The Man Who Mistook Life for a Glass Wholly Full: Remembering Oliver Sacks

Author: Victoria Brownworth

August 31, 2015

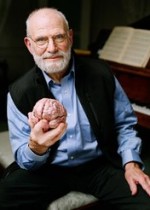

Oliver Sacks was 82 when he died August 30th at his home in Manhattan, surrounded by his partner, Billy Hayes, family members and friends. Yet it was impossible not to think the world-renowned neurologist and author of best-selling books like The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Awakenings had so many more years of brilliance to offer the world.

Sacks had been battling metastatic melanoma: An eye melanoma had metastasized to his liver. In February, Sacks had written a poignant opinion piece for the New York Times titled, “My Own Life,” in which he detailed both the shock of his diagnosis and his gratitude for the life he’d had.

Sacks wrote,

A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day. But my luck has run out–a few weeks ago I learned that I have multiple metastases in the liver. Nine years ago it was discovered that I had a rare tumor of the eye, an ocular melanoma.

He explained that the treatment for the eye tumor had left him blind in that eye, but had given him another nine years.

The liver cancer was not so generous. Not to him, nor to us.

There really wasn’t anyone else like Sacks. He was that rare being who was fascinated by everything and able to convey his abject joy in that fascination through all of his writing. The New York Times referred to him as the “poet laureate of contemporary medicine” and he was that–his work was always poetic, always had a luminous yet incisive quality to it. Whether he was writing about the brain–his specialty–or diseases or incorporating the two as he does in Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain,”which is one of his most fascinating books, Sacks was always talking to the reader in lush, vivid prose.

Sacks made the science of what he did compelling and engaging. He humanized not just his patients, but the entire concept of people with illness, who are often dismissed and diminished by the medical establishment of which Sacks was part. Humanity was abundant in his work and perhaps because of that, because of how Sacks drew one into that work and not only held our attention but made us want more, we felt we knew him–the doctor, the scientist, the man–through his writing.

Born in London in 1933, Sacks was the youngest of four siblings. His father was a doctor and his mother, Muriel Elsie Landau, was one of the first female surgeons in England and had studied with Marie Curie. Two of his older brothers were also doctors. Sacks was raised an Orthodox Jew in an Orthodox household (he writes movingly of this in Sabbath, which was published in the New York Times just a few days before his death). During the Blitz in London, he and his older brother, Michael, were sent out of the city. Sacks wrote in one of his memoirs that they were both badly abused–horribly, really, by a monster of a headmaster. It was something Sacks never fully recovered from.

Sacks came naturally to medicine, dabbling in chemistry even as a young child and earned a series of science and medical degrees in England before moving to the U.S. via Canada in 1960. In one of his memoirs, he wrote that removing himself from his family and his past associations allowed him to open up his life.

In Sabbath, Sacks wrote, “After I qualified as a doctor in 1960, I removed myself abruptly from England and what family and community I had there, and went to the New World, where I knew nobody.”

One of the reasons for going, it seems, was Sacks’ homosexuality. As a child, Sacks had deeply loved the Orthodox Jewish community of Cricklewood in London where he grew up, but after the war, it was different. A mass exodus of Jews to other places–Israel, America, Australia–decimated the community he had loved and his extended family (his mother was one of 18 children) with whom he had spent many a Shabbos afternoon eating honey cakes and gefilte fish.

Sacks was eighteen when his father flat out asked him about his sexual orientation. Sacks writes:

My father, inquiring into my sexual feelings, compelled me to admit that I liked boys. “I haven’t done anything,” I said, “it’s just a feeling–but don’t tell Ma, she won’t be able to take it.”

He did tell her, and the next morning she came down with a look of horror on her face, and shrieked at me: “You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born.” (She was no doubt thinking of the verse in Leviticus that read, “If a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: They shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.”)

The matter was never mentioned again, but her harsh words made me hate religion’s capacity for bigotry and cruelty.

Once in the U.S., Sacks completed his neurology residency in San Francisco, then went on to the Department of Neurology at UCLA. It was while living in California that Sacks experimented with hallucinogens, a topic he wrote about first for The New Yorker and then in his book Hallucinations, which was published in 2012.

He also got addicted to amphetamines, which were very much a drug of choice at the time. And he hung out with weightlifters on Muscle Beach It was there that he developed an attraction to another weightlifter, which he described in an interview for NPR’s Radiolab. It was not a reciprocal relationship and Sacks was devastated.

