Cory Silverberg : On His New Book ‘Sex is a Funny Word’ and Sex Education for Kids

Author: Theodore Kerr

August 19, 2015

“I get to present sexuality and gender in a way that I hope gives kids more options than I felt I ever had.”

As has been well problematized, our culture has a bad habit of narrowing down social change to a single moment—Martin Luther King’s “I Have A Dream Speech” and the Stonewall Riots, for example. We know these moments are the result of many lives sacrificed and dedicated to change. There are communities and schools of thought that understand and celebrate the fact that there would not have been a March on Washington were it not for Ella Baker’s one-on-ones with people in her community and Bayard Rustin behind the scene organizing. Similarly, many people can’t think about those hot nights at the end of June 1969 and not consider the liberation-of-the-mind work that gay men and lesbians across the U.S. had been doing long before that summer and the Compton’s Cafeteria riot three years earlier. We, even if it is just some of us, are getting better at understanding landmark moments are the result of connected networks of effort. But what about the other side of those tipping points? What sustains change?

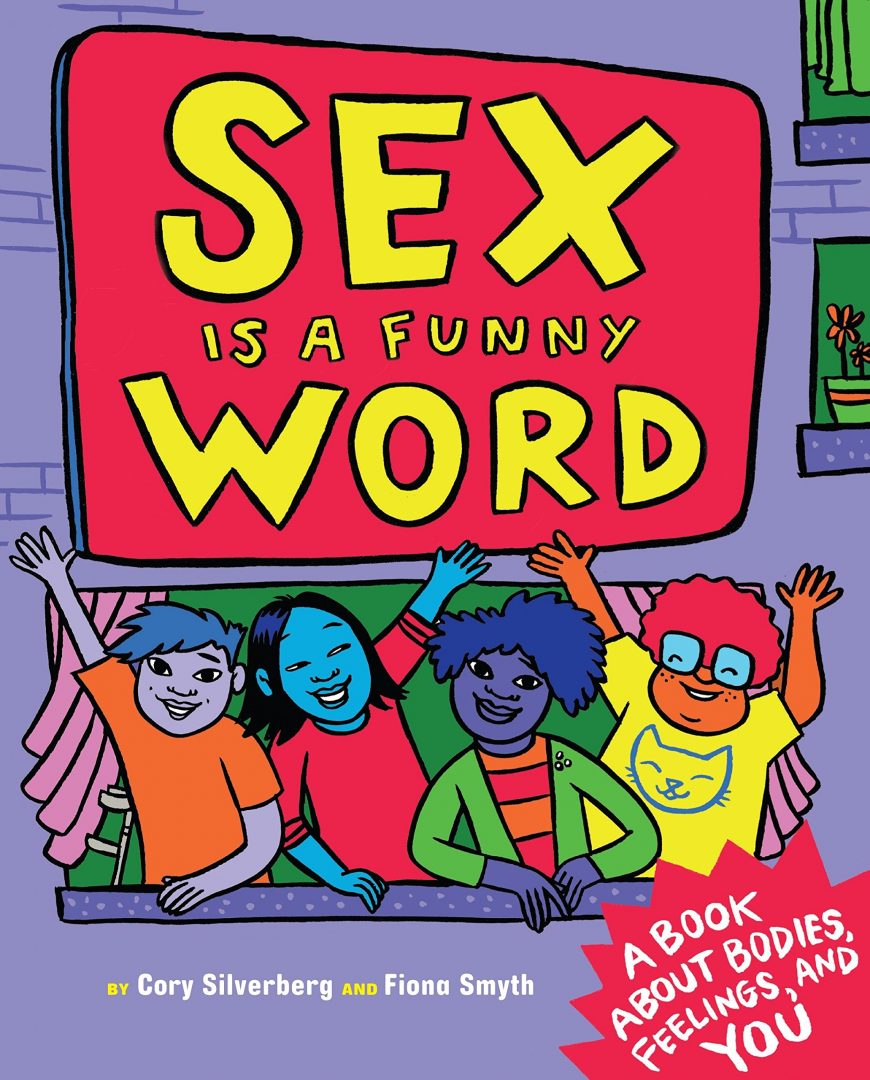

In his new book Sex is a Funny Word (Seven Stories Press), sex educator and author Cory Silverberg provides a road map to emerging and future generations to better understand one of the most dominate yet poorly understood aspects of the human experience: SEX! Building off the success of his radical approach to sex education in his first book What Makes A Baby (2013, Seven Stories Press), in Sex is a Funny Word, he synthesizes advancements made in the last few generations around gender, race, sexuality and other issues to offer a jumping-off point for parents and caregivers to talk to kids about sex. Beautifully illustrated by Fiona Smyth, the book uses comics, open-ended questions and engaging characters to help kids ages eight to ten to better understand their bodies, gender and sexuality.

Free from the casual and unquestioned sexism embedded in almost all other sex education, Silverberg’s book is an opportunity to see how gains made need to be incorporated into people’s lives to reach maximum positive impact. What good is a cultural shift if it is not experienced in public? If we are getting better at understanding that change comes via an ecology of movement through books like Sex is a Funny Word, then we also have an opportunity to see how to animate and live out that change. In the conversation below Silverberg speaks with Theodore Kerr about the meaning of the term “gender creative,” how he became a children’s book author, what justice has to do with sex, and the specific anxiety that comes for a queer person making culture for kids.

Who are you?

I was born in 1970. My mom was a children’s librarian, and my dad was a sex therapist. I know now that I was a gender non-conforming kid, but that’s not something we ever talked about. A lot of people thought that I was gay, and that would have been fine, but that’s not who I was. I identify as queer, which has a little bit to do with my sex life, and a lot to do with my gender. The word “queer” was not something that was in my life until I was fifteen or sixteen. It’s the same with the word “trans.” I have an awkward relationship to the question of who I am, but the best answer is probably that I am, apologetically, Cory.

