Mark Merlis: On His New Novel ‘JD,’ His Writing Process, and the Autobiographical Details in His Work

Author: Christopher Bram

March 16, 2015

“I don’t know how other people work, but all my work is trial and error. You start out on the path to the book you think you want to write, and you may run into a dead end—like the dumbest rat in the maze—or you may find an opening to a vista you never imagined.”

Mark Merlis is one of my favorite contemporary novelists. I will read anything he writes. I’ve been reading him passionately ever since his first novel, American Studies, came out in 1994. Reeve, an older gay man hospitalized after a gay bashing, remembers his difficult friendship with a famous English teacher of the 1950s. Sentence by sentence, it was the most beautifully written first novel I’d ever read; the prose took one deep into the gay world of another era. Merlis followed that with something very different: An Arrow’s Flight, in which he ingeniously mixes the Philoctetes story from ancient Greece with New York gay life in the age of AIDS. We get gods and goddesses, aircraft carriers and archaic armor, high priests and go-go boys. It begins as a stunt and a comic tour de force, but gains real emotional weight and power as it progresses. His next novel was the very real, very personal Man About Town, the humorous story of a middle-aged bureaucrat hunting for the model from the swimsuit ad that first made him aware of his sexuality when he was a teenager. It’s really the tale of a man looking for his youth, but also an exploration of how much the gay experience has changed in fifty years.

Merlis’ new novel, JD, coming out this month from the University of Wisconsin Press, is a return to the literary and historical concerns of his first book, but it has something new; he never repeats himself. His chief narrator is Martha Ascher, his first female protagonist, and she’s a remarkable character: aware, tough, moral yet culpable. Martha was once married to bisexual writer and social critic Jonathan Ascher, important in the 1960s but now dead and mostly forgotten. (The title comes from the title of his most famous book and is short for “juvenile delinquent.”) She finds herself caught in the life of the dead when a biographer begins to explore the past Martha has carefully buried, including memories of their son, Mickey. Martha finally reads Jonathan’s diary, something she has avoided the temptation to do for years. The diary provides a second narrative to the novel. The result might be Merlis’ best book yet: an intense, detailed portrait of a marriage set in the New York literary world at the time of the Vietnam War. It’s as gorgeously written as Merlis’ other books, but also very sexy and very dangerous.

I recently spoke with Merlis via email about his new novel, his beginnings as a writer and his double career. He is as articulate and surprising online as he is on the printed page. Merlis is sixty-five years old and lives in Philadelphia with his husband Bob.

What gave you the idea for JD? It’s clearly fiction, but did real people inspire it?

This is a question I love to duck, so thanks for bringing it up right away! The central figure in the novel, Jonathan Ascher, was drawn at the start from Paul Goodman, the radical social thinker and poet who was famous in the 1960s and whose angry, yearning vision of a society fit for real humans has never stopped haunting me. Readers may spot other characters who resemble Gore Vidal, Frank O’Hara and Philip Johnson. I wanted to write about these guys as a way of getting a handle on the world I grew up in during the ‘60s and ‘70s, and how we got from there to here. But real people don’t work in a novel; pretty soon, the story wants to go somewhere the character won’t take it, and it is the character who must give way. So the people in the book wind up wildly divergent from—and at the same time still recognizably akin to—the people they were based on. One of my earlier novels had a character based on a real-life figure, the Harvard professor F.O. Matthiessen, and I was pilloried by some critics because my character did things Matthiessen would never have done. All I can say this time around is, yeah, Jonathan does, says, thinks and feels stuff Paul Goodman wouldn’t have. Jonathan was, in your word, inspired by Goodman, meaning Goodman lent him his first breath. But then, he had to learn to breathe on his own in the artificial air of the novel, and thus, he became someone completely different.

You have two first-person narrators: Martha, the wife, in the present; and the journal of her husband, Jonathan, from the past. They twine together beautifully, like a double helix. Did that come easily, or was there a lot of trial and error in orchestrating the two voices?

