Fieldwork in Being a Brown Man

Author: Joe Jimenez

August 28, 2016

When I was six years old, my father called my mother’s step-mom and told her, “Come get them.” Back then, we lived in a trailer park in a small South Texas town near the Gulf, and what he meant was that he no longer wanted to be a husband or father, for my grandmother to come pick us up, my mother and my sister and brother and me, and to take us with her, take us back to her little yellow house across from the junkyard in her little cotton town. My grandmother drove the ten miles, and my mother cried, from what I remember, much of the ride back from her life with my father to the town from which she came. The trailer we left was a brown and beige unit behind an elementary school I attended, one of several, near a big ditch and a couple of open fields, with a monte, and a dirt road cutting through the middle of the two queues of trailers, caliche, mostly, that road, whose white dust rallied behind my father’s car as he sped off, after fighting my mother, after deciding. From a payphone at a Circle K near the trailer we lived in, my father called my grandmother.

Many times I’ve wondered what happened inside my father’s voice that morning when it pushed itself out of his throat, how it skid across his fat tongue like a slug or maybe like a hog, crawling its way across a hot field, a dampness, how it left its hoof prints in everything it touched, the voice scraping against his teeth and spit and doing what it needed to do, tusks and slobber and spines, regardless. I have not seen my father in so many years that I have forgotten what he sounds like, yet I imagine his voice that morning when he gave up on us was firm, resolute, because he would have practiced this moment, this small speech. For as long as I remember, I have promised myself to be nothing like my father.

Arriving at my grandmother’s house, I sat in the car while my mother went inside and cried. The sky was blue, and I could hear my mother’s gasps and grunting as my grandmother hushed the ignition and said, “Your father doesn’t want y’all anymore. Y’all are gonna live here with me.” She held my hand when she said this.

Flat and faultless, my grandmother’s face was stern, like a piece of land that had worked too much, that was being asked, still, for more.

In the backseat, my little sister began to cry. She was three. I love my sister.

My brother, a baby, sat very still beside her and drooled, his thumbs, tiny and stub-like, clipping themselves to my sister’s little leg with a concern only a baby might summon.

Across the street, tall yellow grasses consumed an overgrown lot. Junk cars and demolished ones, their bodies so smashed they barely were cars anymore.

For a long while we sat in that car in my grandmother’s rock driveway, surrounded by trees and a pink church whose bell monotonously sung its daily noon hymn. And because it happened so long ago, and perhaps because I don’t much like considering this event, I don’t recall what I did except that my heart simply wanted to beat, my heart simply wanted this moment to end, to never happen again, and I wanted to move on, for my sister and brother to be safe and to feel loved and to laugh again and for my mother, whose heart was broken that morning and must have been so fearful of what was to come, to stop hurting. I do remember we sat in the car listening to an old country song, the name of which is unimportant, until my mother’s deep sobs subsided, and as my grandmother carried my brother and led my sister by the hand into her house, she handed me the keys, and I knew to unpack the trunk, to drag the bloated trash bags with our clothes and a few toys up my grandmother’s cement steps.

The truth is I don’t know what it is like to be a father. I will never have children of my own. I teach twelfth grade, and I am surrounded by kids most days, good days, nearly all of them, but I am not a father, even if I am old enough to be one, even if I am the closest some students have to one. Over these years, often, I have behaved paternally, with my brother and sister and mother, caring for them, comforting and providing for them, and also, and perhaps more pronouncedly, for the three men I have loved. Yes, I once believed I could save a man from the demons of the world, from himself. And no, still, I do not know what it is to be a father. My partner knows—he has two sons. I have four dogs, had—we lost little Amber last summer to breast cancer. Yes, dogs get breast cancer. Who knew? I certainly didn’t know I should worry about cancer in her mammary chain afflicting her. And so, I do know what it is like to feel fiercely attached to someone or something, in the case of dogs, in the cases of people I’ve loved, to fear intensely, profoundly, the idea of losing them or having harm befall them. Accordingly, I know what it’s like to worry I cannot save someone or give my loved ones better than life has decided they deserve. In this, I don’t know what was going through my father’s mind when he determined in May of 1980, just as I completed first-grade, that it was best to leave us—what goes through any man’s mind when he dumps his family, runs off to another, seemingly better life?

Growing up without a father, I worried there were things I should know how to do. I was a boy. In South Texas, as in other places in America, in the world, there are things boys are expected to know how to do—punishments ensue, fierce judgments handed out for those who do not know. But, I didn’t learn how to change a spare tire, for example, until my first lover taught me to do so when his car took a flat near La Puente, California, near LA, and along the side of the 90 freeway, with a cloudless sky and SUVs zooming by, I learned, not because a man showed me but because I had to. Up until the age of twenty-two, I didn’t know the difference between a crowbar and a plumber’s wrench, though I looked them up in a book one night in another man’s house, a working man whose mouth tasted like menthols and kissed with his hands scratching the stubble on my scalp, a small notable lesson in things men are supposed to know, granted by lamplight and an older man’s after-love snoring. In no way do I still believe these things necessary to know, not essential, in any way, not fundamental, in order to be a man, much less a good one, but for a long while I have convinced myself that knowing those things once denied me can help.