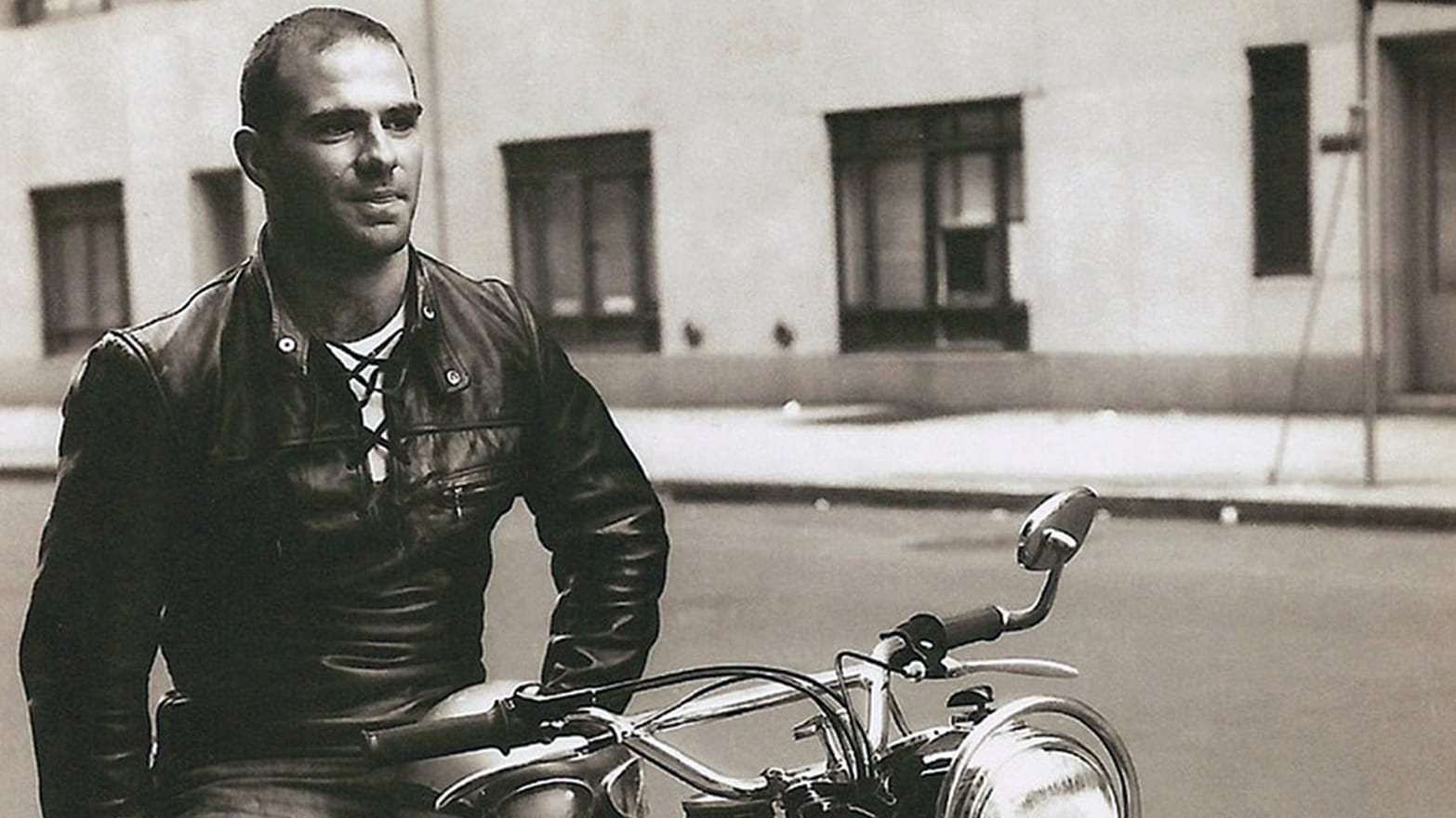

The years in which Sacks lived in California were the ones in which he experimented with everything. LSD, marijuana, amphetamines (he once took 400 over two days time and survived it). He made friends with the gay poet Thom Gunn. He rode up and down the coast sheathed in leather on his motorcycle and using his middle name, Wolf, rather than his more formally English first name. (A photo of a leathered-up Sacks on his motorcycle circa 1961 is the cover of his 2015 memoir, On the Move.)

