Paul Legault: Russian Pineapples and the 2000 Years

Author: Tony Leuzzi

June 25, 2012

“It’s interesting how appropriation—as a writing method— still has the stigma of being ‘impersonal.’ It’s actually the most personable thing you can do—in a social media sense: liking, reposting, remixing. It’s not just a form of flattery; it’s love or art’s equivalent.”

In a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Emily Dickinson wrote: “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.” As an avid reader of poetry, I often come across poems that engage me; but few make me feel as if the top of my head were taken off. I know that feeling and, as painful as it sounds, I yearn for it whenever I begin to read a book of poems for the first time. Imagine my excitement, then, in discovering that Paul Legault’s The Other Poems is such a book. Richly imaginative, often hilarious, and occasionally bizarre, this sequence of “pseudo sonnets” is one of the most original poetry books to have emerged in years. But underneath their eccentric, stylishly ephemeral surface, the poems there seem urgent, and not a little sad, I think, for they illustrate the inexhaustible ways our attempts to connect with one another are stymied by the very language we use. The Other Poems (Fence), then, not only presents an amusing, thoroughly contemporary abstraction of the sonnet form, it deconstructs a panoramic, societal longing to hear and be heard.

A finalist for this year’s Lambda Literary Award category for gay male poetry, Legault first earned strong notices for The Madeline Poems (Omnidawn, 2012). His inventive English-to-English translations of Emily Dickinson, collected in The Emily Dickinson Reader (McSweeney’s, 2012), are a valuable contribution to the field of radical translation. I met Legault in March and asked if he’d like to do an interview. He was eager to oblige in a series of email exchanges that were augmented by an ensuing phone conversation.

As Marjorie Perloff informs us in her refreshingly precise blurb for The Other Poems, your most recent book is comprised of 75 sonnets, a fact which may not be immediately obvious to most readers, since these poems abstract the sonnet form in startling ways. Each sonnet, for example, begins with a provocative couplet, which acts as an assertion or observation. This is followed by four lines of dialogue, which, though often engaging and downright amusing, tends to be cryptic. Then, four more couplets ensue: these, Perloff notes, may analyze what has come before or “spi[n] variations on its tense, absurdist drama.” Can you explain what drew you to the sonnet form for this book, and discuss some of your reasons for re-constructing the form as you have here?

I discovered I was writing sonnets by accident. I’d been working on a lot of translation projects but was eager to compose a poem “in my own voice.” The first Other Poem was actually an attempted parody of myself, limited to one page and written in a lyric mode.

But then I liked it (that’s the cruelest part). So I wrote another one in the same “form”—i.e. framed by couplets, employing seven lines of dialogue, starting with a prepositional statement, etc.

Or maybe the cruelest part was when I realized that they were all fourteen-lines-long (after writing about seven of them). Said parody went further than myself—or at least pointed out my particular brand of traditionalism.

The sonnet: English poetry’s prototype or plague. Either way, it spread.1

What is your particular brand of traditionalism?

I’m influenced by the sonnet form even as it’s something I’m resisting.

I went to the University of Virginia, which has a perceived aesthetic that is: not mine. People are often surprised when I mention I went there because my ideological brethren are perhaps more located in Brooklyn or San Francisco or Amherst.

But the conflict of these two sources—one traditional, the other “experimental”—helped to define what the latter even meant. It meant what I had to read on my own.

Do you see these sonnets as a sequence (narrative or thematic or both) or as a gathering of independent poems unified by form?

They’re thematically arranged in that they’re, in effect, all the same poem.

They’re not narratively arranged in that they’re, in effect, all the same poem.

But then I suppose repetition is a familiar narrative—if one that most often gets explored in ‘non-narrative’ media like textile design, architecture, and, yup, poetry.

In a prior conversation, you told me you wrote these poems rather quickly—one per day, I believe. What was the reason (or reasons) for this surge of creative urgency?

Speed became a theme—or was one already, but then became mine. The Other Poems were the things I was writing while writing other things, and their daily output (about one per day) didn’t interrupt my other projects—in a generous and humble way, like a background. But backgrounds are often the most interesting artistic arenas anyway.

They were partially composed that way in response to starting my first official office job. The regularity of their output became a regular comfort—and one that I missed, if I missed a day. So the editing process became more about cutting back from the 150 I wrote, down to 75 (or whatever number of them “worked”). Editing ought to be subjective. The ones that worked became the final work.

When reading these sonnets, I assume, rightly or wrongly, that many of them are built from collage methods, where you sample and appropriate others’ bits of speech, and parody tropic phrasings from other poems. You told me poet Billy Merrell provided you with the hilarious final line for “The Things You Find Underwater.” And in a few places I could have sworn you were citing a fortune cookie. Was collage a frequent compositional method? If so, why? If not, what were some of the methods you used?

