A Look at Bisexuality in Science Fiction

Author: Cecilia Tan

January 18, 2015

As a young bisexual growing up in the 1980s, when I thought I was possibly the only one of my species, I was drawn to science fiction because while I didn’t see space for myself to exist in contemporary stories, I could imagine a world that included people like me only by imagining other worlds. I wasn’t the only one who felt that way: many writers also used the expansive canvas of worldbuilding and futurism that science fiction afforded them to explore sexuality “outside the box,” and bisexuality in particular is a trope that has been explored variously in every era of the genre.

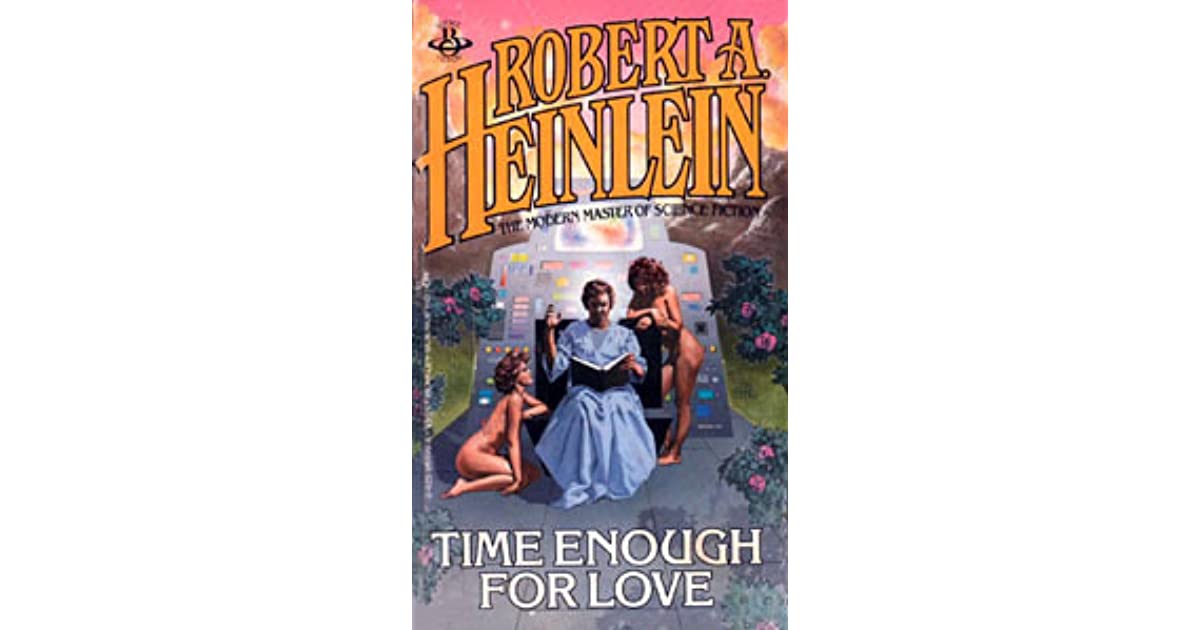

The bisexuality trope entered science fiction literature very early in the genre’s history. Robert Heinlein introduced his recurring character Lazarus Long in a 1941 issue of the pulp magazine Astounding Stories, though some would say Long’s “coming out” as a bi character didn’t really take place until 1973, with the publication of the novel Time Enough for Love. By that time a number of other infamous bisexuals had appeared in science fiction: the murderous pedophile villain Baron Harkonnen in Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965), Barbarella (1968 film), and Philip Jose Farmer’s “Lord Grandrith” (a thinly-veiled Tarzan) and “Doc Caliban” (Doc Savage), who get it on in Fest Unknown (1969).

Lazarus Long went bi at the same moment in popular culture when bisexuality was equated with avant garde–perhaps futuristic–social attitudes. Bisexuality as an identity or orientation existed so far outside the monosexual “norm” that David Bowie’s public image was cemented as not only bisexual, but alien from outer space. (Bowie would much later explain in interviews that he latched onto bisexual identity as a way to shock the mainstream and give himself street cred, but despite a well-documented dalliance with Mick Jagger, he eventually settled into lifelong heterosexuality.) Science fiction literature of the 1970s used bisexuality as a signifier of outsider/other, alien, or futuristic status. Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren (1975) uses the sexuality of “The Kid” as well as many other narrative elements to dislocate the reader from the status quo. Many of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s characters in her Darkover books are bisexual, in particfular the Darkovans (as opposed to the Terrans from Earth, who are more “like us.”) Joanna Russ’s The Female Man was written in 1970 but published in 1975 and intertwines elements of bisexuality with deep thinking about gender and gender roles. Another thinky example from the time is David Gerrold’s The Man Who Folded Himself (1973), where the homoerotic aspects enter with the idea that time travelers can have sex with themselves. Even the not-so-thinky but just as subversive Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) runs in this gestalt track of bisexual-as-other.

By the 1980s, though, the free-love sixties and the swingin’ seventies were over, Reaganomics was the order of the day, and while various science fiction and fantasy writers continued to explore bisexuality, the culture wars of the period meant that in some cases the sexuality was highlighted, in others downplayed. On the highlight side we had David Bowie and Catherine Deneuve as bisexual vampires in the film adaptation of Whitley Streiber’s The Hunger (1983). Marion Zimmer Bradley’s breakthrough mainstream bestseller The Mists of Avalon (1984) featured a bisexual Lancelot caught between his love for Guinevere and his lust for Arthur. At the other extreme, you have examples like Jack L. Chalker’s Four Lords of the Diamond (1981, a body-swapping novel) and George R.R. Martin’s 1980 novel Nightflyers, which featured a bisexual female main character, but when adapted for film she was straight-washed.

