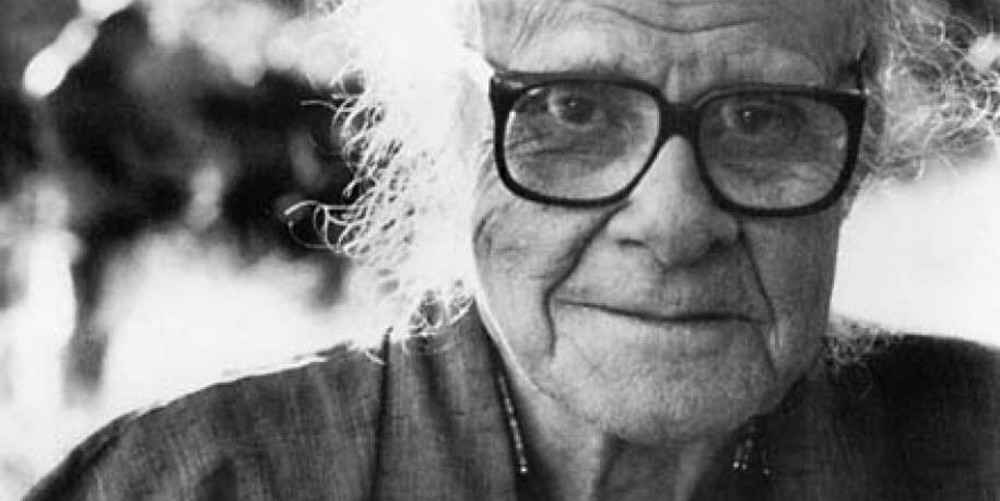

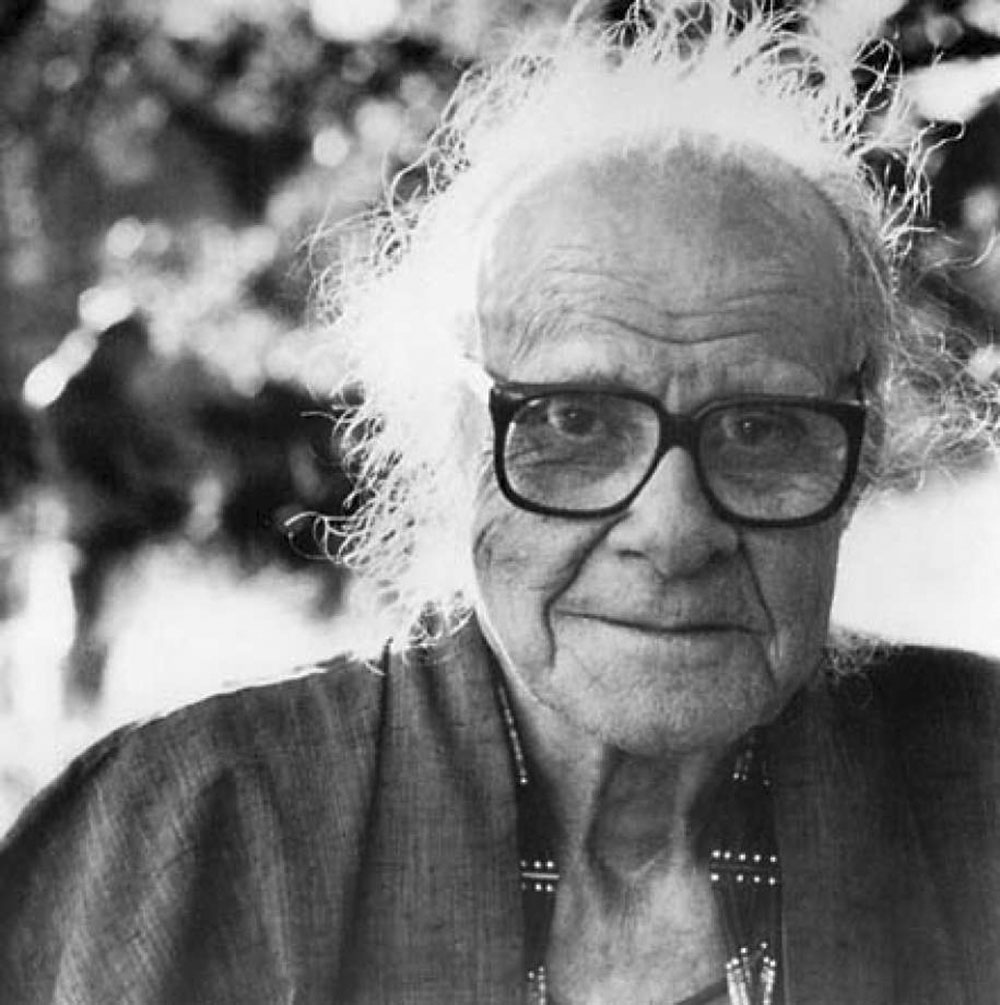

On Meeting Harry Hay

Author: Donald Weise

May 1, 2014

Years ago, right after I’d graduated college, I used to get my hair cut in the home of a “little fairy” (his words) who lived in the Melrose district of Los Angeles. I’d found Tom in the Gay Yellow Pages shortly after coming out, when I felt everything in my life, including my barber, had to be gay. As if I needed to look hard to find a gay hair stylist in Hollywood. His phone number was YES-SIR1, and he answered the phone every time with those exact words, “Yes, sir,” rather than hello. Having never met a leatherman, much less been inside the home of one, I thought at first he was just an exceptionally polite barber; his life as a submissive was soon revealed and I was officially in on the joke. One day as he cut my hair, I noticed an old man across the street wearing a big, floppy sunhat and shoving a push mower across his front lawn. I asked Tom, with a gesture outside, “Who’s the old queen in the crazy hat?” Tom looked across the street and said, “That’s Harry Hay. He started the gay rights movement a million years ago. You ever hear of the Mattachine Society? That was Harry. He comes over and looks at porn on my computer.” Now, you’d think being told that the man behind the push mower had actually started the gay rights movement in the US would have impressed me and maybe even left me in awe, but it didn’t. I was just twenty-four and to me Harry was an “old queen,” something I was afraid of one day becoming. Now that I stand at the threshold of that reality, if in fact I haven’t already crossed it, I no longer am. I’d see “the old queen” again sometimes when I stopped by Tom’s house. There was something about the hat that made me think of Harry comically, even though I saw him wear it just once. I don’t know at what point I realized the magnitude of Harry’s place in history, but I can tell you he no longer represents a comedic “character” to me.

As I got older and my interest in history and writing about it became serious, I developed a true appreciation for early freedom fighters. Harry took great personal risks by creating a refuge for gay people during an era of intense sexual repression and political persecution, and it’s because of freedom fighters like him that we enjoy whatever freedoms gay people have today. But as much as I admire Harry and the men and women behind the