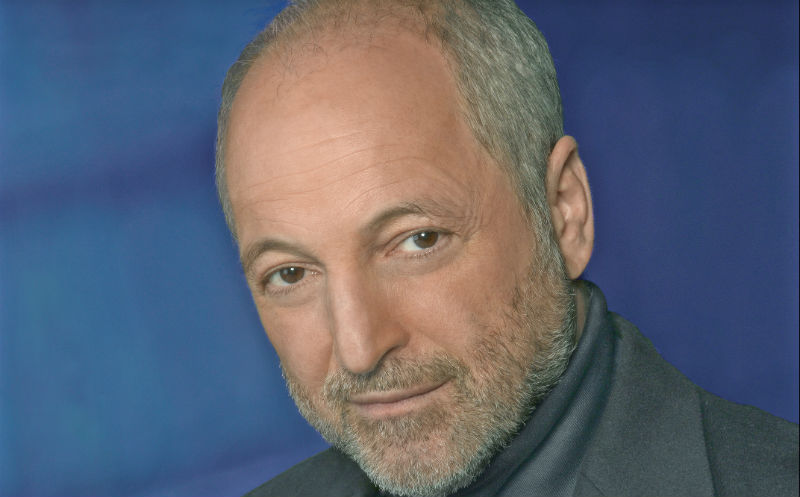

Author André Aciman on the Film Adaptation of ‘Call Me By Your Name’

Author: Lambda Admin

February 1, 2018

This winter, Call Me By Your Name, the film adaptation of André Aciman’s Lammy-winning novel, was released to universal acclaim. Directed by Luca Guadagnino, with a screenplay by James Ivory, the movie has recently received numerous Golden Globes and Academy Award nominations. The film, like the book, details the relationship between two young men who spend a summer in a small Italian village and whose growing attraction takes a series of unexpected, exhilarating, and mesmerizing turns. With actor Timothée Chalamet playing the young Elio and Armie Hammer playing older grad student Oliver, the movie is an evocative exploration of young romance.

The story’s narrative architect, André Aciman is also the author of Enigma Variations and False Papers, and the editor of The Proust Project. He teaches comparative literature at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Aciman took some time to talk with Lambda Literary about the adaptation of his novel and creating a “love” story that transcends labels.

Did you anticipate that the book and the film were going to be so popular?

Absolutely not. The film took quite a few years to put together, and when it finally happened, I figured, okay, it’s going to be a film and that’s going to be the end of that, but I had no idea that it would be nominated for any Golden Globes. I’m trying not to take it seriously, but how can one help that….

Especially when everybody’s trying to get ahold of you and talk to you about it.

Well, it was optioned after it was published. It was relatively soon after it was published, I would say within a year. Then the offer expired and it was renewed because the producer really believed in the book and stood by it. I had no idea he was going to stick to it and eventually produce what is, I consider, a fantastic movie.

Were you involved at all in the process of transferring it to the screen?

Not that much. I read some of the screenplays and by the time I got to the James Ivory screenplay, I knew it was a go. I had a few things to say, but I didn’t want to be intrusive. I was not going to be protective of my ideas and vision of the book.

I was on the set for a couple of days, and it was absolutely beautiful. They found a fantastic house in Crema. They kept saying that the house was a character. The look and the location informs the actual love story, and it works perfectly.

I saw the film first, and then I decided to listen to the book on tape because Armie Hammer narrated it. It was bizarre to switch my mind to his voice being Elio when he was Oliver in the film.

I thought the same thing. It took a short while for me to let myself drift into [Armie’s] voice. He did a fantastic job reading it. Not necessarily authoritative, although he has a deep voice, but it was pleasant to listen to.

I’m interested in how the endings are different in the film and in the book. I went with a friend to see the film and we both reacted differently to the end. He left saying that he was sad, and I was like, in what ways? He said, “I don’t know, for myself, I guess.” And I felt, well, a little, I don’t know if I would use the word sad, but I felt almost a loss of the high that fueled me through my youth. And I know that in other interviews you said that this sadness surprised you.

When you get to the end of the book, there’s an exhaustion that sets in, and I wanted a good finish that gave you closure without necessarily closing all the doors because I wanted it to be open-ended. I had no idea that people would start sobbing by the time they found out that the little girl had died, or that the gardener had died, those finalities. I don’t think the word “sad” is correct because it’s not an unhappy book. It moves you and people equate being moved to sadness. But I don’t think it’s that at all. If anything, you’re kind of enchanted by the whole process.

