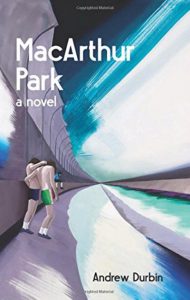

Andrew Durbin on His Novel ‘MacArthur Park’ and the Instability of Utopias

Author: Osman Can Yerebakan

October 4, 2017

In his first novel MacArthur Park (Nighboat Books), Durbin tells the story of an emerging writer, Nick Fowler, over the course of a few years, making stops at groundbreaking or mundane moments in his Brooklynite protagonist’s foray into self-realization. From the strike of Hurricane Sandy, throughout which Nick stays at his gallerist boss’s Greenwich Village apartment, to a random hookup at a London park, incidents in the character’s quest for a meaning as a writer and a young gay man in New York unfold into a powerful testimony on contemporary queer experience.

I met Andrew Durbin at his Bed-Stuy apartment to talk about his new book.

Either referring to the namesake Donna Summer song or the park in Los Angeles, MacArthur Park does not really have big impact in the book. Why did you choose this title? Does the title define the song or the park?

I’m interested in the way we invent a place as we encounter or don’t encounter it. The narrator goes back to the question of what one expects from a city or state or country and how one represents it versus the place itself throughout the novel, and he tries—through his own writing—to develop a working understanding of the American imaginary that has shaped and been shaped by California. In the novel, these questions crystallize when the narrator thinks of the song and the way it portrays the park as he drives past it.

In other words you are interested in the peak moment, a moment which is not necessarily the most important part for the plot.

I don’t think it’s an especially revelatory passage, but it does get to the heart of the book in terms of the questions it raises about the representation of a place. The Donna Summer song has a complicated history: it’s a long disco cover of a rather sentimental guitar ballad by Richard Harris. (The original is often listed as one of the worst songs ever written.) But it’s that translation—across genres and taste-levels—that my book wants to understand. The park has a very complex social history, too, from its role in gangland to immigrant activism of the late Bush era. It’s a place in Los Angeles that has eluded or at least complicated the narrative of gentrification.

Nick has traits of a typical protagonist of what Germans call Bildungsroman. His character encounters emotional and intellectual reformation throughout the pages, beginning with the first chapter about Hurricane Sandy through the café in Vienna. Between Nick and yourself, how has this progression evolved during the novel’s creation process?

Nick has traits of a typical protagonist of what Germans call Bildungsroman. His character encounters emotional and intellectual reformation throughout the pages, beginning with the first chapter about Hurricane Sandy through the café in Vienna. Between Nick and yourself, how has this progression evolved during the novel’s creation process?

Nick isn’t me, or at least I didn’t write him “as” me, but there are some obvious similarities between us, at least to those people who know me or have read my other work. The form of the Bildungsroman can be autobiographical, of course, but not always. In writing the novel, I was thinking much more of the downtown fiction of the late 70s and the New Narrative writers of San Francisco and Los Angeles, many of whom were interested in the ways autobiography can be used and subverted in ways that challenge traditional notions of the novel. My own book’s intimate tone approximates autobiography, but it’s not an actual memoir—it’s a quasi-imitation of one, or a performance of some of memoir’s tropes. Nick’s story is one that I suspect a lot of people can relate to, as people relate to many Bildungsroman protagonists…Stephen Dedalus, Young Werther, and so on. He’s someone grasping for meaning; he’s struggling to find, within a chaotic present, a larger sense of community, and himself, as a person and as an artist.

Whether a place or cerebral state, “queer utopia” is a strong thread in MacArthur Park. Broadly speaking, what was your understanding of this expression and how does such queer ideal determine Nick and the whole book?

Nick visits several communities that are attempting, in some way, to form a Utopia, but any intentional community, including the ones described in the book, require a complex, often curious set of rules and rhetoric to sustain that idea. In MacArthur Park, I wanted to explore those rules and rhetoric and their inevitable flaws, though I don’t think I’m very critical of the places I write about and/or invent. The cults and intentional communities with a strong utopian streak often find that the effort leads to a highly unstable, virtually impossible way of living and, as I write, a lot of the energy of those communities goes into denying that instability. That’s where my novel tries to go, into that instability.

That said, the protagonist’s obsession with hurricanes and cults challenge the understanding of a utopia and acknowledges a dystopian realm. How do you see the balance between the two?

Those are two significant poles in American life today. What fascinates me is the good chance that all of this will be destroyed because too few people are paying attention to what’s happening in the world. I think that’s a shame.

The certain parts of the book carry historical anecdotes, such the group exhibition Against Nature which Dennis Cooper co-organized with Richard Hawkins. Was it a challenge to incorporate fiction into recent reality, especially with topics that strongly relate the gay community such as AIDS pandemic?

No, it wasn’t. Gay life—gay history—are critical to my understanding of the world, of art, and so on. The world sill lives with HIV/AIDS, and there wasn’t a way for me to write a book about a gay man in the United States without somehow bringing that in.

MacArthur Park reads as criticism on contemporary art in certain chapters, commenting on works by artists such as Greer Lankton or Pierre Huyghe. As a novelist who is also an art critic, did you find yourself talking about these artists or you started writing the novels with the idea of touching upon these artists in mind?

The piece on Greer Lankton was published separately as an essay. The Tom of Finland section was also published as an essay, but in a very different form. In both cases, I knew that they would be a part of the novel as soon as I wrote them because I knew the novel, as I was working on it, would any many instances devolve into essays.

The depiction of posers for Wolfgang Tillmans at Spectrum is one of the strongest parts in the book, contributing to the notion of queer utopia, but also depicting a very contemporary panorama of gay revelation. Could you talk about that part and the influence of night life to your work in general? Spectrum is almost the important site in this book.

I moved to New York when the Spectrum first started, around 2011, I think. My apartment was a few blocks away. At the time, it was the great place to meet people, and that’s all that really mattered to me: new faces. Over the years, I developed a strong romantic attachment to it because I met so many of my friends for the first time there. It was my first experience of being in a place where my desires and my community seemed to be represented. Even another gay bar didn’t really do it for me. I felt that the stigmas against trans people, against women, even against people of color were still very strong, and that many people who went to, who go to gay bars were in denial of that. Whereas Spectrum provided this small room for people who were either queer, trans or people of color, and that was great, everyone wanted that, wanted people to be themselves and free; it was just different from what I had experienced of most of nightlife up to that point. Later I found other parties, other venues like it, but Spectrum was small and very concentrated, and that gave it a very peculiar life. It created a bubble—a bubble I later found I wanted to write about, especially as the Bloomberg years came to an end and neoliberalism seemed to triumph in New York. So, I wanted to write about this moment, the moment when the city began to erode public space. And yet, in all this, there was the Spectrum. But eventually it closed, too.

Nick reaches a transcendental moment while rimming a stranger in public in London. For a book that does not include graphic depictions of sex, that one part stands out as a very sexual and euphoric moment. What does that movement really mean for Nick and for you?

You always have to wonder what kind of sex your characters would have. Sex is difficult to write about because it’s so easy to fall into cliché. But the rimming scene just made sense.… I don’t know why. I haven’t read many scenes of rimming, so I thought I should give it a shot. I wish I could say there is any further meaning behind it [laughs], but it’s a part of life and anyone who has been cruising in public knows that this is just what happens. And, anyway, it was fun to write.