Justin Hall: Queering Comic Books

Author: William Johnson

August 31, 2011

“One of the most important aspects of comic books as a medium is how it manipulates time. In a very profound sense, the language of comics is an allegorical description of time and movement in a static form. This allows for a complexity that no other medium can touch.”

Justin Hall is a cartoonist and writer, like Alison Bechdel and Howard Cruse before him, who is reshaping the comic book medium to reflect his own queer vision.Based in San Francisco, Hall has been producing independent comics since 2001. His work includes True Travel Tales, Hard To Swallow and A Sacred Text. His comics have also been showcased in publications such as the San Francisco Bay Guardian, The Book of Boy Trouble, The Best Erotic Comics series, and The Houghton Mifflin Best American Comics 2006.

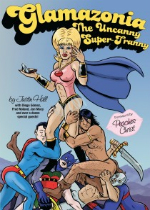

Hall’s recent graphic novel, Glamazonia: The Uncanny Super Tranny (Northwest Press), was nominated for a 2011 Lambda Literary award. He has been active as the Talent Relations Chair of Prism Comics, a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting LGBT comics and their creators and readers. He also teaches a class in Queer Comics at the California College of the Arts.

Lambda sat down with Hall to discuss his love of comic books, the straight and queer cartoonist communities, and his thoughts on broadening LGBT content for larger audiences.

Johnson: When did you first become interested in comic books?

Hall: I learned to read with them, and I stayed in love with the medium my entire life. The combination of words and pictures has always worked especially well for me.

Johnson: Was there one comic in particular that really showed you the power of the medium?

Justin Hall: I grew up reading the Franco-Belgian comics Tintin and Asterix, as well as the American superhero comics. That balance was a good introduction to a variety of styles and possibilities in the medium. Jack Kirby, the creator of The Fantastic Four, Thor, and the Hulk, was always a big hero. His imagination was so vast, and his visual style so dynamic…

Johnson: …and that dovetailed into your own desire to start creating comics?

Hall: Yeah, I’ve been passionate about the medium my entire life, and have always known I wanted to make them for as long as I can remember. I used to use up reams and reams of my mom’s typing paper compulsively drawing my own comics as a kid. Sometimes I’d even start drawing on the pencil sharpener or the top of my desk if I ran out of paper.

Johnson: Do you think your queerness was tied to your comic fandom?

Hall: Well, superheroes have an undeniable homoerotic edge to them—muscular men in tights flying around and all that. It wasn’t until later in my life, though, that overt queerness was even possible in comics… I take that back—the queer underground in comics started around the time I was born, actually, but as a child I didn’t have access to underground material. It’s only very recently that there are actually all-ages queer comics, such as The Princess by Christine Smith, about a young trans-girl. But I’d say the first queer representations in comics I ran across were the dyke punks of Love and Rockets—and I loved them!

Johnson: So how did your comic book career begin?

Hall: I saw the Dead Sea Scrolls in their museum outside of Jerusalem and did a comic book about it [A Sacred Text]; it received a Xeric Award Grant, which enabled me to self-publish the book. This was when I was in my late twenties and traveling around the world with a backpack.

My first series of comics following A Sacred Text was called True Travel Tales, and was a collection of autobiographical and biographical travel stories. I did that for a few years. After True Travel Tales, I teamed up with Dave Davenport to do a gay porn comic called Hard To Swallow, which ran for four issues. I was also working off and on with my character Glamazonia, the Uncanny Super Tranny…I finally produced a big, full-color book of her adventures last year.

Clearly, I have a lot of different interests, and so it’s difficult for me to stay still on one project for too long. Now, I’m editing and compiling an anthology for Fantagraphics called No Straight Lines: Four Decades of Queer Comics, which will contain a comprehensive “best of” collection of LGBT cartooning along with an essay on the history and cultural context of the material, due out in February 2012. This book project has also spun out into an ongoing class that I’m teaching on queer comics at CCA [California College of the Arts].

Johnson: As a storyteller, what inspires you about the comic book medium?

Hall: One of the most important aspects of comic books as a medium is how it manipulates time. In a very profound sense, the language of comics is an allegorical description of time and movement in a static form. This allows for a complexity that no other medium can touch. So, in the space of one comic book page, a creator can reference and create narratives on multiple intersecting time frames. This obviously is highly useful for memoirs. Howard Cruse, for example, uses this technique very well in Stuck Rubber Baby, which is a kind of faux-memoir.

