Lexie Bean on the Power of Writing Letters to Your Body

Author: Karen Schechner

May 21, 2019

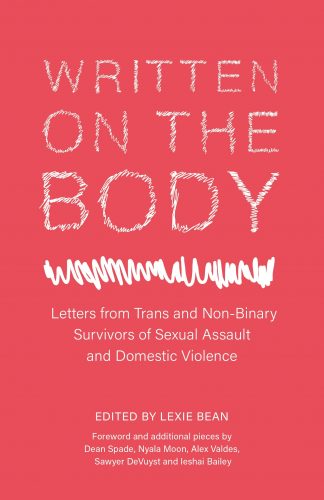

Writer, performer, and filmmaker Lexie Bean has edited a third collection of letters to body parts. In writing to their body, Bean, a trans survivor of sexual assault, said, “I can address and reclaim what is mine.” The letter-writing process gives contributors a powerful, poetic way to articulate trauma and reconnect with their physical selves. The collection, Written on the Body: Letters from Trans and Non-Binary Survivors of Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence, includes a foreword and additional pieces by Dean Spade, Nyala Moon, Alex Valdes, Sawyer DeVuyst, and leshai Bailey, and is a Lammy finalist in the category of LGBTQ Anthology. I recently spoke with Bean about the book, the power of writing letters to your own body, and their queer author heroes.

Writing letters to body parts is such an inventive form of expression and reclamation. What led you to this format?

I was in and out of hospitals throughout college. I wrote my first letters in the Neurology Ward of the Military Hospital in Budapest in 2012. I could no longer outrun my own body, and used letter writing as a way to reconnect with parts of myself that felt furthest away. This was before I used the words trans or survivor for myself.

Within days of returning to the States, I invited everyone I knew to write letters to their own body parts. I wanted our pieces to be witnesses, to be something that could move. This led to self-publishing two anthologies of letters to body parts, Attention: People With Body Parts and Portable Homes. With the latter, I came out publicly as a survivor for the first time. I became afraid of myself, of everyone. I ran again. I went back to Hungary and thought I would never write another letter. When I came out as trans years later, I knew I had to try again.

What is it about the addressing one’s body part(s) that empowers writers to find strength via vulnerability?

With PTSD and dysphoria, I have been in a long-distance relationship with myself for as long as I can remember. I can’t bring everything back at once, so I try to take it one piece at a time.

History is written into every letter, every imperfect intimate relationship. Therefore, none of the letters in Written in the Body were edited in content for a more “perfect ending.” None were grammatically edited without consent. None of the letters submitted were turned away. As survivors and trans people, we have worked hard enough to be believed. Vulnerability only comes when acknowledging there is no correct way to heal or begin dialogue with yourself.

The #MeToo movement, as essential as it is, doesn’t seem to address the sexual assault that the trans and gender nonconforming community faces. Was this lack of acknowledgement a catalyst for the collection?

The #MeToo movement, as essential as it is, doesn’t seem to address the sexual assault that the trans and gender nonconforming community faces. Was this lack of acknowledgement a catalyst for the collection?

The making of Written on the Body started well before the #MeToo movement. When I first started compiling letters, I spoke with multiple people and institutions within the publishing industry. Most discouraged me from continuing, as the project was “not profitable,” “too risky.” I decided to self-publish again. Thankfully, Jessica Kingsley Publishers reached out months later, and I turned in the final draft right around the time #MeToo filled my newsfeed.

Trans people are left out of mainstream conversations of sexual abuse and domestic violence. For example, the original #MeToo posts used the word “woman” to describe who it was for. As a trans boy, I immediately felt there was no place for me unless I claimed womanhood. It is no coincidence that trans men and trans masculine people are the most likely to commit suicide within the LGBTQIA community, and trans women and trans femmes are the most likely to be murdered or attacked on the street. Meanwhile, I have been told by representatives of a large public movement that there was “no time” for us. We have so much work to do. I’m thankful Written on the Body can be a part of the dialogue, and am open to conversation with anyone looking to expand “the movement.”

The entire book feels flooded with support for both the contributors and readers. What have been some of your favorite responses to the collection?

Anything in the realm of, “I didn’t realize I was survivor enough, trans enough until I read this book.” Perhaps I felt the same way until I started working on it too.

In Written on the Body, you say you’ll keep your voice on your nightstand. What does that mean to you?

Until a year ago, my bed was my least favorite place in the world to be. I would abuse over-the-counter medicine before allowing myself to get into it. I would often wake up with severe back pain or an injured hand from pressing into my side while asleep. My voice felt the furthest away while in bed because that’s where it mattered the least historically.

Written on the Body now fits on my nightstand, which is also a piano. The book is one of the closest things I have to an immediate support group. It’s where I can remember my own words, and how they can be held closely amongst others.

Who are your queer author heroes?

Andrea Gibson poems helped me through my hardest times in college; Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg changed the way l saw myself at eighteen. I just finished How to Write an Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee, a generous text that is already shifting my storytelling and listening. I am now reading my pal Jacob Tobia’s Sissy, and counting down for the release of Ocean Vuong’s debut novel.

My queer author heroes are also my roommates and friends, like Paul Aster Stone-Tsao, Laura Grothaus, Dana Levinson. Most of all, the contributors to Written On The Body, who kept me afloat through many forms of transitioning.

What are you working on now?

My first middle-grade novel, The Ship We Built, comes out with Dial at Penguin Random House in 2020. I have also been co-writing a television series with my pal, Paul Moon; we start pitching this year. Both projects are dear, personal, and located in identity and industry loss in the Midwest. I also speak at universities alongside Written on the Body contributors on trans inclusion in the #MeToo movement and more.