John Chaich: On the Queer Connections to Books and Curating ‘Queering the BibliObject’

Author: Emily Colucci

June 19, 2016

Whether a record of same-sex desire, a space for envisioning queer worlds or a platform for the formation of communities across generations, literature has long been recognized as an essential art form for LGBTQ individuals. Even though the significance of its content goes unquestioned, the importance of the book as a tangible and, at times, fetishized object often remains unnoticed. However, a current exhibition Queering the BibliObject at New York’s Center for Book Arts until June 25 attempts to alter this oversight by refreshingly and radically investigating the physicality of books. Finding the artistic manipulation of books thoroughly queer, the exhibition is curated by John Chaich, an independent curator known for discovering queerness in previously underappreciated cultural practices like craft in his now-traveling Queer Threads: Crafting Identity and Community.

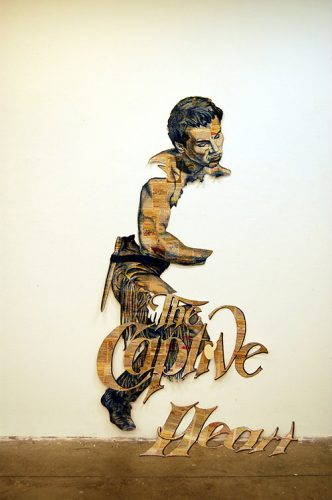

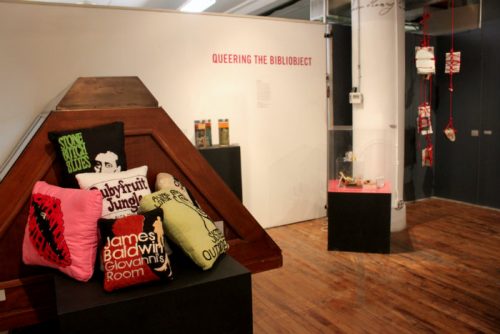

Bringing together a diverse group of multidisciplinary artists who identify as LGBTQ, Queering the BibliObject’s impact derives from the sheer variety of artistic expressions and affective relations to books, signifying the deeply held queer connection to literature. The art ranges from Aaron McIntosh’s Captive Heart Boyfriend, a wall-mounted work made from the cut pages of romance novels, to Tamale Sepp’s hanging and bound books and Eve Fowler’s gift-wrapped 62 Books, which effaces and restricts their titles and content. Beyond employing the book as a medium, the artists also honor certain iconic texts in the queer lexicon as seen in Stefanie Boyd-Berk’s sewn pillows of Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider and Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues.

Lambda spoke with John Chaich on the initial inspiration behind Queering the BibliObject, the reoccurring texts throughout the show and the narratives contained within his own personal library.

Queering the BibliObject takes an unexpected perspective on the significance of literature to the LGBTQ community by focusing on artists who use books beyond their typical narrative functions. What initially inspired you to delve into the intersection of LGBTQ artists and books?

I have to admit, my initial inspiration was rather solipsistic and nostalgic: I missed my books that were packed away in boxes when preparing for an ill-fated move to the west coast. In their absence, I realized how much their mere presence inspired me, and I particularly missed having books by queer authors surrounding me. That is, even if I hadn’t picked up a book like Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer’s Art and Queer Culture for months, it’s physical presence as an object in my personal space could trigger an idea or provide comfort. In this time, I also got to know Eve Fowler’s 62 Books piece, where she’s carefully wrapped in a custom screen print books of lesbian and feminist voices that were duplicates on sale at the ONE Archives in Los Angeles. Fowler’s work made me seek queer artists who are making work that explores how books work–physically, socially, conceptually–in our lives and spaces.

In the exhibition’s wall text, you point to Garrett Stewart’s analysis of the “bibliobject” in his Bookwork: Medium to Object to Concept to Art and Jennifer Doyle and David Getsy’s conversation in Artjournal as formative to the exhibition. Doyle and Getsy discuss a photograph of Halston reading in Andy Warhol’s library where the books are placed pages out on the bookshelves, which they see as a particularly queer gesture. Similarly, how do you see the treatment of books as objects in the exhibition as a specifically queer technique?