Autobiographical material has been a constant thread in my own work as well, and memoir is a genre for which the comics medium is especially well-suited for a number of reasons.

One example is that there’s a visceral immediacy to having images paired with the words that can work to the creator’s advantage. This can be used to create an intimacy between the reader and the subject— witness Phoebe Gloeckner’s Diary of a Teen-Age Girl, or to create a broader impact—some of my splash pages in True Travel Tales, for example.

Finally, one can move between internal and external realities in comics in really sophisticated ways that work well for memoir. Moving into an interior fantasy or flashback in a movie or a book, for example, can be clunky, but is often much easier to pull off and more interesting aesthetically in comics.

One other thought: when I was doing autobiographical sex stories in Hard To Swallow, comics seemed like the perfect medium to use. You can determine exactly the tone and visual style in creating a sex scene in comics in a way that’s harder to do in prose or film, especially without sliding into cliché.

Johnson: I want to ask you about your initial autobiographical books. They are very different in tone and style than a Jack Kirby comic. Did you have a different set of inspirations at this point in your life?

Hall: Yeah, by that point I was reading the independent and alternative comics that were around at the time, such as Love and Rockets, Slutburger, Baker Street, and others…I was aware of the autobiographical genre in comics. I wanted to do something different from a lot of that genre, though.

Most autobiographical comics are from the Harvey Pekar school, by which I mean they tend to be about the mundane aspects of life and how lame the protagonist is–the “woe is me” school. I was interested in living a crazy, unusual life, though, and making comics about it, so I was more drawn to folks like Mary Fleener, whose comics were filled with sex, drugs, and rock and roll.

In my experience, the craziest stories happened on the road, so I figured if I could collect those tales, I would have narrative gold. I also wanted to avoid a common trap of travel narratives; often, travel stories are simply “look at this cool, exotic place I’ve been to.” Which of course is not a story. I wanted to make sure that my travel tales were first and foremost gripping narratives that didn’t rely on the exoticism of the local to carry the story.

I was also traveling with my paper and ink in my backpack for a good part of this time period. I would settle somewhere and actually be able to draw my comics at least in part from life. For example in True Travel Tales #2, the images of the thatched, balsa-wood huts floating on the river were drawn from the view out of my hotel window in Iquitos, a city in the Peruvian Amazon. And the Spanish Bible verses glued to the pages of the grandmother quoting scripture I actually cut and pasted from the Spanish language Gideon’s that was in the hotel room. And yes, I realize that I am, indeed, going to hell for that.

The third of the True Travel Tales comics, called “La Rubia Loca,” was included in the 2006 Houghton Mifflin Best American Comics.

Johnson: Who was the editor of that edition?

Justin Hall: Anne Elizabeth Moore was the series editor and Harvey Pekar was the book editor.

Johnson: Awww Harvey…

Hall: He was a strange dude, but all of us indie comics types owe him a lot.

Johnson: Do you find a divide between straight editors and publishers— even on the independent side—and gay creators?

Hall: Traditionally, queer comics have existed in a parallel universe to the rest of the comics industry. For the most part, they weren’t sold in comic book stores, published by traditional publishers, or serialized in newspapers. They were sold in gay bookstores, serialized in gay newspapers, and published by gay publishers. As an example, Alison Bechdel had been doing Dykes To Watch Out For for over twenty-five years when she came to the Alternative Press Expo (APE) in the early aughts, and it was the first time she had ever been to a comic book convention. I had her on my first Queer Cartoonists Panel that year at APE, which I’ve been running ever since.

So, the queer comics underground is finally bleeding into the rest of the comic world. We’re an increasing presence at the conventions, and mainstream publishers and retailers are paying more attention. Also, the queer media ghetto isn’t self-supporting anymore—there simply aren’t enough gay newspapers and bookstores left—so as queer cartoonists we either have to find new ways to reach the queer target audience, or broaden out to a wider audience. Again, Alison’s career is a good example, as her book Fun Home was published by Houghton Mifflin and not a lesbian underground publisher, and it was named Time Magazine’s Book of the Year in 2006, which couldn’t have happened earlier. On the other hand, Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist will never probably have cross-over potential, so this model won’t work for everyone.

