On Plague and the Queer Art of Absurdist History: Larry Kramer’s ‘The American People’

Author: Dan Lopez

May 19, 2015

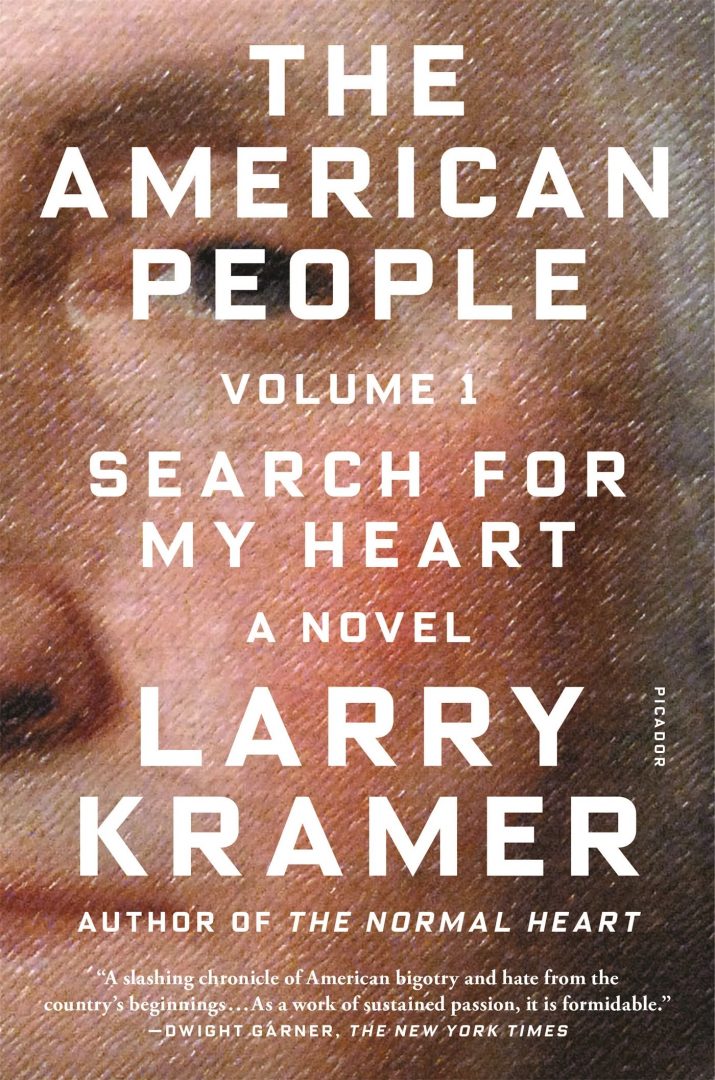

Larry Kramer’s new behemoth of a novel, The American People, opens in the primordial Everglades. “Look at a map,” Kramer writes. “Florida is America’s penis and the Everglades is its rectum and the Gulf of Mexico is what we pissed and shat into.” Right from the beginning it’s clear that this is a book with an agenda. Forty years in the making, Kramer’s text aspires to history more so than to fiction—though it’s a peculiar history, to be sure, one that reads like a True Hollywood Story or a legend.

Alternate histories of the kind Kramer presents here are typically Utopian in purpose if necessarily exclusionary in scope, promoting one subject at the expense of many (though the same can be said of most established histories, too). While Kramer’s text does insist on a very clear point of view it conjures a bizarre Utopia. Warring tribes of monkeys—the first American people, we’re told—introduce “The Underlying Condition” into our long genetic stream through acts of cannibalism and rape. The UC will wend its way through history, a silent (though Kramer does give it its own voice in the book) witness-participant to every plague the species endures over the long arc of history, all the while accreting in strength in preparation to take center stage. Kramer, of course, is writing about AIDS—an alternate history of AIDS, and, yes, one that evokes an odd Utopia when you consider the role HIV/AIDS played in catalyzing the contemporary gay rights movement. The book is as angry as one would expect a tome on plague to be from the pen of a survivor who has spent the better part of a life advocating for the health (physical and political) and visibility of his people.

Though often moving, AIDS narratives have matured as a form. Had The American People lingered over that familiar territory it would’ve been easy to dismiss Kramer as an elder statesman returning to a diminished well, but it doesn’t. It has broader historical ambitions. Kramer’s cosmology lacks sacred cows. Long an advocate for unearthing hidden gay history, Kramer, here, starts from a place of assumed queerness and shows little restraint in illustrating his point. George Washington, the inhabitants of Jamestown, large swathes of Native Americans, Abraham Lincoln—all these American people are exposed as gay and depicted expressing that gayness physically. There’s little point in contesting (or validating) Kramer’s assertions, however. Whether or not he’s telling the truth is secondary to a deeper aim. As much as The American People purports to historical authenticity, Kramer’s tome is primarily a masterpiece of the queer art of legend making, a natural byproduct of our occluded historical visibility. In the absence of a documented history, what avenue is left a people? How do they chronicle themselves, their contributions, and their accomplishments? In a sense, The American People provides an answer to those questions: We fiercely defend what is known and embellish where needed to create a coherent narrative.