Thanks for making that connection, Emily. In his very thorough compendium, Stewart looks at artists who treat the book as a medium more than a form of media and in doing so, make us think about what books do in our spaces, identities, and relations. In this conversation, Getsy reminds that to queer something is to use an object against its intended use or its normative definition. Even though Stewart does not address queering or even queerness, I saw a parallel between between the acts of making bibliobjects and queering objects in that both deconstruct or reconstruct the book’s form and in doing so challenge how we think about the content. I guess you can say I had a queer reading of Stewart’s ideas.

In Queering the BibliObject, I think queering occurs in through four strategies: restricting access to the book (like Nayland Blake‘s grouping of found paperbacks that are contained and mounted plexiglass box); repurposing bound, printed matter as material or medium (like Jade Yumang‘s oozing pile of vintage gay porn that he hand-cuts through to create shapes that flow off the pedestal); reclaiming the book’s context and content in order to reimagine narrative (like Lucas Michael‘s drawings of the title pages of homophobic texts); and representing the self through, and/or relationship with, the book (like Leor Grady‘s shelf of James Baldwin paperbacks.) Of course, non-queer artists do this with books too, but I think that by creating art out of books instead of creating artists books, these queer artists are responding to the way that books, and spaces for books, shape our lives as queer people.

While the books’ narratives are often foreclosed in the exhibition, iconic authors appear as a type of shorthand signaling queerness. For example, James Baldwin appears several times in the show. What do you see as the role of these queer authors in Queering the BibliObject?

I’m really glad you’ve picked up on how references to certain titles or authors appear across several pieces. It happens a few times. Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider and Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues are both drawn by Allyson Mitchell and transformed into stuffed pillows Stefanie Boyd-Berks. Another pillow is James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, which is among the five Baldwin books that Leor Grady has arranged on a simple floating shelf. I bet if we looked hard enough, we’d find works by Baldwin and Lorde in Tony Whitfield‘s photographs of objects and books on his shelves too.

The frequency of these author’s works in the works in this exhibition testify to the far-reaching impact of certain authors in queer lives and the kinship and community that forms among readers. In the roundtable discussion with Anna Campbell, Nayland Blake, and Tony Whitfield at the Center for Book Arts, we talked about how we present ourselves through the authors on our shelves and how at certain times in our lives, particularly in the early 90s when queer theory and studies exploded, we could walk into queer homes and find certain titles, or you could gauge a person’s coming out process or even thought process through the titles on their shelves. Can the curated bookshelf signal as much as a red hankie in the left pocket or a labrys tattoo on a forearm do? How do we read each other based on who we’ve read, or as John Waters wonderfully put it: “If you go home with somebody, and they don’t have books, don’t fuck ’em!” I’m interested in how the artists author an idea by creating a piece using or inspired by a published queer authors work.

Two works that particularly stood out for me were Kris Grey’s video Precarity (Self Portrait with DSM) and Lucas Michael’s Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality, which both show books’ power to pathologize and repress queer bodies as much as liberate. Even though the artists’ appropriation subverts these texts, how do you see these works in conversation with others that employ iconic queer books?

There are several works that speak to the role of medical or psychological manuals in defining queer individuals’ choices, bodies, and desires. I think these pieces particularly embody the queering of the bibliobject that we talked about earlier–Stewart’s idea of how bibliobjects make us think about the book and Getsy’s notion of queering a book’s intended purpose.

In their video piece, Kris Grey balances a copy of the Diagnostic Standards Manual on their head; the DSM is used by mental health professionals to diagnose conditions. For a person seeking to transition genders, the DSM’s Gender Dysphoria is the required diagnosis one must achieve in order to have access to hormonal and surgical interventions on the body. In Precarity‘s endless loop, Kris stands stand before us, naked and exposing the extent of gender transition surgeries the artist has had. We are allowed to witness vulnerability as much as we see Kris’ stability and grace. (Kris never drops the book, a gesture that speaks to the gendered tradition of encouraging young women to balance books on their head to form perfect posture and the balance any transgender person needs to stand tall in this world.) In doing so, the piece exposes the complex relationship, even interdependency, between a trans person and the DSM.

