A Queer Take on James Franco’s ‘Straight James / Gay James’

Author: Jameson Fitzpatrick

January 16, 2016

Actor, director, artist, fiction writer and poet James Franco knows how to get a reaction. Perhaps the prevailing response to him remains a swooning and fanning-of-self on the part of many women and men alike, a holdover from his days as an undifferentiated teen idol. But as his resume has become more diverse and admittedly more impressive, an eyeroll seems just as likely. And in recent years, two groups of people in particular have become increasingly fed-up with (and increasingly hostile to) the celebrity provocateur: poets and gay men.

Both groups, it seems, share the same point of contention: that Franco, in his career as a poet, as in his ongoing joke/performance/trolling about the nature of his sexuality, has simply not earned his place. It should come as no surprise, then, that gay poets can get especially riled about Franco’s play with identity and “literary manspreading,” to borrow a phrase from Purvi Shah’s piece for Vida on the Michael Derrick Hudson yellowface controversy.

And yet Franco’s “queer public persona,” as he describes it in his latest poetry chapbook, Straight James / Gay James (Hansen Publishing Group), is meaningfully distinct from Hudson’s deceit, as it is from Rachel Dolezal’s, and from the cultural appropriation of Katy Perry and Iggy Azaela—all of whom I’ve witnessed white gay poets compare Franco to. Sexuality, unlike race or heritage, is understood to be fluid, and so, while queer culture certainly can be appropriated, I’d like to recognize and dismiss these easy comparisons at the outset. Franco isn’t trying to fool anyone so much as he seems to enjoy playing the fool.

Does the success of this public persona, then, of which his identification as a poet is most certainly a part (see: his affinity for gay poets Frank Bidart, Allen Ginsberg and Hart Crane), depend on the details of Franco’s private life? Is this a fair standard? And is the work even good enough to merit such consideration?

Not, per se, based on the quality of the poems this chapbook comprises. Largely, they resemble the work of a promising straight white male undergraduate poetry student—written late at night for, say, his second or third workshop, under the influence of the Beats, some Crane, and a pharmaceutical stimulant. (To be fair, Franco does, in fact, have an MFA in poetry from the well-regarded Warren Wilson low-residency program, an experience he writes about here.) As a poet, Franco is exactly the kind of guy who’d let a guy blow him once in college because he didn’t like the idea of being the kind of guy who wouldn’t. That guy is almost always good for a laugh though—and Franco’s sense of humor is undeniable.

The book begins in the voice of Disney’s Dumbo: “Dumb is me / As a young elephant I was shy, / From too much attention, So, speak I didn’t.”

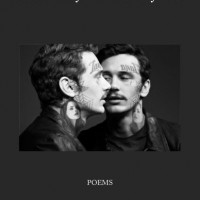

From this poem on, in which the speaker identifies himself as a “sinister clown, / With a smile painted / So thick / I looked mad-happy, always,” Straight James / Gay James concerns itself primarily with problems of persona. Indeed, the second poem is called “Mask”: “This mask is the face / Of Gucci, officially. // Because this mask / Has been branded” […] “He is the face / That drips with cum, / And glistens with pussy.” Franco concludes with a refusal to honor the boundary between his “outer Poster Boy and inner Beezle.” While they “don’t mix / In public,” “at night, / In sparkly light / They are but / One: me.” The cover photograph, which shows Franco either seductively inviting or skeptically considering a kiss with himself at a mirror, suggests this very union.

The poems within proceed in what has become, for Franco, unsurprising form: documenting his adventures driving around LA, hanging with his celebrity friends and celebrity brother, comparing himself (“The Witch King of the Hollywood Hills”) to Satan, and bedding an unidentified blonde woman whom he also compares to Satan (“Her shoulders like devil’s wings”).

Franco is most engaging when he seems his most self-aware, using his speakers to poke fun at both himself as author and the high drama of poetry itself:

I would make a Heaven of Hell

With a few well chosen accessories:

Black Jacket to hold my Red Wings,

Black Boots for my Cloven Hooves,Black Shades for Eyes that Burn.

This juxtaposition of cool leather luxury and traditional images of the devil (as well as the qualifier that the accessories are “well chosen”) charms—and yet, even as some of Franco’s strategic capitalization convinces, “Eyes that Burn,” the stalest formulation here, lets the rest of the line down.

