Justin Spring’s Obscene Biography

Author: Tom Eubanks

October 14, 2010

Too controversial for Vanity Fair? Secret Historian may be the Big Gay Book of 2010.

Justin Spring’s Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward is shaping up to be The Big Gay Book of 2010. It’s not often that a tome this scholarly contains so much sex and sadness. But that’s what makes this tale of a man, previously a footnote in the lives of his famous friends, so satisfying. (It’s also not very common for a Big Gay Book to come with its own even bigger, luscious, limited-edition visual addendum, but then Samuel Steward is no common subject.)

I had the privilege to meet with art historian and author Justin Spring between his appearances in San Francisco, New York City, and at the campus of Northwestern University—which, strangely, was the closest place to Steward’s old stomping grounds of Chicago that could or would host an event for the book. The way that Spring talks about Samuel Morris Steward, also known throughout his life as Phil Andros, Donald Bishop, Thomas Cave, John McAndrews, Philip “Phil” Sparrow, Ward Stames, D.O.C., Ted Kramer, and Biff Thomas, among others, is an awful lot like the way some speak of a deceased companion; yet, the two never met face to face.

Spring came across the gay pulp classics of Phil Andros in 1987, when he was just coming out. “I read all the books and loved them and thought they were kooky, sexy, but well-written social comedies with characters,” he recalled. “I’m not a book collector but there are certain books I would never part with. They were so strange and so unresolved in my mind.”

Steward died on New Year’s Eve in 1993, leaving behind in a West Coast attic, with 80 boxes of “secret history” for Spring to track down, comb through, and curate. The author eventually spent more than 10 intimate years with Steward’s diaries, drawings, archive of published material, and the “Stud File,” the alphabetized and annotated card catalog that accounted for every trick in Steward’s life, including the man’s rambunctious early conquests of Rudolph Valentino, Roy (soon to be Rock Hudson) Fitzgerald, an old and withered Lord Alfred Douglas, and an ongoing affair—of the most vanilla variety—with Thornton Wilder.

There were also letters to and reminiscences of a group of artists as varied as Cocteau, Genet, Cadmus, Lynes, Purdy, Isherwood, as well as Tom of Finland and Don “Ed” Hardy (yes, there really is an Ed Hardy; Christian Audigier merely licenses his tattoo designs for those godawful, omnipresent t-shirts).

It all seems like too much for one life . . . but then what would you expect from a man who was a professor at Loyola in Chicago by day and one of Kinsey’s favorite—and most faithful—subjects by night? A man who was an adoptive son to Toklas and Stein, wrote groundbreaking sex-positive pulps, and found himself the official tattoo artist of the Oakland Hell’s Angels?

Q: There’s something about your biography that’s so inspirational because although Sam died a failure in his own eyes, you’ve given him a brilliant final act. You’ve given his life purpose, posthumously.

Well, he had no idea any of this was going to happen when he died. And I think the sadness of his life was that he had a sense of everything not being sewn together properly.

What’s unbelievable is his run of bad luck from start to finish. I mean, he has a brilliant start with the one little novel that he published in Caxton, Idaho (Angels on the Bough), which is so crazy; but he gets a brilliant write-up in the The New York Times—he’s on his way! He knows Gertrude Stein; Thornton Wilder is his friend and lover.

All these great things are happening, and then, well, his drinking gets out of control. He dries up and then substitutes one kind of addictive behavior for another. But at the same time, he begins to see his work with and for sex awareness as being more central to his life than writing. Luckily, through his journals, he gets back into writing: about his sexual experiences at the tattoo shop and Chicago during the period after Kinsey really urges him to take it up.

So much of what Sam fell into after he got sober was really immersing himself in all aspects of sexuality and just becoming the most intensely sexual person. So, he chronicled all these sexual adventures very carefully in his journals and I found them so compelling; partly, I’m a bit of a voyeur, I suppose.