In Bound and Determined, Tamale Sepp turns to antiquated etiquette manuals for young ladies behavior. She queers traditional gender binaries that these books prescribe by wrapping each using Japanese erotic Shibari knotting techniques, sometimes even puncturing through the books from cover to cover with rope and knots. The knotted books hang from the ceiling like bodies floating in combination of pain and pleasure, escapism and ecstasy.

Lucas Michael’s drawings are of of title pages drawn from books with bigoted texts or subtexts. He renders these drawings meticulously in graphite, signing them with his own hand and signature, and in doing so, takes back the power from the author and positions the books as objects to be critiqued.

I think these artists have found personal agency by reclaiming books and ideas that were designed to control them, and in doing so, these works encourage the viewers to reframe titles that may have oppressed or repressed their desires.

I started thinking about the affective connections across generations of LGBTQ individuals that occur through books, particularly as Heather Love–who also contributes an essay to your catalogue–explores in Feeling Backward. As Love describes the “touch across time,” what do you see as the emotional significance of books as object in the development of queer communities?

I am intrigued by how queer readers are “touching” ideas “across time” by touching a book by a queer author.

I’m so honored that Heather Love contributed an essay to the exhibition’s catalogue. In her essay “Bookish,” she describes how she was into books before she knew she was into women, or how she knew she was into women by being into certain books. Books provided a place of emotional escape and vision of a queer future for her as they do so many young readers.

Love describes books as “materials of identity,” and I love this phrasing. She’s talking about a kind of physical and emotional experience and attachment queer readers have with a book by a queer author. There’s a haptic quality. We are feeling a queer author’s in our queer hands as readers, and in doing so, feeling connected to a larger queer history and community.

Stephanie Boyd-Berks felt and cloth pillows are perfect examples of this: they materialize the notion of “curling up with a good book.” Or Paul Mpagi Sepuya‘s poetic photograph of a still life of books by or about Robert Mapplethorpe, Vita Sackville West, and Virginia Wolf also speaks to this. He arranges and captures the books as they are on top of each other like queer bodies caressing.

Stephanie Boyd-Berks felt and cloth pillows are perfect examples of this: they materialize the notion of “curling up with a good book.” Or Paul Mpagi Sepuya‘s poetic photograph of a still life of books by or about Robert Mapplethorpe, Vita Sackville West, and Virginia Wolf also speaks to this. He arranges and captures the books as they are on top of each other like queer bodies caressing.

Conversely, in pieces by Nayland Blake, Eve Fowler, and Anna Campbell, the artists control access to the book object, whether contained in plexi, wrapped in paper, or exposed but out of reach. How does this tension parallel queer desire to touch?

In the other catalogue essay, “Contrabrand Marginalia,” Scott Herring addresses queer spaces like libraries, where he’s found gay graffiti in margins of books and found books by queer authors in unexpected places that seem intentionally place to create a coding or invitation. When we encounter a used or shared book on queer ideas, are we touching previous queer readers through the oil and scent and curiosity now embedded in the fibers of the page? There’s a lot of feeling our feelings by feeling the book in our queer hands.

While at Queering the BibliObject, I couldn’t help but think of my own–admittedly messy–bookshelves, how I treat the objects and what narratives may be hidden there. Did curating the exhibition allow you to think differently about your own treatment of books as objects?

Funny you should ask. As fate would have it, I’ve recently moved again, and my books now piled and scattered among works of frames and canvases that have yet to find their place on my walls or shelves. Seeing this exhibition realized has made me question the role of privilege involved in queering the book as an object. On the one hand, the opportunity to even curate our shelves or acquire the bookcases or books themselves requires a luxury of budget, space, and even schedule, doesn’t it? On the other hand, buying and displaying used books is a form of preservation and taps into the affective quality that we talked about earlier. When I contemplate arranging my own books now, I keep thinking about Tony Whitfield’s work in this exhibition, where he documents how books interact with other objects on his shelves, from crystal phalluses to family photos. In the exhibition catalogue, I called my curator’s essay “Shelf/Life.” Tony’s works are a great reminder of how books give life to our shelves as mirrors of our queer selves.