I don’t know how other people work, but all my work is trial and error. You start out on the path to the book you think you want to write, and you may run into a dead end—like the dumbest rat in the maze—or you may find an opening to a vista you never imagined. Martha in the present day was just going to be a framing story, with almost the whole book devoted to her husband’s journals. But as I started writing down the scurrilous things Jonathan had to say and the lamentable things he did, I couldn’t help imagining how Martha, reading all this, might respond. So I started letting her interpolate her own thoughts here and there, and pretty soon, the book turned into a contrapuntal two-part invention. There are trade-offs, I think, in this way of working. One of the great joys of writing is finding yourself going somewhere unexpected. But at the same time, you never get where you meant to go: hovering next to the finished work is the ghost of the work you never got around to. And of course, your computer is littered with many, many megabytes of prose that don’t fit in the revised outline and wind up homeless and unloved. (I’ve got one nifty passage that’s been on my successive hard drives for thirty years and keeps trying and failing to sneak its way into a book.)

You grew up in Baltimore, right? Where did you go to college, and what did you study?

I grew up in Baltimore, came out there, met my husband at last call in a dive bar called Leon’s (which is still there!) and finally left it in my late thirties. I guess most people now think of Baltimore as the burned-out backdrop for The Wire, or as the quirky blue-collar town of John Waters’ movies. But I grew up in the Cheeveresque northern section called Roland Park. My block was the one with all the Jewish doctors (including my father), so I was in that Aryan world, where girls still had coming-out parties and boys were blond lacrosse players, without being part of it. Rather like John O’Hara, I regarded the WASP cosmos with a mix of envy and contempt. I’ll leave you to tease out how this is manifest in my work.

I went to Wesleyan, in Connecticut, just at the time when frats and beer parties dissolved in a haze of pot smoke. I didn’t learn much; I mostly just spent my college years brooding about those unwelcome queer feelings that I couldn’t shake off. I spent my junior year at Smith, during its very brief experiment with coeducation. I had thought, in a place with 2400 women and twenty men, I would find the woman who would cure me. Of course, I spent the year looking at the other nineteen guys. But my real education also began at Smith, especially my introduction—through my lifelong mentor Robert Petersson—to the poetry of ecstatic longing that underlies all my work.

After college and three days of law school, I wound up working toward a doctorate in American Studies at Brown. Like Reeve, the hero of my novel American Studies, I spent my days moping and reading old bound volumes of the New Yorker, and my nights striking out in the dank sepulchral gay bars of downtown Providence. Then—again like Reeve—I dropped out and tumbled into the bureaucratic life that ensnared me for the next thirty-five years.

Did you always want to be a novelist, or did you not get the itch until later in life?

I got the itch—a much more accurate word than the haughty vocation—in my teens. It was, precisely, an itch to be a novelist, rather than an itch to write anything in particular. This was in the days when novelists were at the center of the culture, showing up on Johnny Carson and the cover of Time. I finished my first novel when I was twenty-one, landed a well-known agent and got very nice rejection letters from famous editors. The second novel got fewer and gloomier letters, while the third and fourth went straight to the desk drawer. All these early novels were deeply closeted fictions in which (as McCarthy said of Hellman) every word was a lie, including and, and the. I stopped writing for ten years or so, until I was finally ready to write a book true enough to be published.

You are admired by myself and other writers because you are a successful novelist who’s also had a successful full-time career in another field: health. How did you manage that?

I just stumbled into it. After I dropped out of graduate school, the only job I could find was as a clerk in the Maryland health department. I was just biding my time until I became a famous novelist, but as long as I had to be there eight hours a day anyway, I figured I might as well actually do the work. This was so unusual in that catatonic realm that within a few years, I was making policy, and pretty soon, I was working for Congress, advising on topics like health care reform, AIDS funding and technical issues in Medicare. For a while, this was pretty absorbing, insomuch that I gave up writing fiction. Then, when I was forty, I was ready to begin again. Like Trollope, I wrote for an hour or two every morning before heading out to the office. When I retired a couple of years ago, just when I was really getting going on JD, I figured that at last I’d be able to write all day. But it turned out I could only write for an hour or two anyway. I don’t know how you guys who work all day keep your concentration.

