Dancing with Audre Lorde: A Lesbian Memory

Author: Victoria Brownworth

February 22, 2015

1.

There are moments in one’s life that are indelible. Some are traumatic, some are fantastic, some are sweet, some take us to the very edge of darkness. Some are small, yet indescribable and they remain with us, seared in our consciousness. There is an inchoate beauty to all these moments, these memories, because for whatever reason they have stayed with us–no matter how seemingly minor the event–there is a meaning beyond memory that is a vivid, vital piece to the puzzle that comprises our lives.

February is, of course, Black History Month. I was born in February, as was Audre Lorde. It is for black lesbians I reach out in February, staving off the erasure that is fast encroaching upon all lesbians. I am, as Adrienne Rich wrote in Diving Into the Wreck, forever transliterating from “the book of myths.” I am always recalling that

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

Audre Lorde was one of those treasures of our lost feminist and lesbian history. Audre Lorde, who will never leave my consciousness, Audre Lorde, who said, in A Litany for Survival, the documentary about her life by African American film makers Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson, “What I leave behind has a life of its own….I’ve said this about poetry; I’ve said it about children. Well, in a sense I’m saying it about the very artifact of who I have been.”

As Rich wrote: “the thing I came for:/the wreck and not the story of the wreck

/the thing itself and not the myth”

The essence of Audre Lorde, the little piece I took away with me when I met her, like a beautiful shiny object, like a talisman, like a life-preserver.

That.

Her.

Audre Lorde.

2.

I was wearing winter white the night I danced with Audre Lorde.That’s a color–winter white.A kind of vellum-starting-to-fade, just off-white kind of white. An off-white wool skirt, an off-white sweater with lace along the décolleté neckline, a winter white coat. If I had fallen in a snowbank on the streets of Manhattan on my way to the dinner party, I likely wouldn’t have been found until spring.

I was poor in those days, but always trying to look like I had more than I did–a trick I’d been taught before I could read by my mother who had grown up in what she once and only once described to me as “shameful” poverty. The poverty in which I was raised was confusing as well as shaming, but she never saw it that way. Because she taught me about passing.

I’d learned how to shop for “good” clothes as a child on Saturday mornings in the local thrift shop, tutored by my mother, whose penniless youth was devoid of such privilege as the used “good” clothes of others. So that night in Manhattan I arrived at the party in my understated elegance passing for money, because in those days I was still passing, always passing.

A 20something writer fresh out of the domestic Peace Corps trying to make it in the city of a million nascent writers, I yearned to be like the women in that lush West Side apartment. I was so eager, so propelled by the need to do and be, to change whatever I could. To make a mark, an indelible mark. I took every assignment. Went anywhere I was asked to go. Slept around. A lot. Tried on experience after experience like other women my age were trying on jeans in smart uptown shops to wear to the clubs.

That night, at that party, I was by decades the youngest woman there. I was out of my depth, but I was an enfant terrible, and among enfants terribles, confident that once in the door, I would have some tidbit to offer. Even if that tidbit was only my oh-so-impressionable youth and my surprisingly good stories for someone still so young.

This was an intimate gathering of about two dozen feminist writers and artists. I was there by luck and fortune and the perfect alignment of the stars–the plus one of an art historian who had a massive crush on me and who in turn was close friends with the woman giving the party, a noted New York artist. The art historian was showing me off, like a scene out of Marilyn Hacker’s Love, Death and the Changing of the Seasons, where the middle aged lesbian is so deeply and irrevocably infatuated with the 20something who has no moorings.

I had no moorings. I was looking for depths to plumb in the words of these women who had only ever been required readings for me.

I was given to awe in those days (truth be told, I still am; I’ve never learned to be jaded) and it was an awe-inspiring night. I was in the same room with Audre Lorde and Phyllis Chesler and Betty Dodson, among others, and it wasn’t a classroom or a lecture, but an amazing two-story apartment in New York City with a three-quarter view and oh did it take my breath away just being there in that rarified atmosphere, a poor girl in the lap of lesbian and feminist luxury, both literal and intellectual.

I cannot remember eating at that sit-down dinner. I just remember the table and the conversation and the intensity of being part of it, of being part of a conversation with women I had studied in school, from whom I had, through their books and work, learned feminism. Women I revered like I had once, as a girl in Catholic school, revered the female saints.

There was wine, a lot of it, and I do remember the wine. Heady, redolent. I think we were all a little drunk. Who wouldn’t be, surrounded by such a wealth of feminist iconography?

