Harvey Milk & the Politics of Neighborhood Life

Author: Ben Shepard

November 17, 2010

Friends Remember Mayor of Castro St

From 1992-1995, I lived in San Francisco. I stumbled into a job working 12-8 AM shifts at a housing program for people living with HIV/AIDS. I spent most of those late night shifts listening to the residents at the facility tell stories. My greatest surprise was how meaningful people found it to recall the days of Harvey Milk. I eventually took to the streets to compile oral narratives from people around the city.

Throughout the interviews, those involved recalled those days as perhaps the most meaningful and cogent periods of their entire lives. Perhaps this speaks to the enduring appeal of the narrative of Harvey Milk’s ascent and tragic ending.

Cleve Jones:

Former Harvey Milk aid. I went to high school in Phoenix. Actually, the first time I came here, I was traveling here with a group of Quakers. I had come to the Bay Area to attend the annual gathering of Quakers from the West Coast held out at Mirage. I was 17 and that was when I had come out of the closet. There was a gay Quaker couple at that meeting and they were active with the Society for Individual Rights. So, when I was 17, I met a number of the real pioneers in the movement and then I went back to Phoenix and joined the gay liberation group there. It was a very repressive dangerous situation and I was very anxious to move to San Francisco.

I don’t remember the day I met Harvey, I just know I met him on the street on the corner of 18th and Castro. He flirted with me and I told him he wasn’t my type. When he started running for office, I wasn’t really into electoral politics. I was quite the little radical boy. I lived in a communal house in the Haight/Ashbury, worked as little as possible and went to all the clubs.

Robin Tichane:

I was in New York in 1970, and it was a joke. Gay politics in NYC at the time of Stonewall was nothing, zero. I came out here and there were gay politicians. Harvey Milk was trying to run for supervisor. [Richard] Hongisto would go to gay drag balls. He would have his photo taken with a drag queen on either arm and it would make the paper.

Peter Groubert:

The political climate in the neighborhood changed a whole lot. Harvey and Scott moved into the neighborhood, I guess it was ’73ish, and opened the Camera Shop on Castro up near 19th. There’s a Skin Zone or a Body Shop there now. We, the gay community, started to get involved with politics in the city. We wanted a say in what was going on. We were still being harassed by the police.

Hank Wilson:

I moved from Sacramento to here. I didn’t know there were gay bars in Sacramento. I discovered Polk Street, in the city, by chance and I started commuting for my sex life. After a while, I was commuting so much, I thought I’d better move. It’s one thing to go on weekends, it’s another to go in the middle of the week.

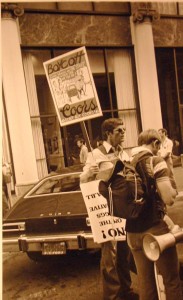

Photograph by Howard Petrick shows Howard Wallace (in sunglasses). Courtesy of San Francisco Public Library

In the mid-’70s, homophobes would attack us right at 18th and Castro! Not on the outlying streets! The perception of us as a myth was that we were weak, gentle poets with limp wrists, who would run. Anyway, I ran into Howard Wallace. He was handing out a leaflet about police problems on Castro Street and I went to a meeting. That was the formation of BAGL, Bay Area Gay Liberation, in ’74. And we turned that around. That’s one of the important things I’ve done with my life.

I met Tom Amiano* in BAGL. When we started to go political, our core group was about 30 gay teachers, most of them freaked out because they weren’t ready to go public. But Tom and I, being the arrogant/gifted teachers we were, we had the support of our faculties. They knew we were good teachers. So we pushed the issue.

A lot of our traditional leaders told us that we were pushing the wrong issue and we were going to set back the gay movement because we were dealing with an issue of children. And it was ahead of our time. Harvey Milk was one of the few leaders who came to the school board. Other noted leaders like Jim Foster, they didn’t come. The established leaders in the community deserted us and we won. Overnight a new generation of leaders was born.

Interviewees, several of whom had volunteered for his election and the cause he stood for, recalled the unlikely ascendance of Harvey Milk into the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977. “You gotta give ’em hope,” Milk stumped. California State Senator Briggs launched a state wide proposition called “The Briggs Initiative” to keep homosexuals out of teaching positions in California schools. The nation witnessed its first openly-gay national official in action (Shilts, 1982). Interviewees recall the campaign led by Milk against a first glimpse of the Christian Fundamentalist Movement. The community galvanized in action around a man who would become the first of many martyrs.