I can’t speak for the others, but I’ve found that I do good work only in the first hour and the last hour. The two or three hours in between are usually spent rewriting the same page over and over again while waiting for the muse to return. In three of your novels, you’ve written what I think are intimate epics. American Studies, An Arrow’s Flight and JD are all meditations on recent American history. But your previous book, Man About Town, was more private and personal: the simple tale of a middle-aged man looking for the source of a sexy ad that meant the world to him as a teenager. Am I right in thinking that this is your most autobiographical novel? There’s a lot of great detail about life in Washington D. C. It might be the best Washington novel I’ve ever read, and I wrote one myself. It’s more fun and more real than anything by Ward Just or Allan Drury. Are you writing about your own work experience there? And was there an ad that spoke to you when you were growing up in Baltimore?

Of course, all my novels are somehow autobiographical—Madame Ascher, c’est moi, not to mention Reeve—but it’s true that Joel Lingeman in Man About Town had my actual day job, much of my boyhood and some aspects of my sensibility. So yes, that was my most autobiographical novel, except that I left out everything about myself that I’m ashamed to reveal or afraid to face, which is why Man About Town is the weakest of my published novels, and why I’m not likely to go so far in the direction of autobiography ever again. I’ve been reading lately that fiction is dead and that relentlessly self-revelatory writers like Karl Ove Knausgaard and Rachel Cusk are the wave of the future. I guess I’ll just accept obsolescence.

As far as Washington books go, I loved your novel Gossip and have always been a secret fan of Drury’s Advise and Consent (though not of his later, more openly fascist novels). I guess what’s different about mine is that it centers on someone who’s at the fringe of Washington life. The hero is just close enough to the action to know that something is going on, but not close enough to know just what that something is. That was how it felt for me in my Washington years: I got to go to a lot of closed meetings at which decisions seemed to be made, but I was never in the pre-meeting at which the principals actually made up their minds.

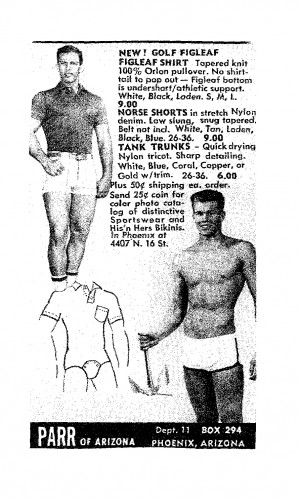

The ad you mention, for swimsuits by Parr of Arizona, showed up in about 1964 in the back pages of Esquire and the great, forgotten magazine Show. The Parr boy was famous among my generation: I know he caught the eye of Joe Brainard, Ethan Mordden and Andrew Holleran, among others. (Here he is, with his silly anchor, if this isn’t too racy for Lambda.) It wasn’t just his beauty that held me, but the way he seemed at home in his body in a way I could never be. Bernard Cooper has written eloquently about the way young gay boys have their very bodies stolen from them. He recovered his; I never quite did. So there’s a little revelation for you, which is as much as I care to supply.

The ad you mention, for swimsuits by Parr of Arizona, showed up in about 1964 in the back pages of Esquire and the great, forgotten magazine Show. The Parr boy was famous among my generation: I know he caught the eye of Joe Brainard, Ethan Mordden and Andrew Holleran, among others. (Here he is, with his silly anchor, if this isn’t too racy for Lambda.) It wasn’t just his beauty that held me, but the way he seemed at home in his body in a way I could never be. Bernard Cooper has written eloquently about the way young gay boys have their very bodies stolen from them. He recovered his; I never quite did. So there’s a little revelation for you, which is as much as I care to supply.