The Queerness of Robots

Author: Margaret Rhee

July 25, 2018

“The future is queerness’s domain.”

-Jose Munoz

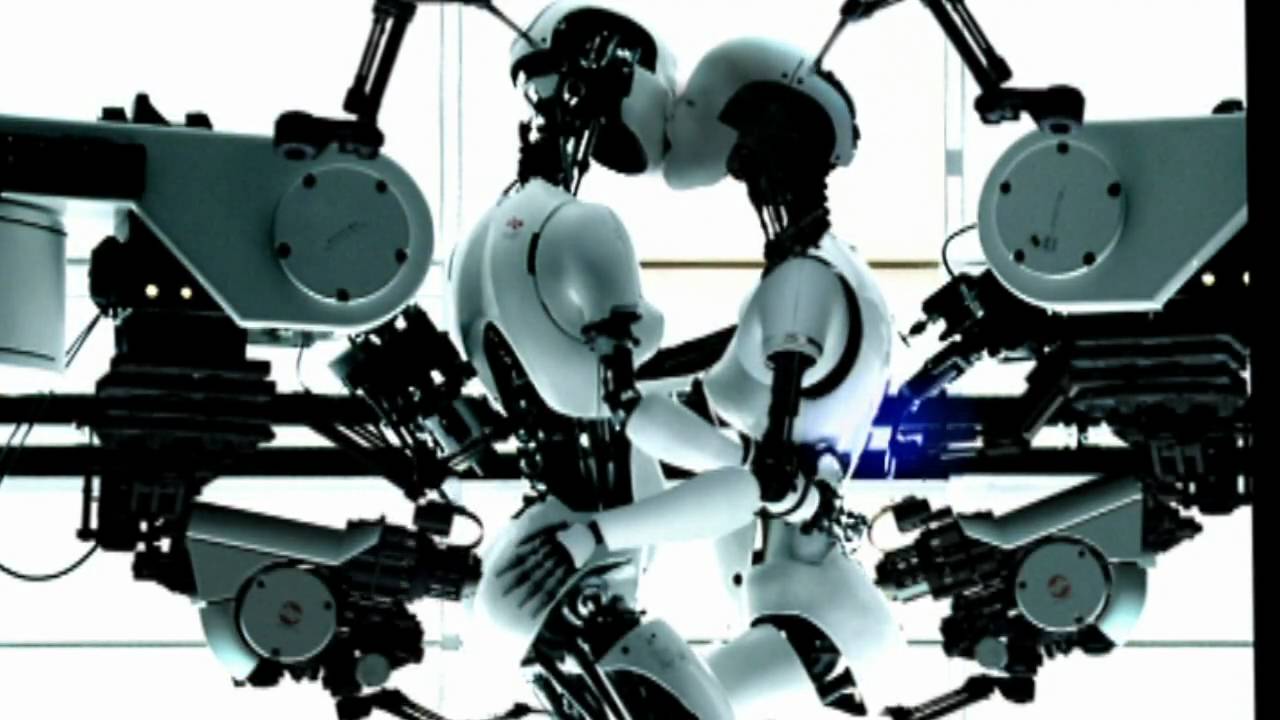

The first time I watched Björk’s music video “All Full of Love,” I couldn’t help but think these robots are queer. The video begins with a close-up on a robot with musician Björk’s features being assembled by the rhythm of large mechanical arms. Later on, the robot meets another identical robot, as the two passionately and tenderly kiss one another, as mechanical arms above continue to assemble the robots. Within an ethereal setting from the future, the two robots are feminine but genderless, and they express queer intimacies in their erotic embrace. Uncannily, the song about love evokes how the future is indeed, as queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz writes, can be “queerness’s domain.” When I first watched the video, it reminded me of the various potentiality that queerness could imbricate with technology.

Not only does Björk’s robots depict queerness in their genderless robotics, but it also connects with famed gay computer scientist Alan Turing’s ideas on artificial intelligence and gender. For example, in his 1950 article “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” Turing introduces his “imitation game” of artificial intelligence by asking if one could discern between a man or a woman. Later on in the article, Turing asks whether in the “imitation game,” if one can determine between a computer and a human. If one can’t, then the machine is artificially intelligent. While gender initially frames the “imitation game,” this gendered connection is largely obscured in the history of computing. Turing was open about his attraction to other men, and in 1952 penalized for his same – sex desires (and posthumously pardoned in 2013). Like Bjork’s genderless queer robots, Turing’s sexuality speaks to the connection of our Siris of today and queer history.

This is somewhat of a winding way to reflect on why I turned to robots to contemplate queerness. My first poetry book, Love, Robot is a collection of robot love poems, set in a world where humans and robots fall in and out of love. As a collection that gestures back to Alan Turing’s sexuality and writing on machines, and inspired by music, my poetry collection is an attempt to depict a future world where boundaries between robots and humans is transgressed. Writing about this robotic world of sexual and romantic subversion helped me articulate a futuristic queer logics. Queerness cuts across binaristic thinking, and offers new poetic articulations. While the poems have no explicitly queer content, I see these robot love poems as queer. If we can think of queerness as the embracing of, and celebration of non-normativity, science fiction can also offer new queer ways of thinking. In this ill-fitting heterosexist world, rethinking robots as queer, I would argue, may act as a suture to a non-normativie prism that radically imagines otherwise. While not explicitly, robot love poems are about queerness too.

