Learning to Poem: The Lifespan of a Literary Crush

Author: D. Gilson

July 30, 2013

“A strange den or music room

childhood”

–Frank O’Hara

Mother works at the Aurora Family Care Center, a low and long brick nursing home on the east side of town, set back from the highway next to a trailer park, shielded from both by two lines of scrubby pine trees. The nursing home is outlined in sidewalks, the sidewalks divided into quadrants by breaks in the concrete. Like this I learn about the square, the rectangle, the line, and loveliest: the rhombus. Every morning, Alzheimer’s Room 19 marks sections of the sidewalk in chalk and every afternoon I count these. The ones that are marked and the ones that are not. She asks me about simple counting, to produce answers by way of addition and subtraction. She used to be a high school algebra teacher and it is 1989 and George H.W. Bush is president and the San Francisco 49ers just won the Superbowl and Madonna sings “Like a Prayer” which thank god is not “Like a Virgin,” and I am five years old, the unexpected son of a nursing director and a government health inspector, counting sections of sidewalk edged in brown and browning crabgrass, wearing acid wash denim jeans cinched at the ankles and waist.

When your mother is the head nurse, certain privileges are afforded you. I roam freely, areas reserved for staff—kitchen, nurses’ station, linen closet—and for residents—dining hall, game room, courtyard. The land here is parched, Father says, and the pine trees, the grasses, the shrubs and the ivy in the courtyard show the effects of a spring that never came. A warm winter that, without warning, is now an endless summer. When Orderly, the only black person in my world, takes her smoke breaks in the courtyard, I watch her five minute liturgies from behind a cluster of bushes nearby, the bushes where I bury quarters Diabetic Room 45 gives me to fetch her peppermints from my mother’s purse. By July, I will be able to buy the Pink Jubilee 25th Anniversary Barbie at Wal-Mart, the one Father refuses to buy me.

The world outside this building displays every sign of natural, brown death; the inside is all artificial, white life. White walls! White tiles! White florescent! Mother’s white shoes and white uniform and how everything on laundry day smells of Clorox! I love the Clorox smell. When I take home the Bush-Hidden Quarters, I lock myself in the bathroom, pull the stepstool to the sink and fill it with hot water and bleach, just as I have seen Mother do. I remove the Bush-Hidden Quarters from my backpack, the Kansas City Chiefs backpack I did not want, and wash them. My thumbs rub again and again across the face of George Washington. My skin puckers where it rubs the quarters, under the conditions of bleach and steaming water. In my room the Bleach-Clean Quarters gleam in the Kraft Mayonnaise jar where I keep them. The jar I keep hidden in my closet, buried amongst Legos, a baseball bat, and the My Buddy Doll that now wears the sweatshirt I have outgrown, a red hoodie that says Daddy’s #1 All Star. I will never remember wearing this sweatshirt, though pictures are able to dispel myth into fact. At night, I lie on the floor of my closet and smell the Bleach-Clean Quarters as they pass through my fingers back into their jar, as the sheen of them catches light from the flashlight I have stolen from my brother and brought into the closet. Light catches and refracts in the dark of the closet.

When your mother is the head nurse, certain privileges are afforded you. I am five years old and in those hours where my parents’ jobs overlap, I have innumerable surrogates—Line Cook, who makes his tattoo mermaid dance for me in the kitchen just off the dining hall; Alzheimer’s Room 19, Diabetic Room 45; the Designing Women—Dixie Carter, Delta Burke, Annie Potts, and Jean Smart—in the TV room; the bushes where I keep Bush-Hidden Quarters; sometimes my sister, when she does not have cheerleading or college prep or boyfriends. But my favorite surrogate is Mr. Williams.

For most of his life, Mr. Williams has been a drama teacher in New York City and back at our house, I pull the atlas, the one from State Farm Insurance, from Father’s bookshelf. This book I am allowed. Unlike the Bible, the one my mother reads to me before bed, where people die and then ride back on a cloud of black fire atop a black horse and then the black book is shut, edged again in gold and put high on a shelf named No: Do Not Touch, or Never. I open to the State of New York and there above the smallness of Syracuse is a detail of The City. I trace the island of it.

More than miles separate The City from Aurora, Missouri.