These are situations and types of people that I could never imagine getting together with. It’s a combination of his ability as a storyteller that compelled me but also the whole new kinds of experience that one can engage in sexually. I just wanted to have all of that in there.

His descriptions of the Embarcadero YMCA, for example: they’re so moving, they’re so sad, they’re so real. But all of that material goes into the Kinsey Archives and doesn’t come back out again.

Q: You write about having some trouble accessing certain things from the Kinsey Institute and the Beinecke Library at Yale.

The Kinsey library really didn’t want me to have access to all these materials because they’re afraid of getting sued. If I am able to trace back the origin of a photograph to the Kinsey that invades somebody’s privacy, the Kinsey is liable. They’re a much greater financial institution than I am.

Also, there are many, many organizations that are gunning for the Kinsey in a way that they aren’t gunning for an individual writer. The religious right is fiercely opposed to the idea of studying human sexuality and comparing it to any other mammal. The idea that humans are part of the animal kingdom is abhorrent to a large part of our population.

Q: Sometimes, it seems that our society would be just as upset—if not more—if Kinsey were to publish Sexual Response in the Human Male today.

No one was prepared for it in 1948. Everybody’s guard was down, nobody was trying to prevent such things from coming out. What happened was, when the female study came out five yeras later, that’s when it all really hit the fan. Not just because everybody realized how angry they were about the male volume but to talk about female sexuality was to really cross a line. You’re talking about people’s sisters and mothers and people get very up-in-arms about it.

There’ve been some gay people who feel like there’s too much sex in (Secret Historian). And they wish Sam would just get on with his life.

Q: Really?

For me, I’m like, what?! How can you say that?!

Q: Especially considering the time he was out carousing and recording his conquests. It wasn’t like he was doing this in the 70s when everyone was a whore. He was in the vanguard.

And in this whole cloak and dagger way where he was putting everything at stake. It’s as if he was addicted to risk as much as connecting to another human being.

In fact, that kind of repetitive tricking sexuality is not a necessarily about having a vital connection to anybody, it’s about being vitally connected to the sensation and to the novelty. So, I think maybe the gay readers who are not so happy with it are people for whom connection to another human being is a kind of central aspect of life experience.

There’s kind of sadness that all of this effort expended towards being sexual without having the other great benefit of being sexual which is to be emotionally connected.

Q: This book is not typical FSG fare. How did they come to publish it?

It was rejected at ten different publishing houses before FSG even took a look at it. My agent got letters from people saying you shouldn’t be peddling smut. “This really isn’t the thing that Justin should be writing; this is kind of shameful material.” I didn’t feel that way. After the bunch of rejections she said, “I don’t want to represent this for you anymore. I want you to do something more commercial.”

Go with God, you know? And I was kind of pissed off because I felt that it was saleable. So I talked to a friend, a magazine writer who is very smart about these things, and she said, “Get it printed as a magazine article and somebody will get excited about it.” I brought it up to Doug Stumpf at Vanity Fair and he said, “This is amazing but we can’t touch this, our magazine is too conservative.”

Q: Really? Vanity Fair?

He was editing a piece about Nancy Reagan as I sat there talking to him, so…don’t kid yourself. That magazine’s in bed with Hollywood and politics in a way that doesn’t have to do with down-and-out gay tattoo artists with long, sexual histories.

Q: This book reminded me in some ways of Serious Pleasures: The Life of Stephen Tennant from a few years ago, the failed writer and his famous friends—except the two certainly have different reasons for spending all their time in bed.

The book that inspired me the most in the writing of this was The Quest for Corvo: An Experiment in Biography by A.J.A. Symons. I’ve always loved the British biographical impulse to write extremely interesting biographies that take in as much life and times as individual accomplishments.

Sam’s accomplishments were not so phenomenal that he merited a biography, so in a way I had to prompt FSG, when I finally got my interview with Jonathan Galassi. I told them there was a high literary content but then I gave them a photo slide show of all the stuff I found in the archives. I was careful not to show them things that were too graphically sexual like you see in An Obscene Diary because there are, you know, pictures of Sam with a big cock in his mouth and that can be a little off-putting if you’re not in the mood to look at it. I didn’t want to shock him—I just wanted to say I’ve come across something that’s culturally and historically significant and would make a great biography.