In the film, you get the same effect that you have at the end of the book. And yet the scenes are totally different. When you see the credits come up, you don’t expect them, nobody expects the credits. “It’s over and I don’t want it to end.” And what happens is that sensation, it’s not exaltation because it’s not a happy moment, but you feel enchanted. You are transported in a different zone and people get moved when they are transported either from absolute joy or absolute sorrow, but you’re taken elsewhere. And that’s what I wanted at the end. At the end of the film, [Elio] transports you.

I would agree with that. I think many viewers fall in love with them, and it’s almost like an ending of a relationship between them and the viewer. What’s interesting is that I was reading that Luca [Guadagnino] was considering doing a sequel. Have you been talking with him about that?

He spoke to me about it. I don’t know when he will do it because he is so over committed with other assignments. Who knows, maybe he wants to give it a few years and who knows what his enthusiasm is going to be like in a few years. But, it sounds like a nice idea. I did the book, that’s it. And if he wants me to do the screenplay, I will certainly want to try my hand at that.

In your novel, there’s not really much of an emphasis on it being a gay or queer relationship. That label doesn’t get used. And then I also noticed that you chose not to include any negative aggression from others pertaining to the main characters’ sexuality. Were these things you thought about when you were creating the story?

Yeah, absolutely. I didn’t want the boys in town making fun of the two guys. It’s not gone away by any means, but it’s kind of cliché at some point. I guess these were all easy cop-outs. But I wanted the love between the two men to exist, and I didn’t want them to be closed-minded to anything.

[In the novel] everything and everybody is open. Nobody is prejudiced. Nobody’s scared. Even the word love, which would have been so easy to use, I didn’t use in the book at all. It certainly looks like absolute and eternal love. If you have a world where everything is open, then the father’s speech may be surprising, but it’s not totally stunning. The viewer knew that the father accepted everything, so why should it be a problem? And I was so happy that this was the way it was. There were no sinister glances, nothing like that.

….And I think a lot of other people are interested in how sexuality operates beyond labels. And even the word “love” is a way of labeling a relationship.

It is a label. I also think that one of the reasons why people are so moved is because their father never gave them that speech and they would never have gotten that speech, so there’s a form of regret that they feel when they watch the scene with the father. But there’s also a sense that this could have been their adolescence. They say, “My God, it could have happened to me.” And so that retrospective glance that you have into your own life, especially if you’re in your 40s or even 30s, is very moving because you sense that your life took a turn that it didn’t necessarily have to take. I also hope that fathers watching this movie might learn something as well, that every father should give a speech like that.

Well, having grown up in Alexandria [Egypt] and Rome, you were mentioning how other parts of the world have resolved that relationship more than the US, and now you’re in New York. Would you say that this story also challenges how cultures vary in their expressions of intimacy and lust or how they might be similar since these characters are American characters living abroad?

People have made a big thing about the fact that the family is wealthy or they’re well-off. There’s a sense of… they’re not entitled by any means, but they’re living in a particular kind of world where it is probably easier to have a lax morality as opposed to a very sort of average one. I come from the Middle East, from Alexandria, where morality was extremely loose, but it was only loose among a very established and well-off circle. You go beyond that circle and you deal with people who are fundamentalist or religious, prejudice is extremely strong at that level. I don’t know how it is in southern Italy where the morality or the, the ethics, of the culture is more blinkered and more closed and close-minded. In the south when you’re from the Riviera or you go to Milan or Rome and Florence or up beyond that, you’re dealing with an evolved mentality where people are open to many things.

You placed the story in the year 1983. Was there a particular reason you chose that year?

I wanted to set it in [1983] because as I was writing, I realized, wait a minute, what about cell phones? No, I don’t want cell phones because when I was 17, which was not in 1983 by any means, there were no cell phones, and 1983 and 1963 are not that different. The culture of texting, of being constantly distracted did not exist. And I wanted [Elio] to have books, and the score sheets before him and you could focus on just that while Oliver would listen to his music with his ear phones or whatever he had. And that was good enough. Now we have a different way of relating to other people. You go to a café with someone, and they have their cell phone on the table, you have your cell phone on the table and constant texting and talking, texting and talking.

And I think the omission of modern technology creates a nice nostalgia. Not only for summertime, which is something that’s so instilled in many older viewers’ childhood memories, but also having Elio listen to the old radio and talking on the phone with a cord. There’s something really sweet about that.

Well, I don’t know if you remember when you were on the phone with your boyfriend or girlfriend, your parents could have been on the other line. You could hear a click and if your parents were nice it would be okay. They’d leave you to speak with your friend. I remember this when I was a kid. You had two phones in the family and the other phone could be picked up.

