Philip Clark on Unearthing the Poetry of Donald Britton

Author: Christopher Bram

May 15, 2016

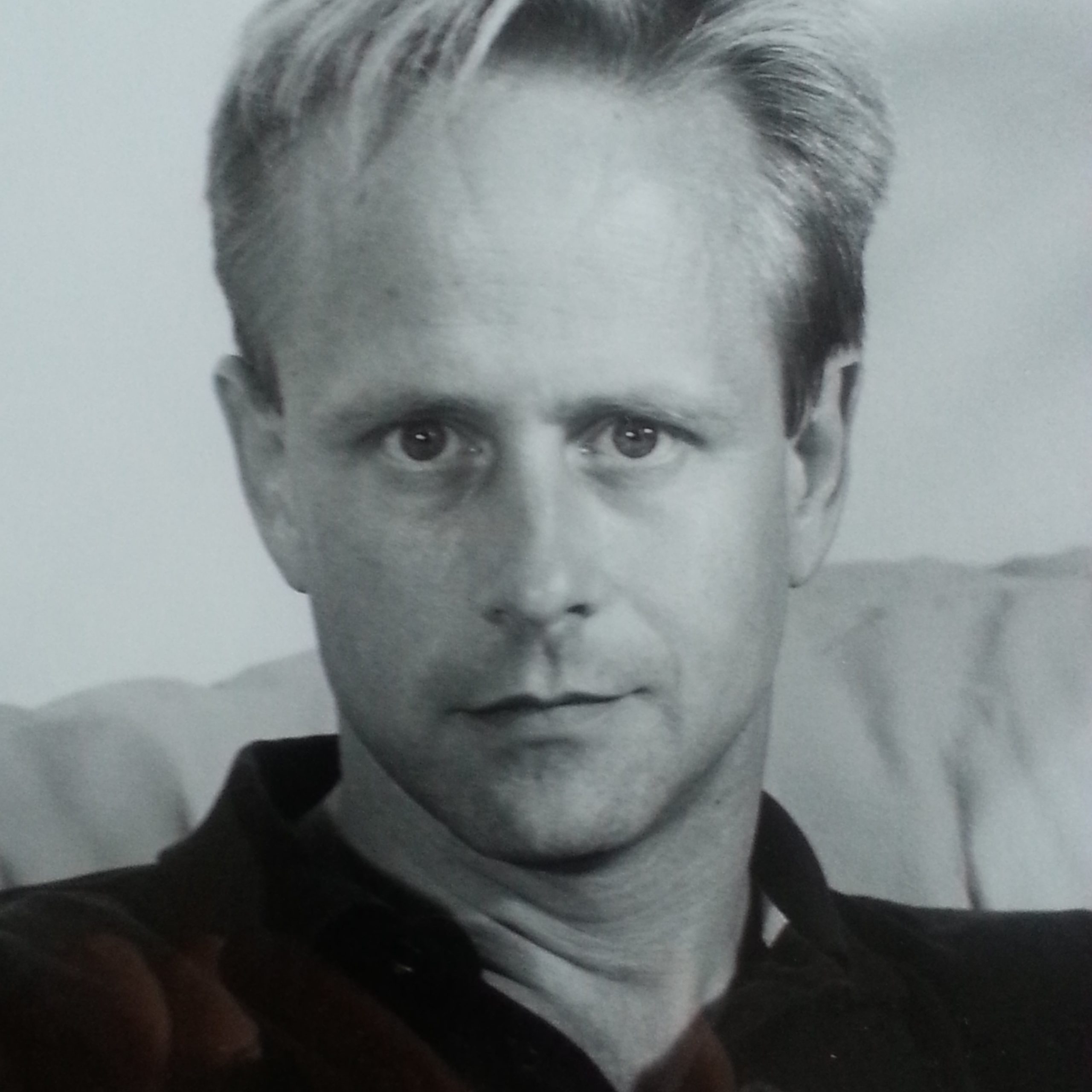

I first met Philip Clark in 1999, when I taught for a semester at the College of William and Mary in Virginia. I’d been in town only a few weeks when I received an e-mail from a man who wanted to know if I had any information about the late poet Walta Borawski, who I once mentioned in an essay. As chance would have it, I was good friends with Borawski’s surviving partner, Michael Bronski. I put Clark in touch with Bronski and he learned what he needed to know. Clark emailed me about other gay poets, none of them household names. I assumed Clark was a townie, an older gay man who knew and really loved poetry. Finally I suggested we get together. He came by my office and I met him: a tall, skinny, solemn 18-year-old freshman who looked like photos of young Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Clark had been reading gay poetry all through high school; I soon learned he was better read in the subject than many adult poets.