He was aware of my Fairfield Porter book and trusted me as a writer. He saw that I had incredible material but he didn’t know if FSG could take on the project and he hemmed and hawed for a few days before he said yes to it. When he did, he was very happy with it. When I came back with the 600-page manuscript—because he didn’t even look at the original 1,600-page manuscript—he said something very sweet to me. He said I have two things to tell you about this manuscript: I found it incredibly depressing and I couldn’t put it down.

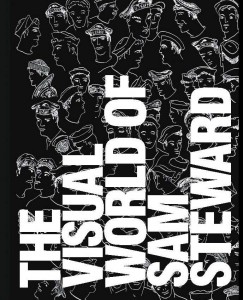

Q: Tell me about An Obscene Diary: The Visual World of Sam Steward (which contains scratchboard illustrations Steward did for his own translation of Querelle of Brest; erotic drawings; paintings; homoerotic placards from Phil Sparrow’s various tattoo establishments; photographs of his fetishistic collectibles, such as the Phi Beta Kappa paddle that makes an amusing appearance in Secret Historian; a selection of index cards from the Stud File; and black and white Polaroids of Steward with various non-camera-shy tricks engaging in what Steward called “spintriae,” “partouzies,” or (less coded) “daisy chains.”)

Just got my first copy! The printing was delayed in Italy. It’s a specialty book, printed in Italy, and they put it on a container ship and it’s only now just arrived. It was done by a man named David Deiss who runs Elysium Press up in Vermont. Finding a publisher who will deal with this material is hard. We worked awfully hard on it. There are only a thousand copies in print.

The rationale for putting the whole thing together is that I wanted all these materials for scholars and for people interested in writing on the period. Because this is not the kind of material you can put into a commercial book, and even if you were to put it into a library or manuscripts archive special collection, you’d have a hard time accessing it.

In large part, visual materials are not really accepted by archives. Places like the Beinecke really don’t know what to do with visual materials. In certain cases, they’ll accept them.

Since not everyone will be able to afford or find a copy of the book, I’ve been planning with the Museum of Sex (on 27th Street in Manhattan) to do an exhibition of Sam’s archive in February 2011. We want to have these works on display so that people can see them and get a sense of them.

Q: Has this process and this time with Sam’s papers and drawings and objects and those friends of his still alive teach you much?

I realized there are different iterations of desire; they vary geographically, temporally, and historically. A lot of my experience with Sam was watching the evolution of different kinds of desire and be able to watch it through one intelligent mind. Also, the level of intellectual engagement he brought to his sexual escapades and the level of emotional presence he had; you know there are people who go out and trick and trick and trick and it’s like they’re eating popcorn.

Sam had the idea that gay sex could be a life-affirming act and that had never really entered into the literary discourse previous. Even if you live in a culture that makes you feel bad about your sexuality, there is, through sexual contact, a sense that you’re in touch with something that’s much larger than other people’s judgments about who you are or what you’ve been getting into. For Sam to have come through the 20s, the 30s, the 40s, the 50s, and the 60s and to write that way about sexuality and even late in life, after he’d been through the ringer, is remarkable. It was his vocation, his art form, his métier!

Q: Do you miss him?

Yes—it’s like surviving a spouse, basically. We were in a ten-year relationship; I was closer to him at some moments than others. The last few years were kind of painful, and now he’s gone and all I can do is talk about him to other people. So, I’m coming out a kind of grieving process for that time I spent with him. I’m also glad to have my life back and also glad not to be dragged down into Sam’s miasma because he was a very dark and troubled man; it’s also nice to meet people who like him after the fact.

Or like the fact of our having gotten together. I don’t have children and this book is like a melding of me and another person.

Photo: © Stanley Stellar