burgeoning gay rights movement of the 1950s, I admire African American freedom fighters of the period even more: A. Philip Randolph, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, Malcolm X, and Huey P. Newton among them. It’s not that I don’t relate to early gay activists or value their contributions, I do, but I identify more closely with the work of these black leaders. Perhaps because their movement originated in slavery, and it’s been nothing but a battle for equality ever since. However you explain it, this affinity led me to first start writing about black social protest. Although I don’t hold a degree in African American history nor do I have formal training as an American history scholar, I can write and talk about the 1950 to 1980 period of African American history as though I had. For years I’d read and studied extensively the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Liberation Movement that followed and even became acquainted with some of the players in these movements. My readings in African American studies made me not exactly an expert but enough of an authority that I could speak in public on the subject if anyone asked–and no one did.

As my knowledge of African American history grew, I began to feel confident enough to write historical introductions to the black history titles I edited and published. One of these books, an anthology of 100 years of black gay and lesbian fiction (yes, it goes back that far), required a lengthy, scholarly introduction to the mid-century period. I needed to tie together African American history, gay history, women’s history, and black gay history into a single narrative, no small feat. Because when it came to writing about black gay life during this era, one of the problems, I discovered, was that resources were seriously lacking when it came to documenting the role of blacks in the gay rights movement of the ‘50s. Considering the realities of racial segregation in the US at the time, it wasn’t hard to imagine that a black gay person might not exactly dive into a room of white strangers (who called themselves “homophiles” no less) regardless that he or she shared their sexual orientation. It was still the 1950s and still a room full of white people. But is it that simple? In spite of the fact that racial segregation–and worse–had plagued African Americans for centuries, did blacks avoid early gay rights groups on grounds of race and perhaps concerns over safety?

