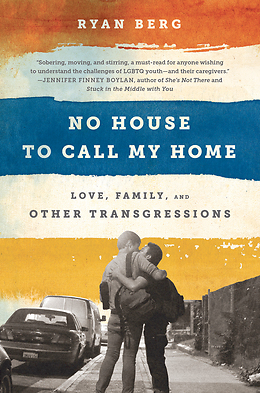

A Look at LGBTQ Homeless Teens: Read an Excerpt from Ryan Berg’s ‘No House To Call My Home’

Author: William Johnson

August 17, 2015

This month, Nation Books is releasing No House To Call My Home: Love, Family, and Other Transgressions, a memoir by writer and activist Ryan Berg. The book is an illuminating account of the lives of a group of New York City LGBTQ homeless youth.

From publisher:

In this lyrical debut, Ryan Berg immerses readers in the gritty, dangerous, and shockingly underreported world of homeless LGBTQ teens in New York. As a caseworker in a group home for disowned LGBTQ teenagers, Berg witnessed the struggles, fears, and ambitions of these disconnected youth as they resisted the pull of the street, tottering between destruction and survival.

Focusing on the lives and loves of eight unforgettable youth, No House to Call My Home traces their efforts to break away from dangerous sex work and cycles of drug and alcohol abuse, and, in the process, to heal from years of trauma. From Bella’s fervent desire for stability to Christina’s irrepressible dreams of stardom to Benny’s continuing efforts to find someone to love him, Berg uncovers the real lives behind the harrowing statistics: over 4,000 youth are homeless in New York City—43 percent of them identify as LGBTQ.

***********

The house is mostly silent. Nearly all of the residents are away at school. The only thing I can hear from where I’m sitting in the office is a heavy, low voice. It’s coming from the dinner table down the hall. “Not again,” I think as I look at the clock: 2:00 p.m. I grab the key ring and get up from the desk.

The venetian blinds are drawn. Thin wedges of sunlight slice through the slats and marble the tabletop. Benny is balancing on the rear legs of his chair. His head is tilted and the telephone is caught between his ear and his shoulder. As he talks he wraps the coiling cord around his finger. A manicured but full beard traces the outline of his jaw and makes him look older than his nineteen years despite his short and stout frame. Benny doesn’t look up as I motion for him to hand over the phone.

“Yo, I’m definitely feeling that,” he says into the receiver. “For sure.”

I can always tell when he’s on the chat line because his voice drops two octaves lower than normal. His obsession with talking to strangers on the phone is a growing concern for the staff. He pays for the chat lines with one of the many credit cards he’s received, despite not having a job—a detail he’s managed to keep secret from everyone until recently. When he maxes out one card, he moves on to the next. This allows him to talk endlessly to anonymous men on the other end of the line, disclosing the most intimate details of his life, letting down the guard he tries to maintain in the group home. The staff has talked with him about the level of disclosure in his conversations, appropriate boundaries, and money management, but he won’t have it. He’s “all grown,” he says. We need to stay out of his business.

“Can I have the phone, please?” I whisper. Benny looks up, doesn’t cover the mouthpiece.

“Leave me the fuck alone, son. Can’t you see I’m busy?” He winks at me, as if we’re both in on a joke, then turns away and presses his lips into the receiver. “Nah, that just my roommate. He always be fiending for the phone.”

Sometimes Benny tells the men that he has his own apartment. Other times he says he still lives at home. But he never mentions foster care or the group home.

When I catch his eye again I smile weakly at him, point to the clock on the wall. He rolls his eyes and looks away.

“Benny.”

He ignores me.

“Benny, you can’t be on the phone now, I’m sorry.”

“Wait,” he hisses at me from the corner of his mouth, shooing me away with his hand. “No, not you man,” he says into the receiver. “No really, we good. Oh, word? All right, hit me up later, son. No, we cool. Sure, later.”

Benny slams the phone down into its cradle and glares up at me. “You really know how to get up in my shit.”

“I’m sorry, but phone privileges start at 4:00 p.m.”

I disconnect the cheap RadioShack model from the wall and twine the cord around. “Ms. Celeste said you’re supposed to ask permission before taking this from the office.”

“Actually, phone privileges start at 4:00 p.m. for students. I’m not a student, so I can use it whenever I want.”

In my short time at the 401, I’ve already learned Benny has a habit of correcting residential counselors and caseworkers on the program’s arcane rules and regulations. After living in the system for so long he knows his rights better than most legal advocates. He finds the loopholes and he tends to fabricate others. I’ve been studying the House Rules and Regulations packet to prepare for a situation just like this. But the circumstances surrounding Benny are trickier. A few months back, before I started working here, his mother died. Complications from AIDS. Now everyone is unsure how to move forward with him, afraid that pushing him too hard may derail all the gains he’s made. I haven’t been trained to deal with this kind of loss, so I decide to tread lightly and stick to the packet as a foundation for our conversation. My breathing escalates.

“You’re right, students get to use the telephone after 4:00 p.m. But cutting class doesn’t mean you’re no longer enrolled. It means you’re truant. You can use the phone after 4:00 p.m. like the other students.”