Peter Groubert:

There were two communities: the committed political community and the weekend warriors. The weekend warriors were people who were young, gay, some professional, making some fairly good money. They liked to dress well, eat well, party hard and they voted for what the clubs said was the best. Few people read any of the literature or followed up. The political people, like Harvey, Dennis Perone and Rick Stokes, were out in the street.

The people from the older, established organizations such as SIR, Society for Individual Rights, the Mattachine Society become the backbone, the money people.

Photo: GLBT Historical Society

Robin Tichane:

Harvey Milk was just kind of an odd personality and he specifically hated the Gay Men’s Business Group. I remember going in to visit him once and asking him to join. He was kind of huffy and “oh, who put you up to this?” He didn’t get that we’re all kind of doing this ourselves.

I don’t have any ax to grind, but he was a crank. He wasn’t into how he appeared. He was a sloppy dresser. He was a brilliant talker. He did have language down and really inspired you.

Hank Wilson:

We got behind Harvey’s campaign. We registered easily 10,000 people. We worked the street corners. We did it in a way that was out of the closet. It was inspiring to a new generation of people who had migrated to this city for a better life. And then we had an opportunity. Harvey was a vehicle and we got him elected.

Cleve Jones:

Politically, everything was new. So I met Harvey during that time and was charmed by him. I was a film major; he told me I had no talent but that I should be an organizer. I changed majors to Urban Studies, got an internship at his office and did that until he was killed.

Hank Wilson:

Anyway, we came back here. Briggs was beating the drum. He was also in Miami. They put the thing on the ballot. I took six months off of work to campaign full time as an out teacher. We did the radio shows, every talk show we were invited to. The early polls showed that we were going to lose two to one.

We didn’t turn it around by ads or by raising money. We turned it around by having thousands of gays and lesbians get their bodies out on street corners. I think that it was an incredible opportunity when Anita Bryant attacked us. The whole Orange Tuesday “Save Our Children” Campaign was opportunity for us. For the first time, the word was out.

Cleve Jones:

It wasn’t easy. You had a huge population of people coming to the urban centers to come out And you had the emergence and the creation of this community organization that had not been tested.

The first real test was the Briggs Initiative and we were energized by the Anita Bryant Campaign. I was out here on the street blocking traffic on Orange Tuesday. I picked up on the Briggs Initiative a year before it qualified for the ballot. I had a conference at San Francisco State where we brought in gay students from 20-something campuses and we started organizing.

Harvey saw it as an incredible opportunity. We never thought we’d win, but we would use it as an opportunity to get people to come out. It was an incredible rallying point. It was the first real outpouring of activism and we thought we would lose. It was so astonishing when we won. I think people were very much aware that we’d crossed this threshold, that we had created a state-wide structure, that we had raised significant money, we had mobilized considerable numbers of troops.

Hank Wilson:

Cleve and all his marches, the community, if they did something against us, we got in their face, we marched. The call would go out to the community. The signs would go up and hundreds and thousands of people would turn out. And we turned out because we cruised at those events and we still do. That’s something that we have that’s special. We would have a good time. We would be political. We would chant. We would be together and we would put up a fight. We would challenge every attack against us. It was very, very exciting.

——

Many helped beat the Briggs initiative after Harvey Milk was elected, only to watch him get shot within a year of his election. The interviewees recall those heady days preceding the White Night Riots in reactions to the short sentences of Milk and Moscone’s assassin, former policeman and supervisor, Dan White. Activists burnt police cars and the police raided on the Elephant Walk. “The riots stood as a declaration,” Cleve Jones observed. “We all live in San Francisco,” placards read a continent away on Christopher Street in New York City the nights after the riot.

Only a year later, people in the Castro began dying of a strange cancer.

——

Excerpts from White Nights and Ascending Shadows: An Oral History of the San Francisco AIDS Epidemic, The Before Years through AIDS Inc. Cassell Press, 1997

* Tom Amiano was elected onto the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1994.