To answer this question, I decided to start by looking up the first gay rights group that went on to become a national organization: the Mattachine Society, co-founded in Los Angeles by Harry Hay and Rudi Gernreich in 1950. The group viewed homosexuals as a cultural minority akin to blacks and to that end organized political and social programs aimed at empowering and redefining what it meant to be gay. This was a journey back in time for me, and it proved to be a very short trip. Nothing I saw in books or online or in library archives made any mention of blacks being involved with Mattachine in the ‘50s. Los Angeles, however, is a racially diverse city with a sizable black population, even back then, I imagine. Although the Civil Rights Movement had not yet swept the country, it seemed to me that some black gay people would nonetheless socialize and engage politically around their sexual orientation, no matter that it might be within a group as white as the Mattachine Society appeared to be.

Having gotten nowhere in my research, but feeling obligated to address Mattachine in my essay somehow, I decided to go directly to Harry, who now lived in San Francisco, and ask him: “Were there black people in your group in the beginning and if so, who were they?” History isn’t always within an arm’s reach like that, and for the longest time I wasn’t even aware that he lived a few blocks from my apartment. I used to walk past his place all the time, though, and you couldn’t miss it: His home was purple with a large marijuana leaf painted across the fire-engine red garage door. That kind of thing stood out but not by a lot considering this was the Castro. (Someone later told me that the building was actually owned by an elected official, an advocate of pot, clearly, who let Harry live there rent-free.)

I wasn’t about to call up the old days, when I thought Harry was a daffy old man in a funny hat, as I now needed him to answer questions for my essay. Somehow I knew he wouldn’t be charmed by my recollections. I walked over to his house and knocked on the front door. His partner, John Burnside, opened it, and I told him who I was and why I’d come. John very graciously waved me in. You entered through the kitchen, and as John led me into their home, he warned me that Harry was in bed and so frail that he was on oxygen and likely to tire quickly. He was almost ninety after all. I assured him that I had just a few questions and would be out of there in no time. I don’t remember Harry lying in a bedroom but in the living room, on a bed that had been installed there. He was awake behind the oxygen mask and I shook his hand. My arrival seemed to bring him to life a little more. His eyes were alert, his voice clear once the mask had been removed, but removed only to speak. It was exactly like visiting your grandfather in a convalescent home and elicited the same feeling of helplessness. Sitting in a chair beside him, I thought, “What if somebody somewhere has already written on this topic but I just didn’t see it, and here I am putting out this sick, old guy who can barely breathe?” But he was ready, he said, despite his condition, to report on anything I wanted to know.

I started by asking whether black people came to the Mattachine Society in the beginning. I was most interested in the early years, since they pre-date the 1954 Montgomery Bus Boycott, which is considered the birth of the modern Civil Rights Movement, and because blacks would be taking a greater risk crossing color lines at that time rather than in, say, 1965. In fact anyone would have been taking a risk by coming to Mattachine. People lost jobs and custody of their children over their sexual orientation back then. Despite his leadership position, Harry himself was ejected from the group in 1953 because members felt his Marxist past was too controversial and threatened Mattachine’s reputation. As for African Americans, he told me there were two black men in the organization near its inception, though he couldn’t remember their names. It didn’t matter, really, since people didn’t use their actual names at meetings anyway. One of the two men dropped out almost right away, he said, the other stayed on but not for long. I asked if he thought racial segregation of the era had an influence on whether African Americans would attempt to take part in what was essentially a group of white men. He misunderstood the question and said, “You really don’t know much about the Civil Rights Movement, do you?” I answered a little defensively, “Actually, I do,” proud of my background but trying not to sound confrontational about it.