A few years ago, I, along other queer and trans poets–Meg Day, Oliver Bendorf, Ching-In Chen, Tamiko Beyer, and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha–co-edited glitter tongue, an online journal of queer and trans love poetry (2012). Based on our collective and informal digital conversations about queer and trans love, we co-edited the digital anthology in order to express the complexity of the love explicitly through a queer poetry lens. In many ways, I feel my love poem for our anthology helped lead me to my collection of robot love poems. While I still write overtly queer poetry, and theory, when I began writing science fiction poetry, I began to realize that I was able to articulate ideas about queerness and love through this language of robots in a braver way. The language of the future, helped me express queer intimacies and sentiments not possible to explain within the languages of a overwhelmingly heterosexist world.

When I released Love, Robot in November, I wasn’t sure if people would pick up the queer learnings or references. But I felt it didn’t matter. I hoped the poetry would provide a different kind of orientation to queerness, one that was not explicit. To my pleasant surprise, when the book was reviewed, it was described in terms of queerness. The collection includes various forms of poetry, including narrative poetry, sonnets, as well as technological forms such as algorithms, and chatscripts. In particular, the Chicago Review of Books pointed out a section I wrote, “Out for Robots,” which was based on real life same-same marriage canvassing scripts. When I came across the canvassing scripts, at the time of finishing the collection, I felt it would provide an interesting way to explore the limits of political and sexual language. How to convince someone to support two people’s right to marry and love?

The two poems I wrote, “Listen/Acknowledge” and “Street/Rap,” draw upon same sex marriage canvassing scripts to describe this robot and human world. At the time I was writing the book, same sex marriage was not legal in all states from 2013 – 2015. These poems draw upon the canvassing language utilized in these campaigns. Political canvassing is the direct contact activists have with people. Typically, canvassers approach people walking down a street, or they knock on doors. They are commonly young people with bright T-shirts, a clipboard, and a ready smile to persuade. The scripts in political canvassing is highly structured. The canvasser have their dialogue ready for their targets of persuasion. More recently, there have been studies that deep conversations with canvassers can change the opinions of LGBTQ rights. In part, because the face to face interaction is a conversation that most people across political divides can never have.

In the poems based on these same sex canvassing scripts, I wanted to create a different world based on robots and humans, entitled the “Out for Robots” campaign. This science fictional campaign centered on helping “35 states that do not recognize marriage equality” between humans and robots. In large part, I not only wanted to make parallels between the same sex marriage and robot/human marriage, but I wanted to explore the politics and poetics of persuasion: How to convince someone to accept non-normative love?

While conversation can be one way to change minds on homophobia and transphobia; another powerful avenue of queer acceptance is through literature and art. For example, queer films and television have been powerful to depict queer individuals humanly, such as the study “Gay On-Screen,” Bond & Compton (2015) reveals with media interactions, heterosexual attitudes towards homosexuals were more supportive. Moreover, literature such as fiction and poetry have also been powerful vehicles of change. In another study of college age students, artistic texts by and about gays, lesbians, and bisexuals performed at festivals “significantly reduced homophobic attitudes.” Additionally, the canvassing poems asks the question of could a poem be utilized to promote acceptance; what is the difference between a canvassing script and a poem?

Moreover, “Listen/Acknowledge” and “Street/Rap,” also aims to question same sex marriage. As a queer identified person, while I believe marriage is an important issue, I also believe in the important critique that same-sex marriage should not be the sole priority issue for the LGBT community. As queer scholars such as Jasbir Puar have formatively argued, same sex marriage can be upheld as a strategy of “homonormativity,” which legitimizes queerness within definitions of heterosexuality. Individuals such as transgender people or poor people of color without access to marriage may be left out of these campaigns. I hoped the poems drawn from same sex marriage canvassing could complicate notions of acceptance through robots as well. Even with the legislation around same sex marriage, homophobia and transphobia still exists. The numbers of trans women of color and the violence to their lives, for a pressing example, is staggeringly high and should be a priority within queer movements. Literature is one way we can combat dehumanization.

Literature is another way to insist on a queer future in a world that often does not allow us to have one. In 2012, when we decided to create glitter tongue, we did so as a response to the staggering numbers of queer youth who committed suicide without hope for a future. We wanted to insist that queers had a future, and a future with love. In many ways, my robot love poems are a similar kind of gesture. Robots is one way we can move towards the blue light. Towards a back door to queer horizons. Once, someone told me that when you release a book, it belongs to the hands of the reader, and you no longer have control over it. And they, the reader, can read it any which way they want. Who would think robots are queer? Yet, perhaps that possibility and surprise is the pleasure. The gesture to robots is just one of the many ways our queer futures can be made.