Anton Nimblett on Rewriting and Remixing the Classics

Author: Edit Team

October 14, 2019

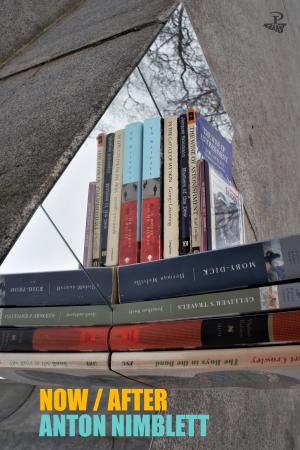

This August, Peepal Tree Press released Trinidadian born author, and current Brooklyn resident, Anton Nimblett’s new short story collection Now, After. In the collection, Nimblett remixes literary classics, by writers such as V.S. Naipaul and Herman Melville, by adding new emotional textures and an empathetic queer touch.

To celebrate the launch of the book, poet and critical writer Rosamond S. King engaged with Nimblett to discuss the collection.

Rosamond S. King (RSK): I have a very important first question that is inspired by a friend of mine. How do you feel about erasable pens?

Anton Nimblett (AN): [laughter] Who’s the friend?

RSK: It’s my friend Gabrielle. And this caused a great deal of, ahem, conflict in our circle of friends. These particular pens were the official pens of Project Runway, which is how she heard about them, so she decided to try them out. And I was so horrified, actually wrote a poem about the heresy, of eraseable pens. And then I needed to write in a book in which I did not want it to be permanent. So, I’m trying out the erasable pen.

AN: I have not tried erasable pens before, and I’m intrigued. And I’m also guilty of having watched more than a few episodes of Project Runway. How can the pens change my life? I feel like it’s a life changing thing.

RSK: Yeah, it is. And I still will cross things out instead of erasing. Sometimes I forget I have the eraser. And then there’s something to me about truth.

AN: ….And there’s a story in what we’ve crossed out and how we’ve changed it. In a lot of ways Now, After is about a looking back. The stories are inspired by looking back at what might have been there that wasn’t written, that was erased or just wasn’t ever written down. So, that’s a funky first question.

RSK: Segueing from what you just said, I’m curious as to how your writing has–or has not–changed between the first book, Sections of an Orange, and the new book, Now, After.

AN:  In writing this one, I was very conscious of trying to write the “better” book, a “stronger” book, just stronger in terms of the writing and the craft.

In writing this one, I was very conscious of trying to write the “better” book, a “stronger” book, just stronger in terms of the writing and the craft.

Recently, I read from the first collection, the title story, at St. Francis College. It has always been my favorite story to read. I read it and I didn’t have the same rush. I completely chalk that up to feeling that this [new] work is just closer to who I am now, closer to how I want to express things.

RSK: So thinking about the different inspirations, if I can call them that, the books that you draw from–you’re engaging texts that come from different canons, right? So the US American canon (Moby Dick), Caribbean literature (V.S. Naipaul), British literature (Gulliver’s Travels), as well as a calypso song. Did you choose favorite texts? Or did you choose them because they all had something in common? Did you choose things that you didn’t like?

AN: I have to say there is nothing that I don’t like on the list. So that’s the easiest answer. But they’re not favorites. There are so many authors who are favorite authors of mine, so many authors who I have learned from and have been inspired by who are not here Now, After. So they’re not favorites in that sense.

They were texts that I came to while the project was ongoing and in different stages. And there was a question, there was that thing that made me say, what’s up with this character? In the Lamming piece, “Something Promised,” there’s this Mr. Slime character. There’s a throwaway line [in the original Lamming story], somewhere in chapter 2 or chapter 3 where Lamming refers to Mr. Slime as having the fanciest ties on the island.

RSK: Mmmm..

AN: So I thought: Who does have fancy ties? Why dis man have a fancy tie, ent? And it’s just a throw away line. There’s nothing more said about his sexuality or his personal life in that sense, but much about that text questions Mr Slime and his motivation. I wanted to talk about why he has the “fanciest ties” and then how that ties back into the other questions of the role Mr Slime played in the [In the Castle of My Skin].

RSK: And so would you say that in each case, the, the writing is really driven by questions about a character?

AN: Absolutely driven by a character, but also a bigger question about queer lives and what those lives looked like before “our” time. I’m of an age when I see how different being a queer teenager now is from my own youth. It got me thinking about the past. What about a man in Barbados during the World War II era who was queer? What would that look like? What would that have looked like for him? Or a man in Haiti decades ago. How did he process his own feelings, if he was feeling something that we would call queer now? What did that look like?

Not all the stories in the collection are queer, but that was one of the definite driving forces in creating this collection…to imagine those lives that came before us. Those lives should matter to us because we didn’t just come from nowhere, having these queer, privileged experiences that we do now, as imperfect as they are.

RSK: It’s interesting that you mention that as a driving force behind the writing of the book. Because I would say, and you can disagree with me, that sexuality is not overt in your work. It does not follow standard gay literary tropes. Queerness is there, but it is not obvious. Sometimes you’re reading and you realize, oh wait, that is what he meant when he was talking about the fancy ties! Can you talk a little bit about about that and whether I’m reading that correctly.

AN: No, I think that’s a great reading.This was not a project set out to sort of reclaim or “queer” existing works of fiction. So I don’t want it to be “in your face” in that sense. I’m generally not in your face kind of person and my writing is not an in your face kind of writing.

I want people to reflect and say, “Aha, oh look at this!” I think that’s important to me as a reader; that’s important to me in terms of how I would like the work read. I’m fine with presenting someone with some kind of queer desire or queer thoughts in a nontraditional way. I think that’s really important, particularly when we think about how queer lives in the past existed.

RSK: The Caribbean is considered by a lot of people to be more homophobic than the United States and other places. One of the things that I think is interesting is all of your queer characters function within a community, and often within more than one community, including communities that are both queer and not queer. Even when there’s tension in those communities, there is some level of acceptance.

AN: It’s funny, I hadn’t thought about my writing that way. I think that’s how I think about life based on my experience and based on the experiences of people I know who currently live in the Caribbean, who have grown and developed and worked in the Caribbean. I think it has come through organically rather than by some sort of specific design.

RSK: To go back to thinking about the books that were inspirations, I’m curious: Do you see yourself as writing through the original texts, keeping the original stories and context as background? Do you see yourself as writing kind of alongside the original texts? Or do you see them simply as kind of a jumping off point into a completely different world? Does that make sense?

AN: That makes perfect sense. And my answer to that is yes [laughter].

RSK: [laughter] I asked for that!

Anton Nimblet: Because different stories do different things and I was very conscious of that while I was writing. You asked me this before and I didn’t answer it fully, but the choice to reference a calypso song and the choice to have texts from different canons as we call them, was very intentional. I wanted to have these writings exist in the same place. I want to say something about how these inspirations have equal weight in the world, certainly in my world. I also believe they should have equal weight in the larger world.

The “Farrell” story in the collection is a reply to the text, which is the lyrics of the calypso by Shadow.

The “Spouter Inn” story I see that as existing within the Moby Dick narrative, particularly that the counterpane scene in Moby Dick. The story seeks to investigate the Queequeg character. How does his past influence this moment, where we see him in this story in bed with another man at the Spouter Inn?

Certainly the story, “The Show” is jumping off from The Boys in the Band. And so there, I take more leeway with the established narratives in that there are none of the same characters. It’s not in the same time frame. But it is a investigation of what happens when you have five or six gay men in a space, that’s an intimate space, where people live and are having a structured party.