Writing 90 miles from “America’s penis,” Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas’ The Color of Summer conjures a similar absurdist alternate history. An advocate for queer people in his own right, Arenas spent the majority of his life resisting the dual oppression of homophobia and state control in totalitarian Cuba before eventually fleeing to the United States where he would promptly die of AIDS. Best known Stateside for his memoir, Before Night Falls, it’s in his “pentagonia,” a five part “secret history” of revolutionary Cuba, of which The Color of Summer is part, that his grandiloquent surrealist vision finds its truest expression. Following the death of “Fifo,” Arenas’ stand-in for Castro, the people of the newly freed Cuba struggle over where to take their suddenly directionless island. Some argue for the United States because of its proximity and economic stability, while others:

insisted even more determinedly that they should turn the bow toward Spain, “because that’s where we all came from, and this is no time to be learning a foreign language.” Then a leader of the black population said in a powerful voice that if they were going to sail to any continent it ought to be the continent of Africa, because the Carnival itself, whose drumbeats had freed them from their chains, was living proof of the African roots of the Cuban people—and turning theory into practice, he dipped his hands into the sea and began to turn the Island toward the Cape of Good Hope.

The marooned islanders argue like this for a long while. Many other voices chime in, insisting on destinations spread across the globe. Arenas is, in part, mocking the ardent outrage of a liberal identity politics that insists on primacy in all discourse (as vocal in ’90s Cuba as it is today on social media Stateside), but in his own cheeky way he’s also drawing attention to the weakness of a community that lacks a clear shared history. For all his faults, Fifo and his regime provided Arenas’ Cuba with that shared history. If nothing else, there was a unity against oppression. Now cast out in a post-revolution world that desires to put some distance between themselves and a painful past, the Cubans desperately cling to whatever unifying element is at hand—a shared language for those advocating Spain, a shared cultural expression for the proponents of Africa. Like Kramer, Arenas speaks to the universality of a silenced people’s need for history, and, like Kramer, he’s forced to manufacture and embellish in order to provide it.

Desperation permeates Kramer’s book. Whereas Arenas’ absurdist take gestures toward the danger of a historyless society, Kramer spends nearly 800 pages strong-arming a queer history into place, writing, in the voice of one character, “‘I am annoyed to note that you believe that almost everybody is either a homosexual or a repressed homosexual or a homophobe. Is this what your history of The American People is to be?… How dare you be such a usurper.” Whether or not George Washington was queer, whether or not Lincoln sucked cock, isn’t the point. What Kramer, somebody who was around before, during, and after the plague years—and who often feared he’d perish before completing his magnum opus—is ideally positioned to show is the tragedy of our lost heritage, an oral history decimated by the scores of citizens cut down by AIDS. We lost an entire generation in the ’80s and the ’90s, and with them went countless stories and facts (and, no doubt, stories that were too good not to be considered facts). Watching the way memes of gay culture spread through the community today (think of anything you’ve picked up while watching Rupaul’s Drag Race and then think of how many people you’ve shared it with), it’s not hard to imagine the scope of what we’ve lost. The American People is an elegy for our community. It’s a grand novel attempting to imagine a history to replace the one we lost during the ink black days of our recent past. If nothing else, reading Kramer is an invitation to reflect on the ongoing tragedy of AIDS. Even as the advent of PrEP and the ubiquity of condoms in our public gathering spaces make expressing our sexuality safer than ever, the aftermath of what we lost will stay with us for a long time, perhaps forever. One senses in Kramer an urgent need to salvage what we still can, while we still can.

While The American People inspires us to record and bear witness, it also serves as a call-to-action to diversify. For the past thirty years we’ve been a society dominated by single foci: first AIDS, now marriage equality. But queerness is much more than either of those things. Our identity is broad; we contain multitudes. As Kramer’s American people make their way through the 21st century, it’s important to remember that, like Arenas’ Cuban people, we have a constituency of diversity. History is key to maintaining a strong cultural heritage, but history is more than queer presidents or drumbeats. History is an insistence on being remembered; the particulars are secondary. Both Kramer and Arenas understand that. History is also a powerful coalition-building tool. It allows us to find common ground with members of our community that we might otherwise perceive as foreign, and it allows us to work together to build stronger coalitions. Living with the aftermath of everything AIDS took from us, queer America in the early 21st century is a bit like Arenas’ directionless Cuba in the imagined days of the last century. Now more than ever we are in need of a common history to help unite us as we move forward. History is important, but as we endeavor to make a place for ourselves in the American saga we must document and celebrate our scope as well, lest we lose the very things worth remembering.

The American People People: Volume 1

Search for My Heart: A Novel

By Larry Kramer

Farrar Straus and Giroux

Hardcover, 9780374104399, 800 pp.

April 2015