Some authors carried the social experiment ideas of the seventies forward, positing societal structures that embodied inherent bisexuality, where bisexual-as-other moved from individual status to groups. Heinlein continued to write novels with many bi characters (Friday, Andrew-who-becomes-Libby Jackson, Ira Weatheral, and many more) and explored ideas like line marriages. Diane Duane’s Door Into Fire (1979) and Door Into Shadow (1984) presented a culture where group marriages was the norm. And in 1987 Iain Banks began publishing the Culture novels, all of which feature an advanced future in which characters can change gender merely by thinking about it.

Coming into the 1990s, sf literature saw “the bi trope” dwindle while genuine representations of gay and lesbian characters began to finally appear, with a few bisexuals thrown in. Some authors, notably Tanya Huff (The Fire’s Stone, 1990), Fiona Patton (The Stone Prince, 1997), and Melissa Scott (Shadow Man, 1995) included bi characters and represented their bisexuality as something normal within their universe’s context. But in the 1990s we also saw a fair amount of what might be deemed push-back against “dated” concepts of bisexuality and encroaching possibilities of queerness. In a much-reviled 1991 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Dr. Crusher falls in love with a symbiotic alien, but to save his life he transfers from a male to a female body. So much for love: Crusher can’t deal with him being embodied as female and ends the relationship. John Varley’s Steel Beach (1993) has gender swapping as a norm, yet the relationships depicted are heterosexual. Varley does make a very interesting distinction between how attraction would work if you could change gender: what would you call a person who was always attracted to a specific sex regardless of their own sex, versus one that was always attracted to the same or opposite sex? But the actual relationships on the page in Varley’s works are largely straight. The go-to trope of bisexuality was on the wane.

This waning was not necessarily bad, as various authors and creators were making attempts at representation across many types of orientation, representing true life experiences for their characters rather than relying on grand gesture world-building concepts to inject bisexuality-as-otherness. By the turn of the millennium we start to see various notable bisexual characters: Phedre in Jacqueline Carey’s Kushiel’s Dart (2001), Claudette and Pamela in Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse books (launched in 2001), Inara from the television show Firefly (2002), and let’s not forget Willow’s bisexual arc in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (2000). The list continues, Elizabeth Bear’s Jenny Casey (Hammered, 2004), Grace Choi in the DC Comics title The Outsiders (2003), and how about Caprica Six in the 2004 television reboot of Battlerstar Galactica. There’s one other thing notable about all these examples from 2000-2006: they are all female. Where did all the male bisexuals go?

I’m happy to report that the men have had a few high profile comebacks since. None was more visible than Captain Jack Harkness of the Torchwood television series (launched 2006), followed in 2008 by Erik Northmen in the True Blood television adaptation of Charlaine Harris’s books. But the television world continues to have its push-backs, as with the vehement–sometimes nastily homophobic–denials by actors and writers regarding a bromance between the angel Castiel and Dean Winchester on the show Supernatural. In the realm of the written word, award-winning British science fiction writer China Mieville has male bisexuals in various books. N.K. (Nora) Jemisin’s much-lauded Hundred Thousand Kingdoms series (2010) features multiple characters who are casually bisexual to the point it’s not mentioned as unusual. We continue to see issues of gender and bisexuality touched on in the works of longtime writers such as Jo Walton, Ellen Kushner and Delia Sherman. Interestingly enough, now most of the male bisexuals beginning to appear are being written by female writers, especially those entering the field from the vectors of fanfiction (where the practice of queering canonically straight male characters is common) and romance. J.R. Ward’s mega-bestselling Black Dagger Brotherhood series features an ongoing saga of vampire war with a new romantic heterosexual pairing in each book. In 2013 a previously established character, Qhuinn, finally took the spotlight with his male partner Blay in Lover at Last. Rie Warren’s futuristic military Don’t Tell series also mixes male-female pairings with male-male pairings.

These works are still the exception. The audience for strictly gay “male-male” romance and erotica is much larger than that for bisexual male or female romantic leads, but I’m heartened that there is a corner of the romance world where bisexual characters can flourish, under the banner that true love knows no gender. My own new adult romance series, Magic University, features a bisexual hero as he makes his way through four years of college. (Like many young men arriving at school, Kyle starts out somewhat heteronormative. Let’s just say it doesn’t last.) Within the framework of romance and building on the pre-existing tropes of fantasy and the paranormal that lend themselves to sexual exploration outside the gender binary, the Magic University books don’t merely make a nod to bisexuality, Kyle’s bi nature is crucial to the plot and to saving the human race. Popular male/male romance writer L.A. Witt strays into bi territory occasionally, too, with fantastic results, as in the award-winning gender-change novel Static. Elizabeth Schechter’s steampunk romance House of Sable Locks was multiply nominated for many awards and features the rare bisexual hero paired with a female heroine. These kinds of variations from the “norm” are exciting. Romance has a reputation as a hide-bound, restrictive genre, while science fiction’s reputation is the opposite; rule-breaking and upsetting the status quo are supposedly in the genre’s DNA. But perhaps like bisexuality itself, a kind of hybrid vigor results of a mix of the two. I plan to keep my eye on paranormal and futuristic queer romances in the hopes that a new hotbed of bisexual representation is about to flourish.