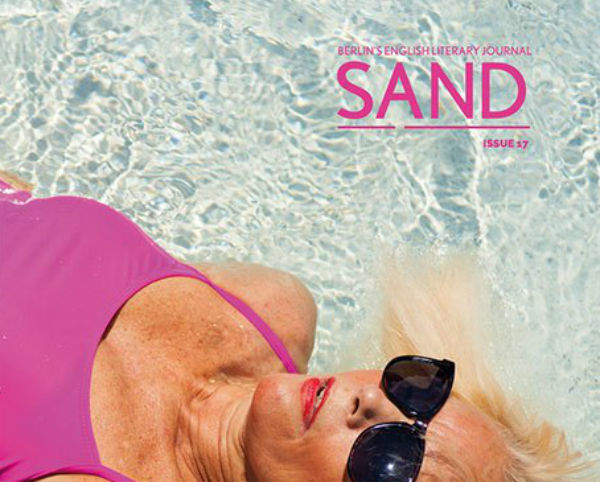

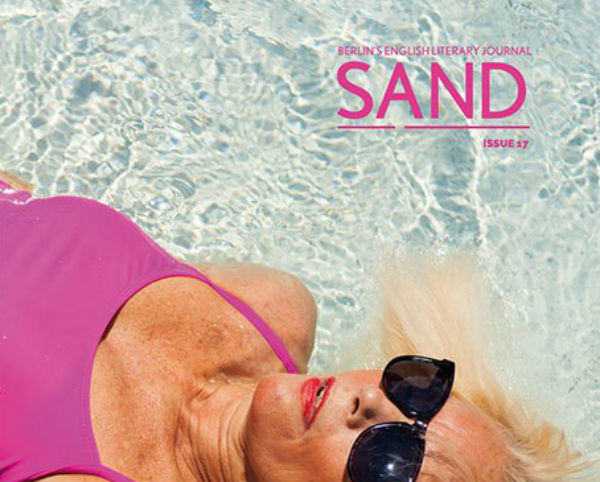

Jake Schneider is a translator and literary organizer. After studying creative writing at Sarah Lawrence College, he received a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship—the youngest recipient to date—to translate Fragmented Waters by Ron Winkler (Shearsman Books) and has lived in Berlin ever since. His literary translations have appeared in Words Without Borders, Circumference, Modern Poetry in Translation, and the Chicago Review, alongside more exotic cameos at a Carnegie Hall concert, a literary magic show, and the Venice Art Biennale. He is the editor in chief of SAND, a Berlin-based English literary journal.

Jake spoke with Brandi Spaethe of Lambda Literary about publishing an English-language journal in Berlin with a team of mostly non-German people and the queer and international stories you should be reading.

First, can you tell me about the focus of SAND? How did the journal come about?

In terms of format, SAND is your classic literary journal, a “little magazine” like so many others that are published out of passion from poets’ living rooms or university literature departments. We don’t have any thematic constraints: we publish what we consider to be the most exciting prose, poetry, and visual art that we can lay hands on. What sets us apart, I think, are the same things that brought us all here to Berlin. We read things from a different vantage point.

Becky Crook founded SAND in 2009 as a forum for the city’s Anglophone writing scene, which was just picking up steam. The vast majority of our team have always been non-Germans: from the US, UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, etc. Because it was always a community project, a team effort, the journal has managed to survive the many comings and goings.

Over time, SAND’s relationship with Berlin evolved: we live and work here, we’re active on the scene here, but we publish work from everywhere. In Berlin we’ve found like-minded people: we’ve become foreign just as we’ve made new homes. With our journal, we’re equally excited about other outsiders–fellow transplants, queer and trans people, working-class writers, rural writers, people from overlooked countries and regions–who make fantastic art and deserve more attention.

What is the meaning of the title?

I honestly don’t know. For years we’ve been saying it was a line from a Lee Hazlewood song, but our founder has admitted that wasn’t the original inspiration either. Let’s call it an acronym for some very witty phrase.

You run the journal out of Berlin, but you publish in English. Have there been any challenges with working abroad?

I resist the idea that Berlin is “abroad” because it’s also our home. Immigrants like us should be as much entitled to create and publish literature as people who write in their birthplaces and national languages. Berlin is a unique enclave of transnational literature. I know of online and print literary journals and small presses in Russian, Italian, Hebrew, French, Turkish, and Spanish too. In 2012, a directory of foreign-language periodicals in Germany listed more than 400 publications!

Within that diversity of languages, English plays a unique and tricky role. For one thing, it often brings these international communities together. (Learning German takes time; most people arrive knowing English.) Yet it’s anything but neutral. It comes loaded with plenty of British and American baggage, which has often displaced and devalued other cultures. So, my challenge as the editor of an English-language magazine in Berlin is not to be another emissary for Anglo-American culture, but a mouthpiece for marginalized writers who deserve the attention of our language’s global audience.

Yes, there are many practical and financial challenges of not being based in a core English-speaking country. Though we now are a registered nonprofit, we do struggle to find funding, sponsorships, advertisers, or donors. We have just enough money for printing and can’t afford to pay our contributors yet, let alone ourselves. We’re working on it.