But as enticing and expansive as those years in California may have been, as Sacks wrote in his most recent essays, he was searching for something more in his life. “I craved some deeper connection–“meaning”–in my life, and it was the absence of this, I think, that drew me into near-suicidal addiction to amphetamines in the 1960s.”

Sacks moved to New York City in 1965 and recovered from that addiction while working in the Bronx hospital he writes about so vividly in his first best-selling memoir, Awakenings.

Sacks moved to New York City in 1965 and recovered from that addiction while working in the Bronx hospital he writes about so vividly in his first best-selling memoir, Awakenings.

This is the book that made Sacks famous. It is also the book that revealed him for who he was above all else: a man who loved people deeply and cared for his patients on a level that was truly uncommon at that period of time in medicine. Sacks writes of his patients, “Their ‘conditions’ were fundamental to their lives and often a source of originality and creativity.”

He saw them not just as people with diseases of the brain to be cured or studied, but as people who were finding ways to cope with bodies that had been altered or broken or damaged, often irreversibly. Sacks always maintained a sense of awe at what his patients were able to overcome, or to live with. One imagines it helped him in his own final illness.

Sacks opens his memoir On the Move with the story of being sent out of London at eight on with his older brother, Michael, who was sixteen. (Michael never recovered from the horror of their experience and lived with Sacks’ father until his death.) Sacks writes that “I had a sense of imprisonment and powerlessness” and that “I longed for movement and power.”

It is this that he gives his patients in Awakenings. He frees them from their imprisonment and gives them back a sense of power over their own lives–these men and women who have been warehoused in the Bronx for decades until Sacks, fleeing his own demons, discovers them and opens up their world.

His work revealed patients to the world and sometimes even to themselves, as he did with the patients in the Bronx hospital in Awakenings. The book was so powerful, Sacks’ friend, the poet W.H. Auden, called it a work of genius and “a masterpiece.” The praise, Sacks said, made him weep.

Awakenings resonated for a long time. Not only was it a best-seller, but the 1973 book was made into a film directed by Penny Marshall in 1990. Robin Williams played Sacks, Robert DeNiro, one of his patients.

The film was nominated for three Oscars: Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay (Stephen Zaillian) and Best Actor (DeNiro). Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film a four-out-of-four star rating, writing,

After seeing Awakenings, I read it, to know more about what happened in that Bronx hospital. What both the movie and the book convey is the immense courage of the patients and the profound experience of their doctors, as in a small way they re-experienced what it means to be born, to open your eyes and discover to your astonishment that “you” are alive.

Sacks himself said after seeing the film of his work,

I think in an uncanny way, De Niro did somehow feel his way into being Parkinsonian. So much so that sometimes when we were having dinner afterwards I would see his foot curl or he would be leaning to one side, as if he couldn’t seem to get out of it. I think it was uncanny the way things were incorporated. At other levels I think things were sort of sentimentalized and simplified somewhat.

Sacks was not one to sentimentalize. Even when he is writing about his childhood in Uncle Tungsten or his patients in Awakenings, he is never sentimental. But nor is he distant or cold. He is, at all times, curious.

It is Sacks’ curiosity that compels him and compels us, his readers–millions of us, it seems, as there are millions of his books in print. What is it that we are so drawn to in Sacks and his writing?

As someone who began in medicine and then switched to journalism and covered hundreds of stories about AIDS, cancer and other diseases as a medical reporter in the 1990s, what has always drawn me to Sacks the writer is the feeling that we were seeking the same thing: He was searching as a doctor and humanitarian for an answer and I, the reader, was searching along with him. That ability Sacks had to connect us, his audience, with both his patients and himself and the science of his inquiry was the core of his brilliance. When he moved to New York to make what he calls a “deeper connection,” it’s definitely that which he achieved. We can actually feel that connectedness in his work. The effort to connect, the determination to find some link that will allow his patients to be connected, too.

In his essay on dying, Sacks draws comparisons between himself and the 18th century philosopher David Hume who wrote a short autobiography of himself in a single day in 1776, when, at 65, Hume discovered he was dying.

Sacks has written thirteen books, all of them memoirs of one sort or another. In that essay, the title borrowed from Hume, Sacks writes, “While I have enjoyed loving relationships and friendships and have no real enmities, I cannot say (nor would anyone who knows me say) that I am a man of mild dispositions. On the contrary, I am a man of vehement disposition, with violent enthusiasms, and extreme immoderation in all my passions.”