Mr. Williams is here to die. This is a nursing home—everyone is here to die and sometimes, as is the case with Mr. Williams, the dying does not come steady. Not like a train. More like a raft on a great river of white water, where the floating is lackadaisical for mile after mile and then drops, sometimes without warning, foot after freefalling foot. This is AIDS, which a five year old has no concept of; this is 1989 when few do. Mr. Williams was born near here in his parents’ bed, in a home that has long since been razed. Mr. Williams has come back to these Ozark Mountains, to the place of his birth, to die.

It is Tuesday, an afternoon in May just before summer. Like most other Tuesdays, I have watched Designing Women with Mr. Williams in the common area. I walk beside his wheelchair and like this, we travel back to his room—place of innumerable wonders among the doldrums of a Midwestern nursing home. At the end of the hall is the private suite where Mr. Williams spends his days dying, though I have little concept of this. No way of comprehension. Perhaps this is why he enjoys my company, why he invites me into the bedroom he has filled with prints emblazoned MoMA and Whitney and Guggenheim. With a throw blanket made of African tribal fabric. With a record player and neat, alphabetized rows of vinyl. Our favorite, Ella Fitzgerald. And books. I am most amazed by the books. Are these forbidden? I know few beyond the atlas and the Bible.

Yet, I know much of possibility and impossibility. I am five years old.

Mr. Williams is going blind. I read aloud to him every afternoon, practice for school sanctioned by both my mother and Mr. Williams. When I stumble on a word I do not know, which is often, Mr. Williams bids me spell the word aloud to him. He teaches me to pronounce it and gives a definition I do not or cannot understand. It is an afternoon just before summer, extra ordinary, the interim that only a balmy Tuesday in May is able to be, in a place by a trailer park and a highway, surrounded by scrubby pines and outlined in gray concrete that seems endless. I pull a book off the shelf, little with an electric orange cover.

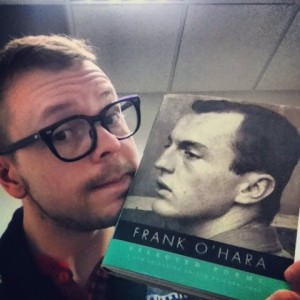

Lunch Poems, by Frank O’Hara.

I am five years old and it is the first book of poetry I encounter. The words in exotic combinations hold innumerable possibility, though I understand neither these combinations nor these possibilities yet. I am five years old and something sparks. Mr. Williams listens as I read aloud to him what Frank O’Hara has written: “Mothers of America / let your kids go to the movies!” I am, unbeknownst, in love. I am, unbeknownst, learning from my forefathers an aesthetic of queerness, a lineage, a heritage, a bloodline. Much later, in the first year of my PhD, I will read Jose Muñoz theorizing the work of O’Hara, the quotidian nature of a poem like “Having a Coke with You,” which signifies, Muñoz explains, “a vast lifeworld of queer relationality, an encrypted sociality, and a utopian potentiality.” The queer utopia is always on the horizon, Muñoz will use O’Hara to explain. That which has always been here, like O’Hara in my own life, strangely; that which has already passed, like O’Hara, tragically, on a Fire Island beach, struck by a dune buggy in the hazy morning hours of July 24, 1966; and that which has yet to come, generations of poets who will read O’Hara, who might read me and all the queer brothers and sisters who write now and have yet to write.

I am twenty-eight years old now and pull a book off the shelf, little, with an electric orange cover. When I walk to catch a bus or to buy a newspaper, I count the squares of sidewalk, adding and subtracting them in my head. I am twenty-eight years old and I live in Washington, DC. Comfortably, though it is not home. I write poems. Now I am queer and can tell you about AIDS. I can give you the definitions to words, which I do not know where—but I do know—I have learned. I am twenty-eight now and I listen to Ella Fitzgerald. Clorox is one of my favorite smells. I am twenty-eight and I go to the movies with friends or with boyfriends. Or sometimes I go alone. It is nice to be alone but not alone in the dark. I think of Mr. Williams. I think of Mother, thankful she let me go to the movies. I think of Frank.

I am twenty-eight years old and I pull a book off the shelf. Lunch Poems, by Frank O’Hara.