After dinner, where I felt I should have been taking notes on one of my little reporter’s note pads, we all congregated in the living room. There was music–I couldn’t tell you what was playing. Something danceable from the early 1980s. I was half-standing, half-sitting on the arm of a sofa, a glass of wine in my hand, trying to imagine how I could ask one of the artists I had met to have drinks with me another time, when I had come with someone else.

And then there was Audre, right in front of me, asking me to dance. Audre Lorde. Icon. Audre Lorde, whose work emanated the kind of raw fire I was wanted to write myself.

I can’t explain how it felt to be in her arms. It’s easy to say it was a rush, but it was more than that. Because I felt then and in the 30 years since, that she was transmitting something to me. Something visceral and deep and essential–as in, the essence of. The essence of her, of what she knew and was. It stuck to me, whatever she had poured out onto me as she held me and talked and laughed in my ear and moved me around the small bit of open floor with her vivaciousness and so-much-Audre-ness.

A romance heroine would say, “I was a willing captive in her arms.”

And I was. Willing. Captive. Captivated. Mesmerized.

Whatever it was about her stuck to me–her scent, her realness, her voice, her laugh. It stuck to my winter white and my eagerness and my unsureness beneath the bravado of youthful prettiness.

It stuck to my heart.

How did I know then, when she finally let me go, that it was a dance that would change my life forever?

3.

The night I danced with Audre Lorde she was already missing a breast, having had a mastectomy in 1979, when she’d been diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer was a battle she would fight the rest of her life and it was cancer in her liver that would kill her, eventually, in 1992, exactly three months shy of her 59th birthday.

In the early 1980s, women weren’t having reconstructive surgery the way they do now. There were no Angelina Jolie’s having their breasts opened up and scraped out and restructured to avoid the empty space and fat angry scar where their breast had once been.

When I was in college, I had a job in an office where the receptionist, a strikingly beautiful woman in perhaps her late 50s, early 60s, had had a mastectomy. It was the buzz in the office, but not talked about except secretly. But one day as I stood at her desk and she leaned forward for something, the V of her dress puffed out and I saw the prosthesis on the left side where her breast should have been. It was a glimpse, a nanosecond. Her head was bent over her work and she didn’t see me seeing her. But it shocked me.

The missing limb of femaleness.

Audre didn’t have a prosthetic. She didn’t believe in them. She had a breast and she had a blank space where a breast had once been. She was a true Amazon warrior, with her single breast and her fuck-you attitude about it.

I had said nothing memorable while we danced, but she had said something.

In The Cancer Journals, which are excerpted in my own book, Coming Out of Cancer: Writings from the Lesbian Cancer Epidemic, Lorde writes, “I would lie if I did not also speak of loss. Any amputation is a physical and psychic reality that must be integrated into a new sense of self. The absence of my breast is a recurrent sadness, but certainly not one that dominates my life.”

She also wrote in her essay,“Breast Cancer: Power vs. Prosthesis” in The Cancer Journals, “I also began to feel that in the process of losing a breast I had become a whole person.”

Was that what she had told me?

I would read that later, as I lay in a hospital bed at 26, my own breast cancer diagnosis and its consequences looming before me.

Interviewed for an article on breast cancer for the New York Times the year before her death, Lorde, who had chosen not to wear a prosthesis for feminist philosophical and political reasons, said, “When other one-breasted women hide behind the mask of prosthesis or reconstruction, I find little support in the broader female environment for my rejection for what feels like a cosmetic sham. The social and economic discrimination practiced against women who have breast cancer is not diminished by pretending that mastectomies do not exist.”

She taught me this–about sham, about pretense–that night at the party where I was passing for everything and she was refuting passing.

She taught me, in the time it took to sweep me around the floor, that artifice isn’t just meaningless, it is damaging. Artifice is a facade that subverts and undermines the truth, that hides what is raw and awful and real, and in doing so, allows the wounds to fester and infect us all.

As Lorde wrote in The Cancer Journals, “Imposed silence about any area of our lives is a tool for separation and powerlessness.”

She exuded power.

Maybe that is what stuck to me that night–her belief that women, especially lesbians, had power, if they just seized it.

In her poem, “Power,” Lorde begins:

The difference between poetry and rhetoric

is being ready to kill

yourself

instead of your children.

Later in that poem she explains:

I have not been able to touch the destruction

within me.