We have remained good friends ever since. Clark continues to read gay poetry, and he writes about it, too, regularly reviewing books on poetry and other subjects in the gay press. He has become a first-rate scholar and editor, discovering and reprinting forgotten work. He co-edited Persistent Voices: Poetry by Writers Lost to AIDS with David Groff, a beautiful, wide-ranging collection that includes both famous and unknown authors writing not only about illness but about love and family and everything else under the sun.

Clark is also interested in movies, photography (he’s written about photographer F. Holland Day) and a wide variety of 1980s music. Last year he was a contestant on Jeopardy. He works as a librarian in a public high school in northern Virginia.

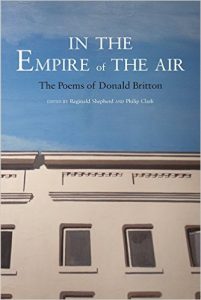

This month Nightboat Books is publishing In the Empire of the Air: The Poems of Donald Britton, which Clark took over after the death of the original editor, Reginald Shepherd.

Britton was a remarkable poet whose career ended just as it began. He grew up in Texas, studied literature at American University, and moved to New York where he hung out with poets and artists ranging from Joe Brainard to Brad Gooch to Dennis Cooper. He published his first book of poetry, Italy, in 1981. His verse is lean and lovely, using colloquial rhythms to suggest emotions rather than express them directly. Here’s a passage from the book’s title poem, “Italy,” evoking weeks spent in a foreign country:

We think a lot about emotion, chiefly

The emotion of love. There is much to cry about.

And after, sleep. One falls in love

So as not to fall asleep. I have just awakened

To the fact that I am not in love

And am about to fall asleep or write an opera

In which someone falls asleep and dies

Or write a letter to a friend or call somebody up

To meet me later for a drink. Maybe it’s too late.

A second book was scheduled to appear, but never did. He moved to Los Angeles where he died of AIDS at age forty-three, in 1994.

Clark and I recently spoke about Britton by email, building on earlier conversations that took place over coffee and burgers.

To begin at the beginning, who was Donald Britton?

Among people who never met Donald, I probably know as much as anyone—and he can still sometimes feel elusive. There are the bare biographical facts: grew up in Texas; attended the University of Texas as an undergraduate before heading to Washington D.C.; got his  Ph.D. in literary studies at American University while becoming immersed in a thriving local poetry scene; moved to New York City at the tail end of the 1970s; published one book, called Italy, through Little Caesar Press in 1981, and intended to publish a second, In the Empire of the Air, which never quite happened; and left for Los Angeles later in the 80s, dying from AIDS complications in 1994. Those facts only reveal so much, though, and are almost incidental to his poetry; as Reginald Shepherd says in the book’s introduction, there’s an “effacement of self in Britton’s poems.” We’re in an era with a hunger to know more about the artist, seeing the life as in some way a key to unlocking the work, but I think anyone who approaches Donald’s poems from that perspective won’t get very far. There are traces of his poetic influences—Hart Crane, John Ashbery—to be found in his style, and additional traces of the self-deprecation, restraint, and sneaky sense of humor that I’ve also seen in his letters. If anything, the poems are testament to an eye and a mind that was looking at the world on a different wavelength: there’s a remarkable particularity of language matched with fresh and jarring images. We’re more than 20 years after his death, and I’m unaware of anybody else to come along who writes quite like this.

Ph.D. in literary studies at American University while becoming immersed in a thriving local poetry scene; moved to New York City at the tail end of the 1970s; published one book, called Italy, through Little Caesar Press in 1981, and intended to publish a second, In the Empire of the Air, which never quite happened; and left for Los Angeles later in the 80s, dying from AIDS complications in 1994. Those facts only reveal so much, though, and are almost incidental to his poetry; as Reginald Shepherd says in the book’s introduction, there’s an “effacement of self in Britton’s poems.” We’re in an era with a hunger to know more about the artist, seeing the life as in some way a key to unlocking the work, but I think anyone who approaches Donald’s poems from that perspective won’t get very far. There are traces of his poetic influences—Hart Crane, John Ashbery—to be found in his style, and additional traces of the self-deprecation, restraint, and sneaky sense of humor that I’ve also seen in his letters. If anything, the poems are testament to an eye and a mind that was looking at the world on a different wavelength: there’s a remarkable particularity of language matched with fresh and jarring images. We’re more than 20 years after his death, and I’m unaware of anybody else to come along who writes quite like this.

What drew you to this project?