We went on to talk about the visibility of black gay men on the scene when he first became politically active and which of these men, if any, he happened to know. He named Countee Cullen, the celebrated Harlem Renaissance poet. Harry used to see him in Central Park in the ‘30s or ‘40s, he told me. “What do you mean?” I asked, wondering where you might come across someone famous in the park. “What was he doing…like, reading a newspaper?” I don’t know whether talking about his past gave him renewed energy but Harry became coy here and said with a grin, “No, darling, we were cruising.” Maybe it was the moment of levity that allowed me to ask the next question, rather off-handedly and thoughtless in a way, and it came out sounding glib unintentionally: “So, what was it like to be a gay man in the nineteen-thirties and -forties?” It was almost as if a pall had come over him. His expression was suddenly grave and before he said a word I knew I had entered rough territory. Harry took off the oxygen mask, almost as much for emphasis as to speak, and said, slowly, “You cannot imagine the terror.” His look was similar to the one I’d seen on Gore Vidal’s face a few years before when he told me about a gay sting operation during World War II, when he was stationed in the Aleutian Islands. Hundreds of servicemen were set up, he said, rounded up, and shipped out to be court-martialed out of the service for being gay, even though Vidal believed most were not gay. I don’t imagine one usually saw Vidal with a look that said, “You cannot imagine the terror,” but that was about as close as it came I’d guess. Listening to Harry, and being reminded of Vidal, I couldn’t help but wonder: If the nightmarish realities of the era could still shake these gay warrior-types after decades, how would someone ordinary like me have survived them? I probably wouldn’t have.

In spite of the hour we had together, Harry seemed to be hanging right in there, showing no signs of tiring. Well, he was lying down. Once the interview was completed, I thanked him for his comments and stood to leave. Before going, though, I told him I lived nearby and that if he ever needed anything (groceries, medicine, whatever), he should call and I’d bring it over. I handed him a slip of paper with my name and phone number on it, which he gave to John, who had now rejoined us. I thanked Harry again and said I’d bring him a copy of the book when it was published. I left wondering how he could live that long.

But gay activist-leaders of the old school can be tough and enduring (Del Martin, Phyllis Lyon, Barbara Gittings, Frank Kameny among them), and Harry was no exception. I heard he had made a local public appearance, and so now that he was in better shape I decided to take him flowers and say hello. John answered the door again. Harry had several male visitors this time, and I was surprised to see him looking so much better than when we’d met just weeks before. Frail, yes, but on his feet and entertaining people. Holding out the bouquet, I said once more how grateful I was to him for taking the time to speak about Mattachine. I don’t know if he remembered who I was but he came over and thanked me, quoting grandly about “the brotherhood of man,” which sounded like a line from Walt Whitman, but given the fact that my knowledge of Whitman’s writing is confined to The Dead Poet’s Society, it could as easily have been from the musical How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. The combination of Harry’s looking so much healthier and the unexpected poetry recitation left me for a second at a loss for words. I noticed the slip of paper I’d written my name and phone number on fastened to the refrigerator door with a magnet. “So he really might call me after all,” I thought. I can’t tell you why but I wanted to be of use to him, probably because he held such a historic place in our past and I felt indebted. I told him I was about to leave on a trip for New York—the one in fact where I would decide to move here—and that I looked forward to seeing him when I returned. I said goodbye, pleased to know he was in improved health. Not long afterwards, he died.

As I was finishing this essay, my computer pinged, letting me know a new message had arrived on the gay dating (okay, sex) site. “Hey, man. Good morning. How’s it going?” someone named Gerardo wrote. “Good,” I replied, noncommittal since there was no picture of his face to match the impressive torso shot posted on his profile, “just doing some writing.” About a minute later, another message arrived: “Sounds good. What are you writing about?” I kept it going, waiting to see if he’d unlock the private pictures he had hidden. “Gay history in the nineteen-fifties. About Harry Hay who started the gay rights movement,” I told him. “It sounds very interesting,” he said. “I don’t know much about him.” “I didn’t either,” I answered truthfully, “and that’s part of what I’m writing about. For all his accomplishments he’s not as well-known as he should be, even by gay people.” Silence followed and for a moment I thought my visitor had moved on to more “direct contact” with someone else. Finally there came a new message from Gerardo: “It’s important to know our history and to know those who opened the way for us to be more free and proud. Nice work.” Yes, nice work indeed, Harry.