In school, there were things I could learn like how to make a diamond out of my hands when I catch a football or how to position my feet and angle my body, tilt myself to the right, just enough, at the last moment, when there was a baserunner on second and I wanted to guide a baseball from home plate into right field. I knew these things because coaches told me; coaches were like fathers to me, the closest thing, a few of them, in particular. A boy very eager to please his coaches, I listened well and executed what they asked of me as best I could. But there are other things I very badly wanted to know how to do, and because no one—not my absent father nor my uncles who didn’t care, not my mom’s string of tough-lipped, fast-fisted boyfriends—was willing to show me.

I wanted to know how to stand up for myself, without having to throw chingazos.

I wanted to know how to stir other people to listen to me when I had something necessary and important-to-me to say, without being a dick, without yelling or laying down threats.

I wanted to ask my father about his tattoo, the formidable black cross holding a scroll that stretched across his enormous biceps. How to make myself, to pack muscle on my bones, on the bones of my ideas, and on my voice, on the hooks that hung from my arms like hands—this is what I wanted, a knowledge of who I was and who I was becoming, and just as important, how and why this was happening to me.

And it’s here, in the fieldwork of questions of becoming, of being a brown man, of being brown in a world that doesn’t always embrace brownness, where I learned to hanker, to want questions if not answers, this heaving push that slingshot my voice over the fence of my tongue and all its beliefs about what I should say as a brown boy from a family most considered trashy and fucked-up and poor, as a queer man who has a diamond I want to make with the stories I carry in my fists.

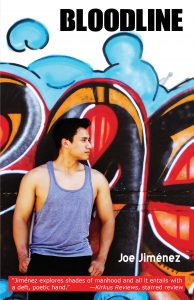

And so, I wrote a novel about a boy with no father. Published by Arte Público Press in May, Bloodline tells of the story of Abram, a seventeen-year-old with a penchant for fighting, with questions about the man he’s becoming, with a budding love in his heart for a smart, red-haired girl from school named Ophelia. I chose to write this YA novel in second person, because, like others, I need stories that serve as direct addresses, as engagements with young brown readers, with readers and thinkers who care about what happens to poor and working boys of color and how we might undo thinking and practices around toxic masculinities. When I started writing the novel Bloodline, I began with just this question: Does a boy need a father in order to become a good man? There are myriad ways to be men, both conscious and unconscious, and seeing the manners in which other masculinities are performed offers neurons and muscles the magic of doing and of being. In this novel, I echo Hamlet and tell the story of Abram, who fears his anger is the consequence of coming from a line of men who, like him, fight and distrust and want to break things because too often life seems wicked and unfair. Abram’s grandmother, Getrudis, along with her partner, Becky, raise Abram and disagree on the notion that Abram’s uncle Claudio, regardless of his troubled past, regardless of his dangerous ideas about manhood, should come back into the house so that he can teach the boy “how to be a man.”

And so, I wrote a novel about a boy with no father. Published by Arte Público Press in May, Bloodline tells of the story of Abram, a seventeen-year-old with a penchant for fighting, with questions about the man he’s becoming, with a budding love in his heart for a smart, red-haired girl from school named Ophelia. I chose to write this YA novel in second person, because, like others, I need stories that serve as direct addresses, as engagements with young brown readers, with readers and thinkers who care about what happens to poor and working boys of color and how we might undo thinking and practices around toxic masculinities. When I started writing the novel Bloodline, I began with just this question: Does a boy need a father in order to become a good man? There are myriad ways to be men, both conscious and unconscious, and seeing the manners in which other masculinities are performed offers neurons and muscles the magic of doing and of being. In this novel, I echo Hamlet and tell the story of Abram, who fears his anger is the consequence of coming from a line of men who, like him, fight and distrust and want to break things because too often life seems wicked and unfair. Abram’s grandmother, Getrudis, along with her partner, Becky, raise Abram and disagree on the notion that Abram’s uncle Claudio, regardless of his troubled past, regardless of his dangerous ideas about manhood, should come back into the house so that he can teach the boy “how to be a man.”

The truth is I don’t expect this novel to answer that question necessarily, and I don’t know that I’ve found one singular answer to it in my own life, but instead, and perhaps more necessarily, I needed the story of Abram to kindle questions in my readers, particularly young male readers, young male Latino readers. If you don’t have a father in your life, or if the only male figures in your life are fuck-ups, to whom do you turn to learn things you want to know? Every day, how are women teaching boys to become men? More precisely, in the story I am telling, how do queer women guide boys to become men? And in this, how is it we unlearn the toxicities of masculinities that seek to dominate, control, dictate, and crush? I believe these questions matter not only to people like the ones for whom I have written this novel but to people who care about what the world does to boys and what boys do to others, to themselves. In this, Bloodline offers an opportunity to interrogate our notions of masculinity, a Latino masculinity that wears its class and race and sexualities like a chestful of irremovable placas, a Latino masculinity that all too often is reduced to a simplistic and stereotyped hyper-machismo but that speaks so many more potent possibilities.