I spied on my family doing that. Mostly because my brother would never invite me to go hang out with his friends. I could hear him make plans, and I would get ready. And he’d say, “How do you always know when I’m leaving?” Just a wild guess. I kind of miss that, you know? Just having the cord and playing with it while talking on the phone.

Yes, getting it twirled up. That wasn’t very nice of [your brother]! Was the phone in the film on the wall or a cabinet? I can’t remember. I want to say it’s on the wall or it’s on a stand. But 1983 is distant enough for it to be a different world.

Were there any moments in the film that really impacted you, moments that stood out?

That impacted me? For me, the scene that was the most difficult to write, and I love that in the film it was taken almost word-for-word from the book, was a scene in which Elio tells Oliver, “I know nothing about the things that matter.” And Oliver says, “What things that matter?”

It was a very complicated scene because I wanted Elio to almost say something without saying it. But the understanding was that Oliver inferred what Elio was saying, that he was already on the same wavelength. But if Oliver had no understanding, didn’t capture the hint, that meant Elio wouldn’t say anything more. I wanted it to also be extremely oblique and that’s what happened.

As it was filmed, the two characters are watching each other, but there’s a statue between them, and there’s a bit of distance because the speech is distant. This one scene took me forever to write because I wanted to get advice from others about it. The people working on the film understood this and captured the whole ambiguity and intensity of the moment perfectly. And when Oliver says to him, “You know, we shouldn’t be talking about these things,” it means that he understood everything. He has gotten it, and he’s telling Elio not to go there and of course they change their mind as they start kissing.

It’s funny you mention that scene because I had it marked in my notes here. It was my favorite in both the book and the film. When Elio responds with, “You know what things, you know what things I’m talking about.” And while I was watching it, I was so thrilled because I’ve never seen that kind of admission between two characters when they’re having romantic feelings. I just thought it was brilliantly rendered.

He takes courage, says it the best way he could say it and plays it safe at the same time because speaking one’s feelings to someone when you have no idea how they will respond is extremely dangerous, and it makes us very vulnerable and nobody likes to confront that.

What was it like being somebody who doesn’t identify as gay to write a story about two men falling in love? Is this something that you get asked about a lot?

It is something I get asked about all the time and in many, many ways because the description of the act is so precise. If I’m going to describe the emotions accurately and as finely as I can, then I’m going to have to describe the act itself as accurately and as finely as I can. So people say, where did you get that experience? I never answer that question, because I don’t want to go there. However, everything that I write about is essentially furniture that I either borrow from people, or from my own life. I take what people have said to me. I take things from books, especially from books, and I cobble it together to create what I make. Whether it comes from my experience or not is irrelevant. It becomes true even if it never happened and people react to it as if it was absolutely true for them. And that is where it matters the most.

As Proust would say, I give people different lenses and you try this lens or try that lens, and you see better now and when they read me, I want them to read me with the lens that works for them. Nobody says this book is not true. It’s real because I think it’s very well-constructed. I can say that without any sort of vanity or anything like that. It is. It’s a tight story.

I have lots of people in my life. I got married very late in life. I was 37 and had a lot of experience and a lot of people write to me now from my past, which is not exactly something you always want, they write to me and say, “Was so and so me?” I tell them yes, even when it’s not them, because in part some shade of their existence has been transported into my book. Everybody is in the book. Everything I’ve done in my life is in the book.

I visit Rome often, some people come up to me in Rome and they say “take me to exactly the place where the two of you kissed,” and I say, “No, I’m not going to take you there because I don’t even know if it exists.” I do mention real streets, I mention cafés, I mention places that you can go to but some places I project from my past, and they don’t necessarily exist. You can imagine the disappointment of people when I tell them, no, I can’t do that because I don’t even know where it is.

There’s this fascination with wanting to have the experience of the narrative even though it is fiction, but people still want to believe that these are true and real places they can have some kind of experience with, too.

Yeah. And I don’t blame them. It’s like, you want to go to visit the house where Keats lived and so you go visit the house and you’re filled with disappointment because there’s not a thing about Keats there. In other words, yes, his bed is still there, but the poetry of Keats is not there. The real Keats is on paper.

Lastly, I’d just like to say that this is a very moving and incredible story that I’ll be thinking about for a long time.

That’s the best thing that can happen when you see a great movie–you wake up the next morning and it’s still there. If you saw it on a Saturday night, it’s there on Sunday morning and then it’s still there on Sunday evening and you say, “My God, I want to cuddle with it. Have it stay with you.” That this particular film, for some reason, stays with you. It doesn’t go away, and I love that about it. It stayed with me and I’m the author; I’m not supposed to be affected in this way.

You go to bed and you wake up in the morning, and it’s still there. Elio’s face is still staring at you.

This interview has been edited and condensed.