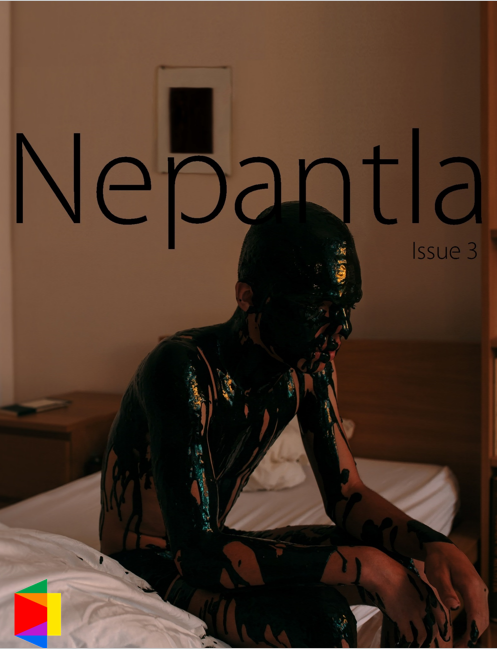

Read an Excerpt from ‘Nepantla Issue #3’: Brenda Shaughnessy & Christopher Soto in Conversation

Author: Christopher Soto

September 12, 2016

“Really it’s neither difficult nor devastating to hit a wrong note or to write a bad line of poetry. Just write another. Sing another song. Big whoop, I realized. But it took me decades to figure that out.”

This interview was conducted for Nepantla: A Journal Dedicated to Queer Poets of Color which will launch on September 16, 2016 (on the Lambda Literary website).

Brenda Shaughnessy is the author of four books of poetry. Her most recent collection So Much Synth was released in 2016 from Copper Canyon Press. Shaughnessy and I first met at NYU, where I studied under her in a poetry workshop course. In this interview we discuss music, writer’s block, safe spaces in queer communities, motherhood, and more. It is a pleasure to be speaking with her again for Nepantla.

Hello my mentor, thank you for taking the time to do this interview. I’d love to talk about your most recent collection So Much Synth which came out with Copper Canyon Press, earlier this year. Maybe we can start with talking about the process of creating the book. I heard that you were only able to start writing after taking voice lessons. Can you tell us about that?

After I finished my 3rd book, Our Andromeda, I felt drained; I had nothing left to say, my heart was wrung out and I was sick of myself. You know that feeling after you’ve poured everything into a poem or a book of poems, where you’re just embarrassed? All that stuff you wrote! Ugh! Suddenly everything that was private is now out there in a paradoxical way. It’s not private anymore, but that doesn’t mean anyone’s reading it. Whatever was precious and interior is now available to be ignored, as much as read. So there was a period of ambivalence and stasis.

One day I saw a Facebook post by the magnificent poet and artist Pamela Sneed, in which she said she was taking singing lessons and I was struck by that. Here was a woman who was undeniably one of the most powerful presences I’d ever seen. And she was going in to learn something new. It inspired me, so I started taking singing lessons with a wonderful instructor named Rebecca Pronsky (in Park Slope, Brooklyn! Poets, go to her!) and somehow the process of forcing myself to be embarrassed, just “letting it rip” allowed me to stop wallowing in bullshit. I had to face my own voice. It didn’t matter if I couldn’t sing. I could still learn. I could still submit myself to the discomfort of trying to get better at something I wasn’t good at, and didn’t know how to do. Sure it was embarrassing, but so what?

From the first day of singing lessons, for about 6 weeks, I could not stop writing messy, dorky poems and, as in singing class, I did not care how I sounded. Once I stopped worrying how I sounded, the poems flowed, surprising me day after day.

Embarrassment is so useful. We often just use it to shut ourselves up. But I found that I could use my embarrassment against itself: a new kind of fuck-you to an inner critic I hadn’t realized I’d been listening to my whole life. Really it’s neither difficult nor devastating to hit a wrong note or to write a bad line of poetry. Just write another. Sing another song. Big whoop, I realized. But it took me decades to figure that out.

How do you usually deal with writer’s block?

Writer’s block is just fear. When faced with fear, we fly or fight. Unfortunately, when it comes to writing, those two instincts merge into the same thing. We flee ourselves and we fight ourselves and in both scenarios no words get written. I wish I could face this fear the same way I would if I were about to get on a roller-coaster. Like, “I know I’m scared but it will probably be fun, if I don’t die or puke.”

Facing a blank page is facing mortality, it just is. I don’t know any way around that. It’s terrifying. But just as terrifying to turning your back to the page and running away. It will always be there right behind you!

There is a lot of music in these poems. Was that influenced by the voice lessons? I’m thinking about your poem “But I’m the Only One” after a Melissa Etheridge song. How does music function in this book for you? How does music relate to identity?

There are certain eras in one’s life where the music you listen to becomes inextricable from who you are, who you are becoming. Prepubescence and adolescence are such times, when you can channel the beginnings of sexual desire into the music you love. Maybe it’s not safe to explore sexuality at 12 with other humans, and maybe at 17 you want to explore but don’t have the chance to. Desire doesn’t go away just because you can’t express it. So we memorize the lyrics, we dance alone in our rooms, we make mixtapes, we get crushes on bands. For me this time was during the 80s, when synthpop was everywhere. Artists like Duran Duran, Madonna, Prince, and Erasure provided formative, ubiquitous, endlessly exciting coming-of-age soundtracks.