But, I should say, it’s also very liberating to be one step removed from the industry. Many of us would be qualified for “real” publishing jobs elsewhere, but we chose to live here, to earn money with other work, and to make SAND for its own sake.

You mentioned before that you publish writing with queer and trans themes. Does every issue include voices from the LGBTQ literary community?

Yes. There has never been an official quota, but we publish writing by and about the LGBTQ+ community in every issue. A few recent highlights include shelly feller’s delightfully quirky gender-playful poems (“spangled dandy, i / suture couture de rigueur”), Maija Mäkinen’s story “Yellowstone” about a woman separated from her wife in the apocalypse, George L. Hickman’s flash fiction about a group of trans men reflecting on their deadnames, and Ben McNutt’s terrifically homoerotic photo series of wrestlers.

SAND has published writers from all over the world, including the Philippines. How do you go about getting submissions from that broad of a writer-base?

This, I think, is one of the advantages of inheriting an older publication rather than starting a new one. We’ve been promoting our calls for submissions and publishing far-flung contributors for almost a decade, and we’ve been very grateful that past contributors have recommended us to their talented friends.

For example, in 2013, we published a poem by Tammy Ho Lai-Ming (Issue 10) from Hong Kong, who is at the center of Anglophone writing in greater Southeast Asia as a founding editor of Cha: An Asian Literary Journal. On her recommendation, we soon received more exciting submissions from other poets in the region, including Nhã Thuyên (Issue 14), who invited us to last year’s A-Festival of poetry and translation in Hanoi and Saigon. There, we got to know the fantastic Tse Hao Guang (Issue 17) from Singapore, who read at our last launch party alongside two of Tammy’s colleagues from Hong Kong.

This same grapevine led us to publishing the queer Filipino poet B.B.P. Hosmillo (and presumably brought us the vivid contributions of Filipino writers Arkaye Kierulf and Scott Platt-Salcedo). I believe Hosmillo mentioned us to the organizers of the MoonLIT LGBT+ Festival in the southern Philippines, who contacted us about their pop-up book fair. And that’s how I came to write to you!

Very long story short: talented writers often know other talented writers. It’s a very small world. If we do our job well, people hear about us and submit. We’re also eager to keep in touch with past contributors and other literary projects in many different places.

Who are some LGBTQ writers you admire? Who have you been reading lately?

Among the long tradition of fabulous English-speaking gay immigrant writers, I recently enjoyed Garth Greenwell’s What Belongs to You (Picador, 2016), a devastating story of sex and economic desperation set in Bulgaria. And I couldn’t put down The Spring of Kasper Meier by Berlin’s own Ben Fergusson (full disclosure: he’s a friend), a noir novel of barter and anti-gay blackmail taking place in the rubble of postwar Berlin.

I also strongly recommend the travel writing of Annemarie Schwarzenbach, a lesbian road warrior who documented her journeys from her native Switzerland to Afghanistan, Persia, and the United States between the world wars. Her translators, Isabel Fargo Cole and Lucy Renner Jones, are both key figures in the Berlin literary scene.

Finally, I’d like to recommend this year’s “Beyond Queer” issue of Words Without Borders, which includes work from several SAND contributors, including Nhã Thuyên, and is beautifully written and translated from cover to digital cover.

Is there anything else you’d like to share with the Lambda Literary community?

As queer people, unlike religious or ethnic minorities, we generally start out alone and discover we’re part of a community later. Call it our “You’re a wizard, Harry” moment. And that community is very international.

Sadly internationalism, like queerness, is viewed with suspicion everywhere. The best cure for suspicion is empathy, and the best source of empathy is literature.

Now more than ever, when the side effects of toxic nationalism are causing even some of the worldliest people to forget about problems outside their own countries, we cannot lose sight of our global counterparts. We should especially empathize with the hardships of queer exiles who have experienced persecution for their gender identities and sexual orientations, sometimes in addition to the horrors of war.

We should read stories like those of Alex, a refugee from Iran who was turned away at the Australian border under that country’s shameful asylum policy. Instead of finding refuge, he has been held indefinitely at the Manus detention center in Papua New Guinea, where homosexuality is a crime. When officials there tried to suppress the very reason he had fled Iran, Alex stood up on a chair in front of all the guards and detainees to announce he was gay. Think back to your own coming-out stories. Can you imagine the courage it must have taken to stand up on that chair, to stand up to those officials, knowing that this time he wouldn’t be able to escape the homophobic backlash?

We know about Alex’s story because writers are everywhere, even at an internment camp in the Melanesian rainforest. Behrouz Boochani, an Iranian journalist and fellow detainee at Manus, has written an entire book there about the ordeals faced by Alex, himself, and the other rejected refugees, a book he smuggled out one text message at a time. I can’t wait for the translation.

Writing is not political per se–but reading is a powerful form of listening. It is the transcendent specifics of literature that allow us to imagine ourselves in that room, on that chair, across those distances.