Johnson: What are your thoughts on broadening your content? Does that mean making it less queer?

Hall: So, as to content, I was actually just having this discussion with some queer cartoonists last night. Basically, I think we’re reacting in two different ways to this set of pressures and opportunities.

Folks like Jon Macy are interested in making their work as directly queer as possible; the tightening of the LGBT market has only galvanized him to produce material that’s sexual, positive, and important for the queer community.

Whereas folks like Ed Luce, creator of Wuvable Oaf, are making queer comics with an eye to keeping them accessible to a hip straight audience. [Ed’s] comics are not directly sexual, as he knows that lots of hard-ons and anal penetration would turn off the average straight reader, but are still very queer. [Ed’s work] deals with various aspects of queer culture—bears, body image, community, etc.—but in a way that allows a smart straight fan to be in on the jokes. I think both roads are valid, of course, and it’s exciting to watch this all play out.

To return to Macy for a moment—he’s the creator of Teleny and Camille, the graphic novel that won a Lammy in Gay Erotica, and he’s challenged queer cartoonists to add more sex into their work, and said that not having sex depicted is avoiding the reality of the gay identity and culture. But of course adding more sex narrows your audience.

Still, I think part of his position is also in reaction to the straight cartoonists who are adding more queer characters into their work; these characters tend to be “assimilationist” and non-threatening, which can be infuriating. It still falls on the queer creators to make the sex scenes, and deal with the messy identity issues and air the dirty laundry of queer identities.

Mind you, it’s wonderful that there are now queer characters in mainstream comics—gay superheroes, and a gay character in Archie, right on! But it’s still our job as queer cartoonists to do something different.

Now I would say that Ed Luce is diving into queer issues from an equally insider’s perspective as Macy, but he’s deliberately making the conversation accessible to a straight audience.

Johnson: Where do you think your work falls on that Luce/Macy spectrum?

Hall: Well, I did my stint making erotic comics, and it really—pardon the pun—opened me up as a cartoonist in a lot of ways, but now, I’m actually more interested in telling broader stories. I’d like to go back to the perspective of my travel tales for now, and simply add queer characters and themes in a smart way when they fit the larger story.

But of course, I flip-flop with my creative intentions. I’m sure that eventually I’ll be back diving into the nitty-gritty about queer identities and issues… and I’m sure I haven’t drawn the last hard-on of my career!

Oh, one other thing about this: my Glamazonia character I very much

thought of as a queer comic made by and for queers. It’s all queer culture in-jokes, for god’s sake. However, I found a broader audience for that work than for any of my other comics, and I discovered that hip straight folks love to be in on the jokes—just as long as there aren’t too many hard dicks.

Johnson: We live in the age of the confessional piece. In your opinion do you think there is a dividing line that elevates memoir based work into art?

Hall: I would say a kind of masturbatory narcissism. When the piece is only about the creator’s obsessions and internal monologues and there isn’t any attempt to broaden that out to an actual audience, that’s a problem. There are definitely memoirs that I’ve read where I’ve come away thinking “and why do I care?” Fun Home, while being incredibly self-obsessed, never lets go of the reader. Alison was always finding ways to take the incredibly detailed specifics of her life and broaden that out to something that would be of import to others.

Johnson: I know you helped organize a big LGBT Comic-Con panel this year in San-Diego. Can you just give me some brief highlights of the event?

Hall: First off, I’m always surprised by the diversity of the LGBT comic book community present at the Con: mainstream, independent, online. A huge range of people, as well as creative tastes and passions. It was really interesting and inspiring.

The panel was called Publishing Queer: Creating LGBT Comics and Graphic Novels. There were a lot of good conversations about creating new models to get content out there and how to make money from it, such as creating web-based distribution and marketing models. Traditional bookstores and comic books stores are no longer a viable option for a lot of graphic novel sales, especially ones with heavy queer content. We also discussed the viability of new LGBT-focused publishing ventures, like Northwest Press, which published my Glamazonia book.

Queer cartoonists are working really hard to figure out how to ensure people have access to their work. But I suppose that’s the battle for all creators!