But you did hear the words “gay,” “lesbian” and “bisexual”?

Yes, and “feminist.” There was a time when my mom taught consciousness raising groups for women. I learned about sex early on. I had all the books and privacy sex that educators today suggest would be helpful, but nothing fit. I had a hard time as a kid. I was suicidal, and a lot of it had to do with gender. Fast forward: at twenty-seven, I co-founded Come As We Are, a cooperatively run feminist, queer, sex-positive sex shop in Toronto. I was finally living in a community I felt comfortable with. I can’t imagine my life or work without that community now.

What lead you to become a queer children’s book author?

Queers around me started to have kids, including my friend Jake who is a trans Dad and whose son I am close with. One day, Jake asked, “What is the least bad book you can recommend, or better: have you written yours yet?” I realized that it would be great to write books for kids, so that’s what I did, and after two years of bad drafts, I had a pretty good book, What Makes A Baby. But at first, it was not good enough. My friend’s kid walked out during my first informal reading of it. He came back with paper, a pen and a stapler and said that he was going to write his own book!

That’s a nice critique.

Exactly. It’s one thing to say something is shit, another to work and make something better. This way of thinking is something I see all the time in my work with disability and sexuality communities, and with kids who are gender non-conforming or gender creative.

What does gender creative mean?

It’s a word that’s being used more in Canada than the U.S., where “gender diverse” and “gender independent” seem to be used more. People use them in different ways, but they are all a response to terms like “gender variant” and “gender non-conforming,” which can feel—and in some senses very much are—pathologizing.

I have mixed feelings about “gender creative,” but most parents of kids who can’t or won’t fit into the gender binary are straight and aren’t trans, and I try to use words that respect the kids and don’t freak the parents out. When I am teaching, I use lots of different terms. When you are writing for youth, you want to be descriptive, but if you are me, you don’t want to use language that feels clinical or takes you so far off your point that you lose your reader. At the same time, it’s important for kids to know that there’s a whole lot of words people use to describe themselves, so in the back of the book, I have a glossary with words like intersex and trans, but that is the only time the words gender or trans appear in this book.

Tell me about collaboration when it comes to making the book.

The illustrator Fiona Smyth and I learned a lot doing What Makes A Baby. She is an artist and a friend, and I trust her completely. I told her my mandate around gender: I don’t want it where it does not belong. That means sperm and egg are not gendered and bodies with sperm and egg do not need to be gendered. When you get to sex and making babies, you are talking about real people, so they need to be gendered. We found that we were on the same page.

