Yawp: Rocky Mountain High (AWP Recap)

Author: David Groff

April 18, 2010

Denver may not be exactly in the Rocky Mountains—its most mountainous feature is the white-capped roof of airport, situated on the flat plains east of the city, a lemon meringue pie for the gods. But Denver is definitely a mile high, which meant that the breathlessness experienced by the poets and prose writers attending last week’s Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference weren’t just panting from the nonstop talk. The air may have been thin, but the conversations were thick with smarts, sparks, and arts. We queer writers established our own virtual village amid the vast metropolis of poets and prosemakers thronging the Hyatt Regency and the Colorado Convention Center. And we generated a lot of energy at the various official panels and readings whose content and/or speakers were of direct LGBT interest.

RJ GIbson and Matthew Hittinger

(See my previous Yawp column for a listing of some of those happenings.) The words uttered at those events may have vanished into ether, but I think they might help incite writers into kinds of work that their readers will care about. And even when two or ten thousand writers congregate, it’s still all about our readers, right? Without those precious (and often precious few) readers who paw our pages, each of us might as might as well scribble in a diary and then swallow the key.

As always, around the great, lumbering grizzly bear that is official AWP gather myriad other woodland creatures—all of us who come together informally to chat, flirt, read our work, drink, haunt the book fair to score discount books and free Tootsie Rolls, make new AWpals, reunite with last year’s AWpals, drink, suss out jobs and gigs, compare notes, argue aesthetics, drink, and otherwise connect. Queer writers were front and center at the coffeehouses, bars, readings, parties, and receptions where much of the literary, political, and psychic business of the conference transpires. With so many creative writers gathered in one place, and with our measures of success and recognition so meager compared to those offered by the nonliterary world, at its worst AWP can make us feel like ants all swarming a single Rocky Mountain oyster. The conference is designed to make us aggressively insecure. But in spite of the inevitable identity mongering, the recitations of accomplishments and ambitions that can leave both reciter and listener breathless, I find that a near-childlike joy infuses AWP: once a year, an entire convention center is filled with those who care urgently about literature. Who wouldn’t get high from that?

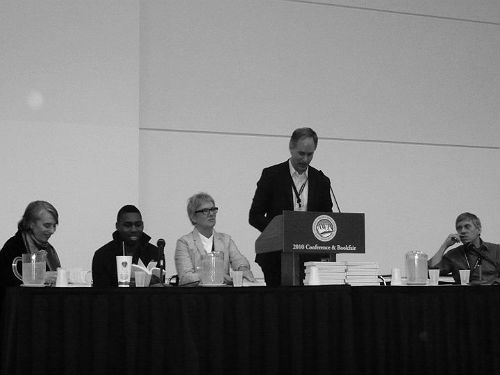

Joan Larkin, Saeed Jones, Elaine Sexton, David Groff, and David Trinidad

When I got back to sea level, I asked a lot of LGBT poets to tell me what one thing they would remember about the Denver AWP. Here are answers from the ones who responded:

Alex Dimitrov: It will be hard to forget the Bloom party Charles Flowers threw at the Wrangler—so many great queer poets like James Allen Hall and Randy Mann, who I rarely get to see in NYC. The energy was great, and of course there was those Britney Spears music video lights circa 1999. I remember reading the first issue of Bloom as a freshman in college, five or six years ago. I’m grateful to Charles for bringing it back.

Steve Fellner: At past AWPs, it took me a little bit of time to find a book by a queer male poet. And I have no reservations in saying that I put my money primarily towards gay male authors and their respective presses. I would wait and listen and search to find one, maybe two, perhaps a few more. What I liked about this AWP was the pure excessiveness of queer poetry. It was wonderfully nauseating to come across so much of it. From time to time, I was even annoyed, maybe slightly peeved–there was too much of us. It felt gratuitous. It felt like we were taking over with the sheer number of volumes, making heterosexuals’ mostly benign poems invisible. It felt like we were ruthless and necessary.