As for the Melissa Etheridge reference, that poem was set in the mid-90s, when that song was popular. At that time, too, I was coming into a new sense of myself as a penniless, heartbroken, poet-in-training lesbian in New York City. That song was an anthem for those of us who had nothing but passion.

I’ve heard you describe your second book Our Andromeda as a book to your son and So Much Synth as a book to your daughter. Can you explain? I’d love to hear more about femininity and adolescence and power in your poem “Is There Something I Should Know” too. (Also, I just discovered that is a Duran Duran song).

You just discovered that it’s a Duran Duran song?

Okay. I’ll just feel old for a minute here.

Minute’s over, now to your question. Our Andromeda is a book I wrote in part to process my transition into motherhood, a transition which, for me, was catastrophic. My son was not brought safely into this world and the trauma was and is profound. I wrote that book to save my life, and to be the strong mother I needed to be and have since become. My boy knows love, and security, and happiness, and he also has major disabilities which disallow most if not all of the rites of passage most of us associate with growing up. Then I had another baby, a daughter, who did come safely into this world, and she is growing up with all the typical ups and downs of a girl with no disabilities. It made me think, a lot, about the reality that even when there are no massive, obvious obstacles in one’s life, and growing up is still pretty perilous.

One night, talking with Craig, my spouse, fellow poet, and dad of our two kids, we somehow we got on the topic of girlhood, and what it was like growing up a girl. What it was like to be a free, happy little kid and to suddenly plunge, at age 11, into 700 days of nonstop hormonal chaos, an irreversibly changing body, sudden street harassment, sudden objectification, and this terrible sense of danger all the time. I described all these things and was blown away by how the ordinary, everyday experience of coming into womanhood was really so secret. I ‘d been so ashamed and afraid and humiliated even though everything was “normal” and nothing bad really happened to me. It was bad anyway! Ordinary adolescence meant coming into rape culture silently, unknowing, powerless.

I committed to writing about it, even though it wasn’t what I wanted to write about, because I had always assumed that we’d have found a way, by now, to stop or at least protest the rampant objectification, dehumanization, shaming, belittlement, and general degradation of young girls as a cultural norm. I figured by the time I had a little girl to raise she’d have less bullshit to have to deal with. I don’t know why I thought we’d have “progress.” Because it’s only gotten worse. Girls are in more kinds of danger now than ever before, things that didn’t even exist when I was a girl (internet predators, cyberbullying, etc.) on top of the old ones. It’s sickening. I wrote my truth to break silence in the face of that myriad danger. I want my kid to know (whether she reads it or not) and I want all of us who went through our own gauntlet to know that being a girl and becoming a woman isn’t an inherently disgusting, embarrassing, dangerous, unfair and humiliating thing. It shouldn’t be. We can call it out. I want my daughter to know that even if our culture surrounds her with cruel insults and threats to her humanity, sexuality, voice, opinion, mind, heart, and body, she doesn’t have to be silent. I want her to know that she is entitled to deny those insults and to defend herself against those threats, and to claim her power by believing in herself, in her truth.

Lately, I’ve been struggling to relate to some of my queer community because of trauma that I’ve faced inside the community. I am thinking about your poem “Why I Stayed 1997-2001.” How do you relate to your queerness now, after having two children?

Cruelty and violence inside the queer community is another place of terrible silence, isn’t it? “Why I Stayed” was something I wrote in solidarity with other folks who wrote about their experiences with intimate partner abuse. I felt safe in my lesbian community, but I wasn’t safe with my lesbian partner, and I couldn’t talk to anyone about it, even though everyone knew what was happening. I think there can be a lot of internalized homophobia—and overt biphobia—going on in situations like this: feeling one doesn’t deserve better because one has absorbed the cultural hatred of sexual minorities. This was back in the 90s, and many people weren’t out—lesbian life was a cherished subculture and I think some of us felt a terror of being seen as damaged or less-than, a terror of feeling unworthy of love.

I know that when I was living as a lesbian, I was pretty biphobic myself. None of us lesbians wanted to be left for a man, and for some of us, that’s what “bisexual women” seemed to threaten. But of course my biphobia was there because I was afraid of my own bisexuality, afraid because I was one of those “traitors”. Fun times! Once I came to terms with the fact that I loved who I love—that that’s all sexual freedom is about, being able to love who you love—I became much more comfortable with who I am, who I’ve always been. I’m still bisexual, even though I have two children begotten in the old-fashioned way. I’m biracial, and bisexual, and my two kids are both Geminis, so there’s a lot of double-ness in my world.

The book starts with a poem you published last year in the New Yorker, called “I Have a Time Machine.” This poem ends with the lines “I thought I’d find myself / an old woman by now, travelling so light in time. / But I haven’t gotten far at all. / Strange not to be able to pick up the pace as I’d like; / the past is so horribly fast.” Can you talk about how time functions in the book and in your life?

Well, that’s a big question because time is such a mystery, a lie, a constraint, a waste, a miracle, a waiting game, a Jenga game, an accumulation of vanishings, a constant failure, and also all we have!

Our entire lives have to be fit inside this time we have. And when I think about how few years a beautiful poet like Max Ritvo had, and how many years we’ve been deprived of the live presence of Lucille Clifton, and how the recent loss of CD Wright is heavy with the weight of years and years of her poetry the world needs but that time didn’t allow for [….]

Poets can’t beat time. We are stuck in our timeline. The words we write will maybe have more time than we do, but we must find the time to write them, line after line after line, if only because there will be a last line, and we don’t want to have already written it.

Thank you again for your friendship and your poetry!