Our process is that I write first; then, she does an illustration draft; I look at it, and we talk about it a lot; I show it to a bunch of kids and parents; then, we go back and forth until we have it right. With Sex is a Funny Word, there were more text edits than illustration edits. So that means I often do text edits on existing illustration drafts. To show it to kids, I zine it. I print off images, put them in a binder and read it with folks. It’s like I’m making a zine out of my own book.

There seems to be a lot of what I would call productive ambiguity around how the characters in the book are rendered.

The first question a lot of kids have is, is Zai a boy or a girl? Similarly, kids ask why Omar is using crutches. In asking the questions, kids also come up with suggestions. But so far, the characters themselves haven’t answered those questions, and it’s not my place to answer for them. At the same time, the book is about sharing lives and experiences. Look at the comic about Mimi’s crush Sam. It was important to me that Sam’s gender wasn’t announced, but I didn’t write the first draft of the comic well enough; it was clear a pronoun was missing. Many of the kids wanted to know if Sam was a boy or a girl, and they wanted to know why it wasn’t clear.

They were distracted by what they thought was being hidden, which relates to one of the things I like about the book. You draw attention to the cultural landscape from which we receive information about sexuality, hidden or not. How do you feel about this book being part of that landscape now?

It’s exciting, but also frightening. The exciting part is that I get to play some small role in these intimate conversations between kids and the adults, and that they trust enough to talk with about sex. I get to present sexuality and gender in a way that I hope gives kids more options than I felt I ever had.

The frightening part is that, of course, there will be all sorts of people who won’t like the way I’ve done this: not just conservatives who don’t think we should ever talk about sex, but folks who identify as progressive: lesbian, gay, bi people, queer and trans people who want to talk about sex and gender, but who will have problems with my choice of audience. Unfortunately, I have a strong desire to please people, and it’s terrifying to me to know that with anything you do, you’re always going to displease some people.

Beyond that, I am happy that the book will be in the world. We haven’t had a sex-ed book like this before, and I hope that many others will follow. People often think it is good to be first, but I much prefer it when there are lots of options, lots of voices and lots of books!

In describing what sex is in the book, you bring in other words not commonly linked to sexuality, including “Justice.” Why?

Justice is there because of who my earliest mentors and teachers were: disability activists and activists for people of color who are fighting ableism and white supremacy. It might seem like a strange order given that I’m a sex educator, but I did learn about disability justice and racial justice before I learned about reproductive justice.

The word sex is too big; it’s a burden we all feel. We have to unburden it. To do this, we need other big ideas that help. Justice is one of those. I needed to mobilize terms like Justice—as well as Trust, Respect and Joy—because sexuality is about small things as well as about big things. How do we prepare kids for adulthood, knowing that they may be victimized, without scaring them? One thing we can do is help them learn what trust and respect feel like.

This is something that grown-ups need to think about, too. Parents need to feel like they are trusted and respected when they are doing sex education with their kids. Many of the parents reading this book with their kids will have experienced sexual violence, and that’s not something their kids may understand or even know about. While talking about breasts and penises, kids may crack jokes. This can be hard for the parents. So I don’t see how we talk about sex without talking about other things.

Sex educators like to say people are sexual from birth to death, and I used to say that, as well. But then, I sat down and wrote a book for eight-year-olds and realized that I have no idea what that statement really means. Is an eight-year-old sexual? I don’t think so, at least not in the way that an eighteen-year-old is. They may have sexuality but, again, what does that mean? Are we talking about experiences in childhood that inform how we think about sexuality as an adult? I spent two years writing this book, and I spend hundreds of hours a year talking about this, and to be honest, I’m still very confused.

Can we have a healthy sex life without Joy, Justice, etc.?

The question you are asking is about having sex, but this is not a book about how to have sex; it’s about what it means to be sexual. But to answer your question: yes, I think you can have a good sex life with or without any of those things.

I like how the book acts as an ally. It gives the reader a sense of being witnessed.