It was not so much a “what” as a “who”: the book’s original editor, Reginald Shepherd, first had the vision for what this project would be. When I was in high school, I had read poems by Donald that were published in the early 80s anthology The Son of the Male Muse. I wanted to include Donald in the anthology I was co-editing with David Groff, Persistent Voices: Poetry by Writers Lost to AIDS. Reginald apparently heard about Persistent Voices from Mark Doty, and he contacted me to be certain I was including Donald, whose poetry Reginald had loved for years and about whom he had written for Contemporary Gay American Poets and Playwrights. Reginald told me that he intended to edit Donald’s selected poems. I was able to put him in touch with David Cobb Craig, Donald’s surviving partner and executor, who introduced Reginald to all the unpublished work. I proofread the original manuscript and continued to stay in touch as Reginald worked to find a publisher. When he passed away before he succeeded, I knew I wouldn’t be able to let this book die with him. His final desire for this book to exist had to be fulfilled. The book honors Donald and his unique work, of course, but it also honors Reginald’s generosity in wanting that work to live again.

How much work remained for you to do after Reginald Shepherd passed away?

Reginald is this book’s real editor. Everything I did was nice, maybe, but optional, because the poems were already chosen and the introduction was already written. I didn’t remove anything from Reginald’s conception of the book, but because my basic orientation is as a historian and a researcher, I began to ask questions. Where had Donald’s poems been published? Was there any more work out there neither Reginald nor I had seen? Reginald knew about a couple of Donald’s publications, but because Donald kept no master index, there was almost nothing to go on. Using a list of magazine titles in Italy, Internet and archival research, and conversations with a few of Donald’s friends and editors, I was able to construct what I believe to be a fairly complete bibliography, although there are undoubtedly some early publications, in particular, that I don’t know about. Donald also had a habit of sending copies of poems to certain friends, and a number of otherwise unknown poems, or variant drafts, surfaced in that correspondence. I made a few judgment calls and added some poems, but I was very careful to note those changes inside In the Empire of the Air. Readers can judge whether the additions were warranted. Whether or not Reginald would agree with every choice I made, I know he’d be pleased that Donald Britton’s poetry will be made available to a new generation of readers.

What kind of input did Britton’s partner, David Cobb Craig, provide?

I think David is some sort of Platonic ideal of an executor. From the second I contacted him during my original research for Persistent Voices, he was unfailingly enthusiastic and supportive. Yes, I could reprint Donald’s work; yes, I could publish anything I wanted to; and he could provide more unpublished work, so did I already have enough to look at? Donald could not—no writer could—have a better and more accommodating executor. David had some opinions about poems or art for the book, but he always allowed me to make my own decisions, and he appreciates what I also consider to be the true goal: whatever else, get the work out there. Readers will find what they need, but not if the poems sit in a drawer or an archive or in a book that’s long out of print and hard to find, as Italy is.

What are your favorite Britton poems?

This may mark me as a philistine, because they aren’t the poems Donald ultimately chose to include in his two books, but I’m generally a bigger fan of the uncollected, earlier work. It actually took me quite a while to appreciate Donald’s style, in part because I came to his work with a distinct bias in favor of narrative poetry, and most of his poems resist all attempts at overlaying a narrative. (It’s like Twain said about Huck Finn: “Persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.”) Instead, they’re poems about states of mind, states of being, and ways of seeing the world, as in the opening to “White Space”:

A permanent occasion

Knotted into the clouds: pink, then blue,

Like a baby holding its breath, or colorlessAs the gush and pop of conversations

Under water. You feel handed from clasp to clasp,

A concert carried off by the applause.Other times, half of you is torn

At the perforated line and mailed away.

You want to say, “Today, the smithereensMust fend for themselves,”

And know the ever-skating decimal’s joy,

To count on thin iceGrowing thinner by degrees

But despite the receptiveness that has grown in me to Donald’s cockeyed lyricism, I still sometimes cling to the poems that evince a bit more of a story, even a subtle one: “Sonnet,” the ekphrasis of “Large Winter Scene” or “Zona Temperata,” and, among multiple variants, the particular version I chose of “Notes on the Articulation of Time,” which I think is amazing work. The opening two stanzas of a very early poem, “Hart Crane Saved from Drowning (Isle of Pines, 1926),” display Britton’s fascination with Crane, but also a set of telling details that relay a vivid setting:

He stood a long time while the USS Milwaukee

oxidized at the salt-wash pier. The succulent

hot stiletto beach pitched his nerves like waves

and waves bombed thunder cloud to palm.A dolphin materialized drilling

through serrated foam. Bacardi and fifteen-cent

Corona-Coronas slaked his thirst for sailors

now: he puked in volleys on ignited sand.

Readers will find their own favorites, though. Reginald’s preference was for the nine concluding poems, those intended for the original, unpublished In the Empire of the Air. He thought they were a leap forward, even from Italy.

Douglas Crase in his afterward provides a lovely portrait of the family of gay poets and writers that Britton belonged to: Tim Dlugos, David Kalstone, Joe Brainard, Brad Gooch, Howard Brookner, and Chris Cox. Would you like to talk about that world and the influence it had on Britton’s writing?