Billy did inform me that “An octopus’s butt is also its mouth.” He also took my author photo and designed the cover. He’s a good friend and a constant companion in my 9-to-5-life at the Academy of American Poets, so, inevitably, he’s in the book. In fact, a lot of my friends make “appearances,” though I didn’t do a good job of cataloging everything I stole from them. I guess the book is the best catalog I could come up with.

It’s interesting how appropriation—as a writing method—still has the stigma of being “impersonal.” It’s actually the most personable thing you can do—in a social media sense: liking, reposting, remixing. It’s not just a form of flattery; it’s love or art’s equivalent.

Acknowledgment pages make me nervous, but if there were a proper one it’d be as long as the book—each character’s line requiring a line of acknowledgment. Maybe it’s helpful to point to the book’s epigraph here, since I put it there to be pointed to. Anyway, bpNichol said it better than me when he wrote, “The other is emerging as the necessary prerequisite for dialogues with the self.” Though “the other” might not seem like a term of endearment, it’s what leads to everything.

Certain images recur throughout. For me the most evocative of these was the hat. What do hats mean to you and why do they make such frequent visits in these poems?

Hats are funny. And removable. They’re the easiest way to make something look human. Put a hat on a dog, and suddenly you’ll start to address him formally: “Why, hello there, Mr. _____,” although that dog simultaneously illustrates the absurdity of said formality.

Abraham Lincoln became a hat. Napoleon did that too. Then Marianne Moore stole his hat, so she could become one.

In high school, when I brought friends over, my father would enter the room in a hat that made it appear as if there were a nail going through his head. It was a kind of test. I suppose they usually passed, though the examination criteria seemed a little strange—if extremely human.

Hats are as meaningless as ceremony. Which is to say they mean symbolically.

But now I’m just talking about hats, not poetry. Except I guess I’m talking about both.

Another recurring motif is a voice, which the cover art refers to as an opening in the ground. Who is this voice and what are some of your reasons for creating it?

C. F.’s comic series POWR MASTRS features a non-visible character (indicated by a brick hole in the ground with a speech bubble coming out of it) who is perpetually trapped inside of a (bottomless?) pit. That’s what the cover art is taken from.

I wouldn’t say that character’s mine or is even in the book, except that the idea of a person whose only characteristics are conveyed via language resonates with all the speaking roles in The Other Poems. They too aren’t real except when given imaginary features. But those imaginary features explore language in as real a way as the objects/people/concepts they’re based on.

This interview will be published in The Lambda Literary Review, an LGBT publication that focuses almost exclusively on LGBT-referenced literature from many genres. Although you are a gay man, and although many of these poems make sly “in” jokes certain readers might recognize as gay, I would not presume you are writing solely for a specifically gay audience. Who do you imagine is the ideal reader of these poems? Who was your real or imagined audience while writing them?

No one writes solely for a gay audience—whether they want to or not. But I like thinking of The Other Poems as a queer text—in the same way Berrigan’s Sonnets or Berryman’s Dream Songs are. They queer their audience—as well as their authors—no matter what their practiced sexuality might be. A book like Frank O’Hara’s Selected Plays may be written by a gay poet, but it queers us/himself in a similar way to those straight men’s: aesthetically.

Of the two options you put forth, I guess I prefer an “imagined audience.” It’s useful to think of one’s influences as playing the role of “audience,” even though (because?) they might be dead. But my influences aren’t all imaginary: I write for myself, and my friends.

Your previous book, The Madeleine Poems, was a finalist for the Publishing Triangle’s 23rd Annual Award for Gay Male Poetry. The Other Poems was a finalist for this year’s Lambda Literary Award category for gay male poetry. Besides these two considerable achievements, it’s hard to find a good deal of commonality between the books. What might you say are some links between the two? What are some of the differences?

Similarity: “Madeleine as James Dean and the Whale” was, chronologically, the last Madeleine Poem I wrote. Its most obvious connection to The Other Poems is the use of dialogue. That led to that.

Difference: My first book was an attempted/failed portrait. But whereas The Madeleine Poems sets out to portray a persona, The Other Poems doesn’t even try. This time, I kind of reveled in the inevitability of that failure, and peopled it.

You are the co-founder and co-editor of Telephone Books, an all-translation press. Although the sonnets in The Other Poems are your own, I was wondering if, conceptually, translation is at all brought to bear on how these poems were written. I was also wondering if you could discuss how a broader notion of translation informs the way one might read them.