How can one not love a man–especially a writer–who is given to “violent enthusiasms”? Is this not the very thing that entrances readers about Sacks? That he has always thrown himself fully into every aspect of his life and in so doing, brought us with him?

In the disquisition he did with Radiolab, which I heard just a weekend ago and which thoroughly mesmerized me the way all Sacks’ talks have done, he spoke about how intrigued he had always been with indigo. The color. Indigo is one of the seven colors on the visible spectrum and lies between blue and violet. The color indigo was named after the indigo dye derived from the plant. The first known recorded use of indigo as a color name in English was in 1289.

Sacks was captivated and, as he notes, being a man of “extreme immoderation in all my passions,” he took a “cocktail of cannabis, amphetamine and LSD” and “successfully set out to envision a splash of true indigo,” the color he had been fascinated by since childhood. According to Sacks, he achieved his goal and could “taste” the color vividly.

One of the many unique aspects of Sacks was his own disability. Sacks had prosopagnosia or “face blindness”–the inability to see and remember faces. He wrote about this for The New Yorker in 2010 where he discusses how he didn’t even know he had the disorder until middle age. In The New Yorker, Sacks describes the disorder but also, humorist that he is, tells some stories of being lost and of not recognizing people he had known for years, including his own assistant. And he noted this,

Several times I have started apologizing to large, clumsy, bearded people and realize that it’s a mirror. But it’s even gone a stage further than that. Fairly recently, I was in a café in Chelsea Market with tables outside and while I was waiting for my food I was doing what people with beards often do: I started to preen myself and then I realized that my reflection was not doing the same thing. And that inside there was a man with a beard, possibly you, who wondered why I was sort of making faces at him.

(Sacks also talks about his face blindness here).

In his most recent memoir, On the Move, which was published in April 2015, Sacks talks about being gay for the first time in depth. After leaving England, Sacks explored his gayness with some abandon, though it was before the “summer of love.” The strictures of his Orthodox upbringing and the trauma from his abuse at boarding school impinged on him in different ways. He enjoyed men in Amsterdam and America. Yet he describes how he had a “joyous” affair with a much younger man on his 40th birthday and then doesn’t have sex again until his 70s when he and Billy Hayes fall rather madly in love.

It’s the stuff of novels. Or memoirs.

In the June 2015 Vanity Fair, writer Lawrence Weschler, former staff writer at The New Yorker and a longtime friend and would-be biographer of Sacks wrote a sort-of bio/tribute/revelatory essay on Sacks in which he writes what many of us who have followed Sacks avidly through the years have learned: Like many of his generation, Sacks was conflicted about his homosexuality for years. Most of his life, really. Weschsler writes that this was the aspect of Sacks he wanted to detail and it was then that Sacks decided they were better as friends than as biographer and subject.

This was more than 30 years ago.

There are excerpts from the notebooks in the Vanity Fair piece that are moving and compelling and offered with Sacks’ blessing.

Weschler writes, “Early on, Oliver had agreed to let me write his biography, and I began filling what would become fourteen notebooks of accounts of our meetings and conversations. Much of our time consisted of his telling me ever more (to his mind) scandalous tales in the hopes that I, too, might finally concur in his estimation that his homosexuality was a terrible blight, a disfiguring canker on his character, which I just as regularly refused to do. He would not be assuaged. Midway through the process, he began to have second thoughts about our whole biographical project. Was there any way that I could tell his story without the homosexual stuff? Alas, there wasn’t.”

Weschler adds that he “stored the notebooks in the back reaches of one of my closets. And we remained close. Oliver was present at the party celebrating my own marriage and would become a doting godfather to our daughter. Over the years, we and the few other friends who knew of the issue would try to pith him of his self-contempt and self-denial regarding his sexual nature–for the longest time, to no avail.”

And then came Billy Hayes. Hayes, author of The Anatomist, fell in love with Sacks and Sacks with him.

In On the Move, Sacks writes of “dipping into” Kraft-Ebbing and Havelock Ellis, the sexual pathologists of the time whose focus on homosexuality drove many a pre-Stonewall lesbian or gay man even deeper into the recesses of the closet. Yet while he read these men avidly, he writes that at twelve “I felt it difficult to feel that I had a ‘condition,’ that my identity could be reduced to a name or a diagnosis.”

Not surprisingly, Sacks details the impact his religious upbringing and perhaps even more so, his mother’s religious beliefs–having been raised in the 1890s–had on his views of his own sexuality. He also notes that “in England in the 1950s homosexual behavior was treated not only as a perversion but as a criminal offense.”