I’m really happy to hear you say that the book felt like an ally to you, because certainly, that’s my hope: that kids will find themselves in the book, and that that experience will feel like being witnessed or validated. This book does not have a “yay for sex!” message because a lot of kids reading this will not feel that way, notwithstanding that it may be confusing for them. This is particularly true for kids who have experienced or are experiencing sexual violence. I wanted this book to be as much for those kids as for kids whose childhoods have been free of violence.

I bet masturbation is the hardest thing for parents to discuss. There it is, right in front of them on page 106, and it is tangible.

Exactly! That is why we need to talk about it. But I wonder if kids will see the illustrations in a sexual way. To make the anatomy pages work for queer and trans youth, we never show a whole body naked from head to toe. So I wonder if the images will feel more educational than sexy. I guess we’ll find out in twenty years when people who grew up with the book will come up and tell me that they masturbated to it. Actually, the images of the genitalia are one of the things I’m most nervous about in terms of reactions from adults, because we do it in a way that’s so different from heteronormative and gender normative sex ed.

It is exciting!

I am really happy that this is the first book to tell the truth about the clitoris! Even the most progressive sex-ed books for kids describe the clitoris as a small, external part of the body. The clitoris usually gets one or two lines, whereas the penis always gets at least a paragraph. For this book, I did a word count to make sure that they basically got equal billing. It feels like a small victory to be able to include the whole clitoris.

Can this book work in schools?

It could. I know some teachers who use What Makes a Baby, and they are excited about using Sex Is a Funny Word. But that’s in Canada. Public schools in the U.S. would probably not be allowed to have this book because it says that masturbation is okay and trans people are okay.

I don’t want to feel this way, but the idea of the book in school makes me nervous, like I don’t trust some adults with the authority to ask kids about touching and feeling.

Learning about sex is personal. It is not always appropriate for teachers to ask: can you think of a time when you touched a person and it was fine? A challenge I had for this book is whether I wanted to write it for the world that is or for the world that I want.

A good example is the chapter on the word “sexy.” These days, some kids use the word “sexy” all the time. They hear it in music videos, like Gangnam Style. So not only are six-year-olds hearing it; so are their four-year-old siblings. As a sex educator, I was getting this inquiry: My kid sweeps into the kitchen in the morning in their underwear doing a “sexy dance,” saying, “I am sexy.” What do you do if you are not a parent that wants to shut this down? Parents are not sure that they want their kids using the word “sexy.” Often when the word is used, it often means blond, shiny, feminine, clean.

Taylor Swift!

And Britney before her, and Madonna before her. But in many communities that I work with, “sexy” is used by people to describe themselves when they are loving their bodies and want to share that feeling with others. Radical self-love is awesome, and I don’t ever want to shut that down. When it comes to kids, we have to think about things more deliberately.

There are a few places in the book where I want to challenge parents to think about how their actions may conflict with their words, and how this can be confusing for kids. I don’t know if “sexy” is a good or bad word, but I know it can be confusing for a kid to be told that “sexy” is a bad word and then see it everywhere without any critical comment.

Another chapter where there is tension between how parents act and what they tell their kids is the one on bodily autonomy. This chapter was influenced a lot by Stacey Patton’s work, both in her memoir That Mean Old Yesterday and through Spare the Kids to intervene in Black families’ use of corporal punishment, which she ties to the legacy of slavery.

It starts with a comic where Omar is being forced to kiss relatives that he really doesn’t want to.

Parents often ask: How do I keep my kids safe? One way to help your kids stay safe is to teach them to trust their instincts, and when we make kids hug and kiss people they don’t want to, we’re teaching them the opposite. It was difficult to convey the point while not pissing the parents off too much. I don’t want to overstep my role. I just want to help bring the questions up.

Did you have any fears about being seen as a predator, being a queer person writing this book about sex for kids?

Funny you ask: Yes. In an earlier version of the book, I was illustrated as leading the kids into exploring their sexuality, saying, “Let’s go.” A friend said, “Cory, you can not lead the kids into the circus to explore their sexuality.” They were right, so I am on the page, but I stay in a box in the classroom while the kids lead the way, which is how it should be.

But to be fair, I am afraid of everything. Plenty of people already think What Makes A Baby is terrible because I took gender out of reproduction. Some Amazon reviewers say that I am warping people’s ideas of gender. Maybe I am.