Yes. In fact, the last five poems in the book are actually “translations” from the poet Uljana Wolf—into pseudo-sonnet-dialogues. For me, what was interesting about the process of those translations—and their eventual inclusion in The Other Poems—was how it provided an intimate/direct audience (Uljana) but also an indirect exploration of ownership.

Here it might be useful to single out Uljana Wolf’s poem “(z)et (z)oo (z)oo” (and its corresponding poem “[not from] [not a] [not where they leave them alone]”

Wolf’s reads:

(z)et (z)oo (z)u

mister, we’ve been to the zoo, but it was closed. wir wollten die entblößung unserer zähne trainieren, studieren das stimmhafte sehnen zum beispiel der zebras, weil alles zueinander anders sagt, mal so und mal zoo. zuletzt entdeckten wir, verzagt am zaun, ein echsenset. wir nannten sie ginger und fred. it seems, you said, they never called the whole thing off. das gab uns reichlich stoff für den heimweg.

Susan Bernofsky’s more “faithful” English translation of the same reads:

(z)et (z)oo (z)u

mister, we’ve been to the zoo, but it was closed. we wanted to practice baring our teeth, to study the voiced musings of the zebras, say, since everything says everything some other way, or two, or zoo. at the gate’s azimuth or zenith we espied a set of lizards. we dubbed them ginger and fred. it seems, you said, they never called the whole thing off. and this food for thought fed us all the way home.

Mine reads:

[not from] [not a] [not where they leave them alone]

At the zoo, them being the animals at the zoo,

it being the zoo, it was closed.MISTER: What’ll it be?

TEETH: To be a train

that’s been let out.

ZEBRAS: There was a kind of zoo once.

ZEBRAS: Now there is just this zoo.Everything is its separate everything.

We discovered the lizardsare not exactly dancing.

GINGER: Let’s call the whole thing—FRED: No.

YOU: I like youlike them

but on the way home.

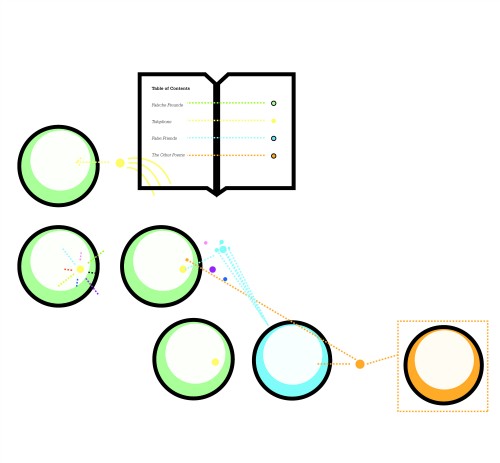

I thought a visual description might be useful to describe my experience with this poem—and add another level of “translation” (click to enlarge):

1. Uljana Wolf’s poem first appeared in Falsche Freunde (kookbooks, 2009).

- Sharmila Cohen and I approached Uljana to have a team of ~10 translators write versions of her poems for Telephone.

- One of those translators was Susan Bernofsky, who later published a translation of the whole book for Ugly Duckling, as False Friends (2011); its appendix contained a number of Telephone offshoots, including “[not from] [not a]…”—

- —which was later published in The Other Poems, as a poem “by me.”

To say it’s co-authored is to say that it’s simultaneously an original poem (by me) and a poem that was already originally written (by Uljana Wolf). In The Other Poems, many of the objects/subjects of Uljana’s (TEETH, GINGER, FRED, etc.) are given speaking roles. They take the agency away from the narrator (i.e. poet). That’s what I was trying to do with all of The Other Poems. Though here, because I’m acting as “translator,” the notion of removing agency from the dominant voice is less humble, since the target (author) was Uljana.

Her language is given a speaking role—

“since everything says everything some other way, or two” (Wolf via Bernofsky)

All written works gain new lives through various modes of representation—from a rough draft, to print, to a web-life (via an online publisher, social media, gmail (via a mac vs. a PC (via one country vs. another…))) That Uljana claims this poem as much as I do doesn’t ruin either claim’s validity—but doubles it. The original exists, unharmed—in fact, it exists again in this very article.

In “(z)et (z)oo (z)u”, Mister is somebody we want to address (“Mister, we’ve been to the zoo, but it was closed”)— so, in my version, MISTER asks: “What’ll it be?” Timothy Donnelly, in the same Telephone issue, translates the line as “Dear Committee: What a clusterfuck.”

There is no writing without change, and it was the idea of all these things speaking at me, as opposed to the other way around, that drew me to the dialogic form. It matched my experience. EXPERIENCE: You match me.