The poems do affirm that Franco can put an outfit together; indeed, there are many “well chosen” descriptions of dress, all of which function as clear signifiers of particular cultural cues. In “Black Death,” a riff on Bidart’s “Herbert White” in which Franco “put[s] on the mask of” California serial killer Richard Ramirez, he chillingly itemizes his uniform to communicate that “it’s on,” so to speak:

AC/DC Baseball cap: On. Avia high tops:

On. Black trench coat: On.

And yet the violence of this short poem, which ends with Ramirez bragging to his addressee (whom he has already killed), “I spend hours with your wife,” does not seem justified either by the poem’s artfulness or by any meaningful commentary on people’s capacity for violence, as “Herbert White” manages to do.

Franco would do well, in fact, to get over his intellectual crush on Frank Bidart (much as it thrills and tickles me for Bidart’s sake), because his skill and craft never begin to approach his idol’s and, as a result, any reference to Bidart invariably invites a comparison that is unflattering for Franco. “Goat Boy” quite literally picks up where Directing Herbert White, Franco’s first full-length collection published by Graywolf last year, leaves off, playing with “the backstory provided by Frank to fill out Herbert” and “the clips left over from ‘Herbert White’ [Franco’s own film adaptation],” which Franco “put[s] together, and then zoom[s] in on everything.” The result? “Everything is super close and fucked up. Weird Frames.” Not an inapt description of Franco’s poems, but what it has to contribute to Bidart’s masterpiece is unclear. (It’s worth noting two things here: that Franco’s short film “Herbert White” is quite fine and does contribute something to the original poem, and that if you’re seeking a recent book written by an actor who is as equally talented a writer, you’d be better off with Mary-Louise Parker’s graceful and heartfelt memoir-in-letters, Dear Mr. You. She conjures more music in a single line of her prose than Franco does in these poems.)

The chapbook’s first truly arresting moment comes in “Hello Woman,” which, depending on your reading of it, is either utter misogynistic and/or a poem committed to the subversion of gender norms. In it, Franco confesses: “Hello woman, I’d like to be you. / Not because I don’t enjoy my man / Body, my man strength, my man looks”—we get it, James, you’re gorgeous— “My Man mind, but because I love yours // Even more.” And yet the woman he claims to aspire to sounds more like a heterosexual porn fantasy than a real woman, with her “shapely soft parts” and “clean / Butthole in the middle.” (I suppose women are less likely to have hairy buttholes than men, which might have some bearing here, but all buttholes serve the same function.) Then, just as quickly as he tests his reader’s patience, Franco manages to surprise for the first time in the book, with the lines: “If I ever got high, it would be to be / The woman. If I did porn, I’d want to be the woman. / I don’t want to be the man in woman / I just want to be woman.”

Franco’s desire here—to be not just a woman but his Platonic conception of what it means “to be woman,” that is, a woman in porn—is an unusual expression of heterosexual masculinity, as decidedly non-normative as it is imagined out of a straight, cis view of the world. In this way, it does strike me as somehow queer, even as it operates along and according to pre-existing binaries of sexuality and gender.

This particular stance towards womanhood might also lend insight into Franco’s fascination with his friend (and unlikely pop star) Lana Del Rey, whose face appears on the book’s cover in the form of a tattoo photoshopped on Franco’s neck, and who gives the book its epigraph (“I’ve got a war in my mind,” from her song “Ride”).

She’s also the subject of two poems that appear back-to-back in a kind of diptych, “Lana Poem Essay” and “Born To Die.” The former opens rather like a Wikipedia article (“Lana has become my friend. She is a musician who is a poet and video artist”) before centering on Franco’s strong identification with her. “The only difference between Lana and me is her haunting voice,” he writes—not, notably, their respective genders. Franco concludes by invoking Del Rey’s refusal to be interviewed by him for a book: “Just write around me, it’s better if it’s not my own words. It’s almost better if you don’t get me exactly, but try.” The next poem seems to attempt exactly this, borrowing from the biography, iconography and images associated with Del Rey to enact a small drama of domestic solitude:

In my little apartment I have my pot

And my wigs, and my make up,

That I apply slowly, in slow motion,

In my Marilyn mirror with the star lightsAnd “Born to Die” on repeat…

Franco doesn’t want to fuck Lana Del Rey so much as to be her—not unlike the relationship to women he characterizes in “Hello Woman,” and not, as it happens, unlike many gay men’s relationship to Del Rey. In a sense, Del Rey is already Franco’s feminine inverse: equally concerned with the cultivation of her public persona, though hers is a play with the expectations of femininity rather than masculinity. Interestingly, when Del Rey’s music video for “Summertime Sadness” told the story of a lesbian affair despite the singer’s ostensible heterosexuality, no one accused her of gay-baiting.