May I mention first how much I love Doug’s essay? It’s so carefully and beautifully phrased that each time I read it, I marvel all over again that we’re lucky enough to include it. As for your question, I’d say the world of writers and artists Doug emphasizes—the one he was also a part of—was another in a series of artistic groups from which Donald took sustenance. When he was at the University of Texas in the mid-1970s, he was a beloved member of the Shakespeare at Winedale program. He first met Tim Dlugos when he was living in DC, where he was also connected to the Folio group. This was an informal collection of poets that often gathered for readings at the Folio bookstore. They had ties to the New York School and with the emerging Language poets, and some of Donald’s earlier publications were in magazines members produced, such as Dog City, Là-Bas, and Sun and Moon. By the time he got to New York City, Donald had already established a pattern of combining friendship and art in very nourishing and productive ways. All writers could use the kind of community Donald consistently found. And the New York City of the early 80s was particularly full of these overlapping circles of artists, before AIDS arrived and destroyed so much. Of those friends of Donald’s you list above, only Brad is still alive. The losses are incalculable.

Your previous book was Persistent Voices: Poetry by Writers Lost to AIDS, which you co-edited with David Groff. What are the challenges of working with ghosts instead of living poets? Is it easier or more difficult?

I haven’t done a project of that magnitude with living poets, but I’m guessing it was easier, because there was almost universal goodwill toward Persistent Voices. Yes, there were one or two nightmare estates that shall go unnamed, but they were thrown into higher relief because of how celebratory the process was with everyone else. The executors were very pleased to see their loved ones’ work represented, and publishers all waived any of their normal reprint fees because it was a charitable project, with all monies going to the PEN fund for writers and editors with AIDS. Emotionally, though, the process could be draining, especially considering the tragic nature of the writers’ deaths. In some cases, usually when sending a list of potential poets for inclusion, I would inform someone about the death of an old friend or acquaintance or lover who they were unaware had passed. This would happen by e-mail, which I hated. Here I am, a stranger, delivering incredibly personal news in the form of some stark list of names. That I was treated so kindly by so many when dredging up unwelcome past events is a testament to the depths of the executors’ graciousness. I also felt a real sense of responsibility toward the writers. A few, like James Merrill, were famous and in-print, but most, like Donald Britton, were not, and Persistent Voices may be a reader’s first, and sometimes only, encounter with their writing. The choices I made needed to be fair and honest and representative of their best work. I had to help them shine, and perhaps inspire a reader to hunt down more poems.

Your next project is something very different, a biography of H. Lynn Womack, founder of Guild Press, a pioneering publisher of erotica in the 1950s and 1960s. Are you ready to talk about that yet?

Incessantly. Lynn Womack is known, when he’s known at all, for being an obese, albino philosophy Ph.D. and college professor who ditched academia in 1958 to publish gay physique magazines and who fought (and won) one particular First Amendment case, Manual Enterprises v. Day, at the Supreme Court. That’s what was known and said about him when he was alive, and that’s what’s known and said about him now. But his story has vastly more twists and turns. I’m going to argue that events in his life and publishing career serve as a mirror for most of the significant changes happening for gay men (and occasionally lesbians) from the 1920s through at least the early 1970s. It’s going to be as much a cultural history as a standard biography. There are all kinds of fascinating events and ideas and people that I’ll get to discuss, using as a hook the man who was known, by The Washington Post no less, as the “first king of pornography.” In the end, it will either be a highly significant piece of gay male social history or it will be an unpublishable mess that drives me around the bend. I’m about to find out which. After researching the book steadily for years, I’ll shortly be taking a leave of absence from work in order to write. It’s nerve-wracking, but necessary.

You are not only an independent scholar but a high school librarian. How do your two vocations feed each other? Do they ever get in the way?

I keep a fairly distinct separation between my vocation and my avocation, and I’ve always taken my research work more seriously than “my custom house,” my pay-the-rent job. On a purely practical level, the job keeps the lights on and finances my research trips, but it also steals vast amounts of time when I could be doing my real work, uncovering the gay past and telling its stories. Considering that books and writing were such a huge part of the development of my sexuality when I was a teenager, though, perhaps my being a librarian serves as some kind of homage to that period in my life. I’m getting to teach teenagers how to do research, after all, and research and reading was what helped save me when I was their age.

Do gay students know about your books or your reviews in the gay press?

I don’t sense that many high school students, gay or straight, find their teachers all that interesting. The couple of times school publications have interviewed me, I’ve always been honest and direct about my outside work and my motivations for it, but the kids don’t ask to know more. Still, I think that’s only natural. Navigating those years is pretty all-consuming without worrying about what the adults around you are doing in their off-hours.