It would be years after Sacks fled his London home that homosexuality would cease to be a crime.

On the Move is the most personal of Sacks’ writing and the most detailed about his feelings about his sexuality, from adolescence to adulthood.

In one of his exchanges with Weschler, in June 1982, Sacks talks about a letter he had gotten from Thom Gunn. It had, he tells Weschler, obsessed him. He wrote over 200 pages of replies, none of which he sent. Gunn had been attracted to Sacks’ intellectual genius, but had found him lacking in empathy–the very thing Sacks has become known for throughout his professional life. Gunn wanted to know what had changed. How had Sacks re-made himself into the man he had become, the man so deeply empathic?

Sacks tells Weschler about Gunn, “What had excited me in Thom Gunn’s poetry was its homoerotic lyricism, a romantic perverseness. The perverse turned into art. He gave a voice to things which I’d imagined singular and solitary, and this filled me with admiration.

“And the other side of this: he dealt with elements in myself with which I had never come to terms. And still haven’t.”

In July 1982, Sacks tells Weschler, “My analyst tells me he’s never encountered anyone less affected by gay liberation. I remain locked in my cell despite the dancing at the prison gates.”

The last years of his life were spent dancing with Billy Hayes. Some photos accompany Weschler’s piece in Vanity Fair and in one Sacks stands in some body of water, a swimming cap on his head, salmon swim briefs on. His body is not the body of an old man. He’s muscular and trim, with a swimmer’s build. In subsequent photos taken by Hayes, who is also a photographer, Sacks is contemplative, but still exudes an intensity, a liveliness. This is not a man anticipating death. This is a man deeply involved with life.

In Sabbath, Sacks details his return to Israel, Hayes with him. It is a coda of sorts. Hayes is welcomed as Sacks’ partner.

Sacks writes, “I felt embraced by my family in a way I had not known since childhood. I had felt a little fearful visiting my Orthodox family with my lover, Billy–my mother’s words still echoed in my mind–but Billy, too, was warmly received. How profoundly attitudes had changed, even among the Orthodox, was made clear by [Sacks’s cousin] when he invited Billy and me to join him and his family at their opening Sabbath meal.”

What if things had been different, Sacks asks? Then writes,

In December 2014, I completed my memoir, On the Move, and gave the manuscript to my publisher, not dreaming that days later I would learn I had metastatic cancer, coming from the melanoma I had in my eye nine years earlier. I am glad I was able to complete my memoir without knowing this, and that I had been able, for the first time in my life, to make a full and frank declaration of my sexuality, facing the world openly, with no more guilty secrets locked up inside me.

That declaration must have been freeing. But what a loss that it took decades to be revealed by a man so captivated by the workings of the human brain and psyche. One cannot help but lament Sacks being so constricted by his sexuality when the rest of his life was so broadly expansive.

In his essay My Own Life, Sacks wrote, “I have been increasingly conscious, for the last 10 years or so, of deaths among my contemporaries. My generation is on the way out, and each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself. There will be no one like us when we are gone, but then there is no one like anyone else, ever. When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate–the genetic and neural fate–of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.”

Sacks’ Facebook page stated Sunday that, “Oliver Sacks died early this morning at his home in Greenwich Village, surrounded by his close friends and family. He was 82. He spent his final days doing what he loved–playing the piano, writing to friends, swimming, enjoying smoked salmon, and completing several articles. His final thoughts were of gratitude for a life well lived and the privilege of working with his patients at various hospitals and residences including the Little Sisters of the Poor in the Bronx and in Queens, New York.”

The post goes on to say that a foundation to study the brain has been established in Sacks’ name and that there is a great deal of writing left that one imagines his partner, Hayes, or family, will see published at some point. Certainly there are many of us eager to have every scrap of his work that is extant.

I shall miss Oliver Sacks. Miss coming upon his work in The New Yorker or the New York Times. Miss hearing his voice in interviews,that Oxonian accent still so strong despite his 55 years here in America. Sacks leaves such a legacy–his writing, his love of language, his incisive investigations into the nature and workings of our brains. He leaves us with those “violent enthusiasms” and with his sense that there was always another page to turn, another layer to be peeled back, another something just beyond reach that should be striven for. He was a brilliant man, Oliver Sacks. But most importantly for us, his readers, he was a curious man. And that curiosity, that fascination with all things, drove him and drove us to him. We were so fortunate to have him while we did.