But unless I learn to use

the difference between poetry and rhetoric

my power too will run corrupt as poisonous mold

As Lorde wrote in her famous 1984 essay, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” which appeared in her collection Sister Outsider, power was a relative term that was often used with a large dollop of moral relativism. Power was in many ways subjective and objective.

That title is often used as a quote, but almost always out of the context within which she wrote it, which is about how the connection to men and patriarchy privileges people, including women. In discussing her perspective on racism within feminism–an issue still roiling today, three decades later–Lorde situated what she called the “unrecognized dependence on the patriarchy.”

We aren’t allowed to use the term “patriarchy” anymore–doing so calls down the label of radical feminism, which is considered déclassé within liberal (still mostly white and wholly straight) feminism and within the LGBT community as well. But Lorde was a radical feminist intent on the dismantling of the patriarchy and her polemic in the essay is clear: there are strata within the class women and ignoring that, whether with regard to race or sexual orientation–whiteness or heterosexuality as opposed to color or lesbianism–reliance on the patriarchy was solidified. There could be no place for lesbians or women of color within a feminism that was straight and white and ignored the subjugation of not just the class women, but the subjugations within the class women.

Straight women, white women were dependent on the patriarchy to maintain their own limited power which was linked to male privilege. Refusal to accept that reality, Lorde argued, made straight feminists and white feminists “agents of oppression.”

Thirty years later that essay has been read less and discussed more as just its title, not its substance.

Audre Lorde was a lesbian. A radical feminist. A one-breasted Amazon speaking from a state of, she wrote after that essay, fury. “What you hear in my voice is fury, not suffering. Anger, not moral authority.”

Power, not privilege.

Yet the longest romantic relationship of Lorde’s life was with Frances Clayton, a white academic with whom she was involved from 1968 to 1989 and with whom she raised her children. Lorde met Clayton when she was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi.

Lorde said some feminists declared she hated white women, but I saw her that night at the party. She loved women, all women. She loved Frances. She loved me, for that brief time, that night, when we were dancing.

Audre Lorde was a warrior, but she was also a lover. Her essay, “Uses of the Erotic” should be read over and over again. She situates female-centered sexuality, lesbianism, women’s sexual energy and power outside of male dominance, outside of the penis, outside of the male gaze, outside of all the things that have straitened (and straightened) women for millennia.

She writes,

There are many kinds of power, used and unused, acknowledged or otherwise. The erotic is a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling. In order to perpetuate itself, every oppression must corrupt or distort those various sources of power within the culture of the oppressed that can provide energy for change. For women, this has meant a suppression of the erotic as a considered source of power and information within our lives.

She also wrote, “Part of the lesbian consciousness is an absolute recognition of the erotic within our lives and, taking that a step further, dealing with the erotic not only in sexual terms.”

As Lorde describes the erotic within herself, it is almost palpable–it is, indeed, power: “When released from its intense and constrained pellet, it flows through and colors my life with a kind of energy that heightens and sensitizes and strengthens all my experience.”

4.

One can read the details of Audre Lorde’s life in African-American academic and writer Alexis De Veaux’s comprehensive and to date, definitive, biography, “Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde, which won the Lambda Literary Award in 2005 for biography. The 500 page annotated biography with 16 pages of photographs explores all aspects of Lorde’s life and work, from her Harlem childhood during the Depression to her rise to celebrated author to her long cancer battle. It describes her brief marriage in the early 1960s which gave her two children, Elizabeth and Jonathon Rollins. It describes her 20 year relationship with Frances Clayton, the white feminist academic with whom she raised her children in, of all unlikely places, Staten Island. It describes her death.

Lorde lived in the U.S. for the majority of her life, but spent time in Germany in the mid to late 80s, working with the burgeoning Afro-German movement as well as seeking alternative medical treatment for her metastatic breast cancer which had spread to her liver. I had spoken to her when she was in Berlin and I in London for an interview in 1988. She was ill, but still surprisingly strong.

Her final three years were spent living in St. Croix with her last partner, Gloria I. Joseph.

According to De Veaux, in the year before her death, Lorde engaged in an African naming ceremony in which she took the African name “Gamba Adisa,” which means “warrior: she who makes her meaning clear.”

There has always been clarity in Lorde’s approach to writing and politics, feminism and lesbianism. At four she began to read as well as speak for the first time because she was born nearly blind. Her mother said Lorde didn’t like the way the Y looped below the other letters in her given name, Audrey. So she deleted it.

