Sherlock Holmes: Queer, Straight, Neither?

Author: Cathy Camper

March 8, 2010

I don’t remember how I discovered Sherlock Holmes, but I remember when—I was 10 years old—and I remember why—I was one of the taller, brainier kids in my class, and he was a perfect role model. I doggedly read my way through The Boys Book of Sherlock Holmes, despite classmate ridicule (“You’re a girl!”) and the baffling behaviors of Victorian London (when I questioned my mom about Holmes’ cocaine usage, she replied, “Oh, that’s just something adults sometimes do to feel good.”)

I was never a Holmes scholar, but I do keep up with him, a literary pal like Harriet the Spy and Fantomas whose acquaintance I value.

I was intrigued by Robert Downey Jr.’s claim that he played Holmes as queer in Guy Ritchie’s latest film “Sherlock Holmes,” followed by the quick denial of Andrea Plunket (who claims U.S. rights to the Holmes stories). But the film was disappointing; it had more in common with clichéd buddy movies like “Batman,” “48 Hours,” and every other film aimed squarely at the wallet of 13-year-old boys than it did with Victorian shirt tuckers. If anything, Downey played it like the life-style of Robert Downey Jr. via “Fight Club.”

Just because he takes off his shirt it’s supposed to be queer? And while we all know that Holmes occasionally used weapons or his fists, wasn’t the whole point of the stories that he triumphed with his brain?

Like many single unmarried adults, Holmes’ sexuality gets questioned. The first nudge-nudge-wink-wink always points to gay, though as often as not it may mean a person is bisexual, asexual, complicated or just plain lonely. As Laura Miller point out, in her adroit discussion of Holmes “— there is something decidedly unconventional about the sexuality of Holmes and several other popular fictional detectives (Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple and Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe spring to mind).”

So what did Arthur Conan Doyle have in mind when he created Holmes? He claimed to have based his detective on Dr. Joseph Bell, on of his teachers at medical school. Doyle himself bore more resemblance to Dr. Watson, a mustached doctor who was also a soldier. But his official web page contains some intriguing tidbits. For instance, this account of Doyle’s meeting with Oscar Wilde:

Oscar Wilde appeared to be a languorous dandy, whereas Conan Doyle in spite of his best suit, looked somewhat like a walrus in Sunday clothes. Yet Oscar and Arthur got along like a house on fire. “It was indeed a golden evening for me.” Conan Doyle wrote of this meeting.

Later in the biography, Doyle’s liberal views towards homosexuality are mentioned again:

Two years later, Conan Doyle’s acute sense of justice was awakened again and made him rise to the defense of Sir Roger Casement, an Irish diplomat accused of being “the foulest traitor who ever drew breath.”

…

Conan Doyle almost succeeded in sparing the convicted man’s life, on grounds of insanity, had it not been for the discovery of Casement’s diary. It chronicled in detail his homosexuality, which at the time was also a criminal offense. Conan Doyle’s feelings about homosexuality were more liberal than the norm, which may have been the reason why, he later was not elevated to sit in the House of Lords.

It’s risky for readers to read contemporary values into Victorian times; separation of the sexes and attitudes towards women played out differently then, in a time when gentlemen’s clubs and whalebone corsets were common, and Darwin’s theories were just beginning to challenge the Bible’s. While we may never know what Holmes’ sexuality was, or what Doyle intended, we can at least deduce Doyle was an empathetic soul.

What irks me about Downey Jr’s statements is the insinuation that because Holmes and Watson hung out together, of course, they must be lovers. Did anybody read the books? As a literary device, Watson necessarily chronicles Holmes’ adventures. But he also plays the prosaic everyman, there to emphasize Holmes’ brilliant eccentricities; much as Tom Sawyer’s domesticity highlights Huck Finn’s freedom, Nick Carraway idolizes Gatsby’s greatness, and Romeo pales to the verbal gymnastics of Mercutio. Watson worships Holmes with words, but his actions tend towards women, courting his girlfriend Mary and eventually marrying and moving away from 221 B. And though Holmes and Watson initially share the same flat, as a couple, it’s hard not to think Holmes would find something missing. Holmes might settle for Watson, but a truly passionate relationship requires a meeting of brilliant minds. To that end, Baker Street Irregulars have long pondered the possibilities of Holmes and character Irene Adler, the one woman smart enough to outwit the detective, and to capture if not his heart, his admiration.

For a film take on a queer Sherlock, try Billy Wilder’s “The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes” (1970) featuring Robert Stevens as Holmes. This made-up Holmes tale features a plot twist where Holmes claims to be gay, to get out of marrying an overly persistent Russian ballerina. But in true Wilder fashion, Holmes never really says he’s not gay. And Colin Blakely as a bumbling, skirt-chasing Dr. Watson, never quite catches the full insinuation of Holmes’ words. Stephens’ gay portrayal trumps Downey Jr’s, by incorporating Holmes’ brilliance with the wit (but also the melancholia) of a gay voice.

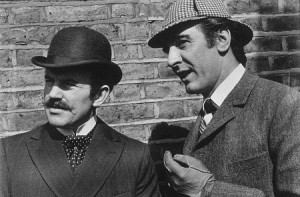

I have to say that I was also frustrated by Ritchie’s film because I’d just recently watched five episodes of the Russian “The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson” – a TV series which ran from 1979 to 1986, staring Vasily Livanov as Holmes. Holmes purists, and readers who hold Holmes dear to your hearts, these are for you. Find them, track them down, don’t miss them. It seems odd to go east to find a better Baker Street than the BBC, but trust me. The Russians’ dedication to text is noticable. Mrs. Hudson, Professor Moriarty are wonderful, and even none speakers will smile when Holmes declares, “Elementary my dear Vatson!” in Russian.

An added treat is glimpses viewers get of Russian art nouveau interiors. Gorgeous and cold, they frame the grandeur, chill, and melancholy of the stories. And the costumes! Every bit as gorgeous as Merchant Ivory productions, they also convey nuance- the discomfort of itchy tweeds, the seductive tilt of a women’s hat. And the costumes include technology of the time; Watson drives an early motorcycle (with sidecar), while Holmes struggles to adapt to his brother’s use of the new fangled telephone.

This Holmes is not gay. But Western viewers will note the body language and personal space is Russian. In the episode where Holmes purportedly dies, Watson sits down – and cries. What Brit or Yank version would include the same? Yet the camaraderie and closeness conveyed by these characters will leave viewers with tears in their eyes too.

The Russian films, like Wilder’s, capture the sense of longing of a brilliant man who never finds an equally brilliant love, and for whatever reason, is not going to even try. It’s part of the tinge of melancholy that makes Holmes so appealing. It’s why Holmes plays the violin, not the trumpet.

But finally, it’s important to recall when (and how) most of us read Sherlock Holmes — as adolescent escape. Doyle never thought of his stories as great literature. Is Holmes gay? Maybe that’s not the point. After all, Holmes and Watson live the 10-year-old’s dream existence: they’re free to run around the city solving crimes, sharing cool digs with their best friend, cared for by a woman who brings them food and cleans up after them, who’s not their mom. Even Bert and Ernie never had it so good.