In his title poem, which takes the form of an interview between Straight James (SJ) and Gay James (GJ), and is one of the most engaging in the collection, Franco does finally respond to the accusations he himself faces, settling once and for all the question of whether he’s gay in the most literal sense (not really).

SJ: OK, so, good place to start. Let’s get substantial: are you fucking gay or what?

GJ: Well, I like to think I’m gay in my art and straight in my life. Although, I’m also gay in my life up to the point of intercourse, and then you could say I’m straight. So I guess it depends on how you define gay. If it means whom you have sex with, I guess I’m straight.

Gay James goes on to make the valid, if non-revelatory point about how sex acts were not, historically, understood as the basis of sexual identity, and Straight James later admits, “Shit, I’d love to fuck you,” to his alter-ego, but the takeaway is clear: Franco is interested—sincerely—in the trappings of gay identity, and not interested in participating in gay sex. In fact, Franco might misunderstand his own interest, which seems to be located more in gender than in sexuality—specifically, how the performance of gender is shaped by audience; for a celebrity, quite literally. (“I was not the one who pulled my public persona into the gay world; that was the straight gossip press and the gay press speculating about me,” Franco reminds us in his self-interview.)

His desire for a queer identity in the absence of queer desire raises a larger question: can a queer heterosexuality exist? Can Franco’s non-normative manipulation of masculinity alone qualify him for entry?

The dilemma of the “heterosexual queer” is a quintessentially contemporary problem, a somewhat humorous reversal of the 20th century queer position: unable to change one’s sexual orientation however socially convenient or desirable that might be. (Indeed in his review of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, Daniel Mendohlson notes that it is “rather comically” that one of her characters “‘comes out’ as a straight man.”) Franco’s apparent anxiety about his own heterosexuality, also motivated by a disjuncture between sexual desire and social role, is not so dissimilar. The rapid cultural sea-change on gay rights and the sudden (if limited) recognition of trans narratives means that there has never before been so many queer models accessible in the mainstream, even as the icons of mainstream acceptance (marriage equality, Caitlyn Jenner) paradoxically erode queer difference.

I can’t imagine the difficulty of being a straight, cis person who isn’t fooled by the foundational fictions of hetero- and cisnormative power structures and doesn’t wish to perpetuate them—except to say that I can’t imagine that difficulty could possibly be greater than the various violences that many queer people still face today. This might be key to the problem that persists in Franco’s claim to queerness, and what about it that rankles so many gay men: a lack of perspective.

In my own life, populated mostly by artists, writers and academics, I know and love many people who might qualify for the designation of “heterosexual queer” by virtue of a non-normative sexual or gender expression that nevertheless fails to transcend the categories of straight and cis. But I’m not sure any of them would use the moniker for themselves, and none inhabit their privilege quite as flagrantly as Franco does in these pages.

Consider his direct response to his critics:

GJ: Okay, last question. What do you say to people who criticize you for appropriating gay culture for your work?

SJ: I say fuck off, but I say it gently.

Franco’s anger isn’t incomprehensible: he wants other people to take this “queer” part of himself as seriously as he does. And yet it demonstrates an obliviousness to why anyone for whom queerness is a central and/or compulsory identification might be bothered, and it’s this lack of self-awareness that ultimately precludes Franco from the identity he so desperately wants to get inside. Much like one’s clothes at a naked sex party, privilege must be checked for admittance.

So does James Franco have anything intelligent to say about being gay? No. Nor are his poems remarkable, even as they entertain more the average celebrity interview. But he sure as hell has something interesting to say about the fragile position of heterosexual masculinity today, and the cumulative effect of his works—from his acting and directorial choices to his nude portraits of Seth Rogen—offer a challenging take on what it means to be straight.

“There is a way to be, and then there is a way to be boring,” he quips in “New Rebel.” And while Franco might not yet have mastered the difference, he’s a straight man in 2016 whose entire project depends on the assumption that being gay would be less boring. Progress.