Charles Flowers: Walking into the Queering Desire panel and feeling proud the room was full, overflowing in fact. It felt like a historic moment somehow, even though it wasn’t the only LGBT event at the conference.

RJ Gibson: The thing that sticks with me is getting to connect and reconnect with friends or finally getting to meet people I’ve known only through email and as online presences. That and Robin Becker liked my shirt.

Christian Gullette: I would offer three particularly memorable experiences: 1) the Bloom party, 2) hearing the poems in Persistent Voices, and 3) making new friends. I thought the panels I attended were great, and so many queer-themed ones to choose from this year. They were inspiring. I’ll also remember being stuffed into a car with like eight people, having to lie across laps, one window missing, and getting lost on the way back from Tracks nightclub, all of which was really fun.

Christopher Hennessey: I remember talking to Jan Beatty and RJ Gibson at the Bloom party at the Wrangler. Or rather I remember telling Jan that the poetry she and other read for their panel was HOT! (Writing Sex: Implicit Censorship in Contemporary Poetry) And how embarrassed I was halfway through when I realized I had been holding my satchel over my lap the whole time as if I were trying to hide…you know, some sign the poetry was arousing me. I mentioned that David Trinidad was sitting beside me and said that that’s surely what he must have been thinking but that I hoped not. Jan laughed and said he probably would have got a kick out of it, that poetry could (does!) have the power to put fire in the blood!

Matthew Hittinger: I’ve been trying to find a way to articulate this for days now, but I think the one thing I will take away from AWP Denver, besides the wonderful people I met and new friends I made, is the remarkable energy at the Bloom gathering, seeing so many established and emerging queer writers in the same room, many of whom were meeting for the first time but had already discovered each other and each others’ work through Facebook and the internet. It left me feeling charged at our collective energy, and excited at the potential for what we might accomplish in the future, both in our dialogue between the different generations of queer writers present, but also in the work to be written by the emerging writers.

Joan Larkin: Michael Nava read from the manuscript of a historical novel that promises to be an illumination.

Randall Mann: I think perhaps the most memorable thing from AWP was David Trinidad’s lovely and moving reading from the anthology Persistent Voices, and the way so many of his memories of the lost were anchored by the meals he once shared with them, a detail as celebratory and crushingly sad as this anthology in which these poets finally rest, yet live on.

Miguel Murphy: I remember jaywalking lost at night with Doug Powell through downtown Denver’s abandoned glitter. I remember Jean Valentine smiling at the risingfalling seas as she got a standing ovation. I remember kind David Trinidad in the Wrangler kept me company, sweetsadly reminiscing about his missing puppy.

Stacey Waite: Jericho Brown’s warm handshake, his voice smooth like a trumpet. I remember standing with other boy queers at the Queering Desire panel, and thinking of us all as Maureen Seaton’s boys. I remember dry and high Denver making Chapstick a necessity. I remember Ilya Kaminsky singing translations of Polina Barskova in the basement of the Marriott, his voice too rich and layered for any basement. And I remember a dream I had in which Aaron Smith and David Groff had a private jet, and Aaron kept arguing that the American flag be removed from the decal on the side of the plane, and David kept saying, “I know, I know but let’s at least fly it first.”

Brad Whitehurst: Running into my former high-school English teacher Ron Smith (straight, a poet published in the Southern Messenger Series with LSU Press). We spent two hours over drinks discussing poets we admire as well as my alma mater then — when I was an unformed, closeted adolescent — and now. We also shared war stories from the classroom. The encounter affirmed my more hopeful instinct that continuity can exist in our lives.

Photo Gallery: Double Click Images to See Larger

- Charles Flowers

- Jericho Brown, Aaron Smith, and Alex Dimitrov

- RJ GIbson and Matthew Hittinger

- Cyrus Cassells and Michael Brohman

- Randall Mann

- Joan Larkin, Saeed Jones, Elaine Sexton, David Groff, and David Trinidad