Naming–one’s self, one’s people, one’s ideas, one’s philosophy–would become a consistent theme throughout her writing. And even at the end of her life, she was still naming and re-naming herself. She was also naming and re-naming the place for herself to be.

In A Litany for Survival, Lorde says, “I grew up in Manhattan, I grew up in New York, I was born here. My parents were West Indian. My father was from Barbados, my mother from Grenada, and we were always told when we were growing up, that home was somewhere else. So no matter how bad it got here, this was not our home, you see. And somewhere there was this magical place that if we really did right, someday we’d go back.”

In a 1978 poem, “Harriet,” Lorde names the pain of never finding other places she was searching for:

And we were

Nappy girls quick as cuttlefish

Scurrying for cover

Trying to speak Trying to speak

Trying to speak

That pain in each others’ mouths

That pain was always just below the surface. Lorde said, “Let me tell you first about what it was like being a Black woman poet in the ’60s, from jump. It meant being invisible. It meant being really invisible. It meant being doubly invisible as a black feminist woman and it meant being triply invisible as a black lesbian and feminist.”

In 1980, with Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first U.S. publisher for women of color–making women of color visible.

Lorde was New York’s Poet Laureate from 1991 until her death, the author of more than a dozen books and countless essays and speeches. She was a voice from the late 1960s to her death for lesbians, for feminists, for black women worldwide.

Audre Lorde began “triply invisible.” But Audre Lorde made herself visible and in doing so, made others visible as well.

5.

I could write a book about Audre Lorde. About the feel of her hand on my waist, about the unrestrained laugh and the unrestrained surviving breast in her flowing clothes. I could write about the imprint of her work on me, on other lesbians, on other feminists. I could write about her language–the brisk cut-to-the-quick poetics of “Harriet” or the deeply philosophical essays in Sister Outsider that marked her as a singular academic.

I could explicate and deconstruct and document and reiterate. I could write about whose work she has influenced and especially how she influenced the rise of black feminism. Her books, her poems, her essays, her letters, her speeches, her performances–it is all a compelling, enticing, nothing-like-it piece of lesbian history, of feminist history, of black history.

I could write forever about how she was a lesbian and breathed the fire of lesbianism into feminism.

Audre Lorde described herself as “Black feminist lesbian poet warrior mother,” but repeatedly said that description was not enough to capture and hold her complete identity.

Audre Lorde would have been 81 last week. More than 20 years after her death, she is still revered, still missed, still ached for.

As Black History Month and our shared birthday month, draws to a close, I am remembering her that night, all bright and sparkling and just bursting with life.

I want you to see her, to envision how in a room full of dazzlingly bright lesbian and feminist lights, she shone oh-so-bright and I was so lucky as to received the gift of whatever it was she was exuding, that amazing energy that left people stirred and inspired.

Audre said one night at Hunter College,

I took who I was, and thought about who I wanted to be and what I wanted to do and did my best to bring those three things together. And that is perhaps the strongest thing I wanted to say to people. It’s not when you open and read something that I wrote. The power that you feel from it, doesn’t come from me. That’s a power that you own. The function of the words is to tick you in, ‘oh hey, I can feel like that’ and then to go out and do the things that make you feel like that more.

She was against awe, the kind of awe I had that night, the kind of awe I still have for her. She said,

You have got to go on. No, but you don’t need me. Don’t you understand? The me that you’re talking about you carry around inside yourselves. I have been trying to show you how to find that piece in yourselves because it exists. It is you. You have got to be able to touch that, to say the things, to invite, to court yourself out. And you can get together, you can do it for each other until you do it for yourselves. Don’t mythologize me

It’s impossible not to mythologize Audre Lorde. It’s impossible not to read her and underline nearly every word, every idea, every construct. It’s impossible not to quote her.

And so I remember her, memorialize her, put her in the place of lesbian icons of our collective history.

And I remind you of why she did everything she did. She said, “I write for those women who do not speak, for those who do not have a voice because they were so terrified, because we are taught to respect fear more than ourselves. We’ve been taught that silence would save us, but it won’t.”

She refused silence.

She gave us voice.

Her words, like that dance for me so many years ago, live on with a vibrancy and breadth we are so lucky to have, still, on the page, her, forever.

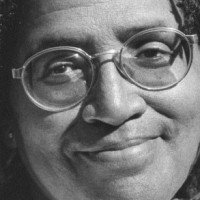

Photo: Audre Lorde via The Poetry Foundation