His face reddens. He stands up and shows me his back. I get a “whatever” and a flip of the hand. He moves into the living room, collapses on the couch, and turnson the TV. House rule: no television during daytime hours.

Benny tucks a pillow between his knees, flips to the soap opera Passions. On the screen a woman is staring into her crystal ball predicting the future to a man with a chiseled, sharp jaw line and a California tan. Her premonition, bleak.

In moments like this, I’ve seen Ms. Celeste—the worker the residents call Mama—simply walk up and unplug the TV and take the remote into the office with her. I opt for a less combative approach.

“Let’s put together a résumé for you,” I suggest.

Benny’s eyes don’t move from the screen. The last job he had was at Met Foods down the block. He lasted two weeks until he got fed up with the manager telling him what to do and pushed past him, knocking over a display case of tomato sauce. When the staff asked why he was fired, Benny said, “Some people just don’t know how to hear the truth.”

“If you’re not going to school we should at least prepare you to look for work,” I tell him now. Benny grabs the pillow from between his legs and chucks it across the room.

“I can’t hear the TV,” he says, his face again filling with color.

I’m unsure what to do, so I smile at him. “I’m sorry, but you know the rules. Turn it off, please.”

Benny lifts the remote control, points it in my direction, and presses the power button.

“Off,” he says.

When Gena, the 401’s house manager, hired me in May 2004, she said there was quick learning curve. No time to leisurely figure things out. “Walk in with confidence, she said. “The residents can sniff out fear. If you don’t adapt quickly they’ll go for the jugular. Whatever you’re self-conscious about,” she said, gesturing to my bald head to serve as example, “they’ll find it and they’ll use it.”

It wasn’t until Ms. Celeste had me go to Benny’s room on one of my first days on the job to wake him up for school that I realized where my insecurity lied. Benny didn’t lift his head from his pillow as he muttered, “Go away, tourist.” His words shot me outside of myself. I saw this bald, white guy in a dilapidated house in Queens surrounded by kids of color and wondered, “What am I doing here?”

A man from the Midwest with no social service experience, I had no right to step foot inside the 401. And who was I to tell anyone how to succeed in life? I knew from my few weeks of training that a disproportionate number of children in the New York City foster care system are people of color. Although most of the management team in the LGBTQ program, like Gena, were white, all entry level residential counselors were black or Latino, mostly women. It was obvious a dynamic had shifted when I was hired as a residential counselor. Gena was trying something new: hire someone who seems to care regardless of race, class, or gender. It was an experiment with a high probability of failure. I would have to rely on intuition when feeling out what social workers call “cultural competency.” The only guidance I was given in that regard was when I was told not to impose my white, middle-class expectations on the youth. I understood what that meant in theory, but I couldn’t envision how that would look in practice. I had to learn on the go.

Gena explained her reasoning for hiring me when she told me I had the job. “These children are in crisis,” she said. “Most of them have never been given a chance and have never had any guidance or appropriate attention from adults. Their relationships with family are in ruins, their whole lives they’re disposable, worthless because of their sexuality or gender identity. Some of the residential counselors here do care, some don’t. I’d prefer to have a white guy from Iowa who gives a shit than someone else who doesn’t.” She paused and looked at me intently. “The youth will push you and push you in order to test you, expecting you to leave like everyone else has. But really they want you to say, ‘Keep acting up all you want. I’m not going anywhere. I won’t abandon you.’”

I entered the 401 that first day expecting to be introduced to the residents. Instead I walked into a maelstrom of shrieks. All I could make out was that the thick Latino kid screaming and flailing around the room wanted to watch a different TV program from what was on. Instantly I wanted to deaden the noise with a drink. Ms. Celeste seemed unfazed. She walked me through a recital of inter-house feuds, personality quirks, things permissible and things not, as I tried to keep a mental stockpile of everything.

“Don’t let the key ring out of your sight. Don’t leave the snack closet unlocked or it’ll be ransacked. The residents will try to convince you to give them money from petty cash: don’t. Don’t hand out extra laundry detergent until the first of the month. Sybella can’t eat cheese, Montana can’t smoke on the stoop, Rodrigo can’t be given a home pass no matter how much he persists.”

A thin girl in skintight purple jeans and dangly earrings ran up to Ms. Celeste and hugged her tightly, then ran off without so much as a word.

“Touching or any kind of physical contact is discouraged because it can be misinterpreted,” she said. “But how are you going to deny a hug from a child?”

Ms. Celeste looked around the room, as if to make sure she hadn’t overlooked anything.

“Oh, and Benny,” she said, her eyes narrowing, “the one acting the fool about his TV program. Well, Benny’s convinced he’s all grown now, practically wrote these rules himself, so he thinks he doesn’t need to listen to nobody. Don’t give in to him.”

My shift would be Wednesday morning through Friday night. I’d be the residents’ primary caretaker during the day and the sole caretaker during the night. For the entirety of my shift I wouldn’t be allowed to leave the premises. The drink I was craving when I stepped through the front door would have to wait.