‘#girlgaze: How Girls See the World’ by Amanda de Cadenet

Author: Sarah Fonseca

December 3, 2017

In 1981, Gay Block, a thirtysomething mother, newly divorced and out (as both an artist/photographer and a lesbian), set out for Pinecliff, an all-girl’s summer camp nestled away in rural Maine. Block had spent her own youth’s balmy summers hiking and rowing there. This tradition, continued by her daughter, would be rendered eternal by her camera.

Camp Pinecliff, 1981, the series of unposed black and white portraits Block took that summer, were some of the first photographs to capture the last dregs of girlhood, mid-dissipation. She shot with one unintimidating rule: no smiling. This one second of seriousness in such a playful space gave way to stunning, telling images. One girl, slumped so deeply into her bunk that she seems like a part of it, clutches a lollipop with one hand while the other guards her prized letters from home; another fearlessly holds a recoiled snake. The campers’ clothing, trapped in the era of tube socks and Nike Cortez sneakers, has its limits tested in ways that an adolescent girl can overwhelm fabric: through stretching her t-shirt over her knees after a swim; by nervously stuffing her arms down into overall shorts until her hands poke from under the hemlines; through pubescent tedium. “They were beautiful, full of promise on their faces, and I could see their future, in a way. I could almost see the faces of the mothers they were going to become,” Block reminisced a few decades later.

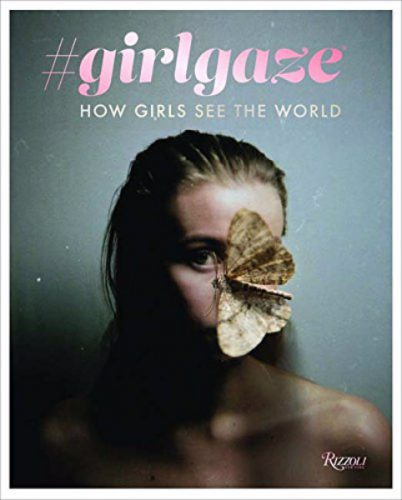

Today, Camp Pinecliffe, 1981, illustrates how circumstances native to women–one’s own girlhood, motherhood, divorcéehood, lesbianism–can bolster creative vision, encourage stamina, and even negotiate access to unseen realms. Yet these same circumstances remain unusual among photographers; ask someone to thumb off women who shoot and you’re likely to receive a white marble cemetery: Arbus, Abbott, Lange, Maier, Woodman. Maybe a Leibowitz or Sherman, if you’re lucky. In response to this dearth of working female photographers, photographer and media entrepreneur Amanda de Cadenet and her team have curated #girlgaze: How Girls See the World, a Rolodex of the best young female photographers that conveniently masquerades as a linen coffee table book. Each featured photograph includes the name and age of its photographer, as well as their Instagram handle. #girlgaze is a tacit reminder that one has no excuses for not knowing any women worth employing; there are literally hundreds of portfolios a few clicks away. As de Cadenet writes in the #girlgaze manifesto:

| girl |

Taking back the word girl, we are pushing back against the cultural projections and traditional gender roles imposed upon girls from the outside world, media and culture. Instead, we aim to represent the intelligence, creativity, complexity and diversity of girls’ experience–across nation, ethnicity, race, religion, sexual orientation, economic background. It is up to those who identify with being a girl to break the boundaries and determine their own identity, sexuality, and beauty.

| gaze |

We are telling stories and creating images by taking the camera (or any medium) into our hands to express our viewpoints, reflect our states of mind, share our interests–whether in politics, fashion, tech, beauty, business–and to show the world how we see it.

De Cadenet’s book is in good company. In recent years, the number of women who aim to write away the gender gap has grown, many cheekily borrowing project names from Laura Mulvey’s fraught male gaze theory. Daniella Shreir’s feminist film journal Another Gaze, British-Sri Lankan author Charlotte Jansen’s Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze, and Lissa Rivera’s NSFW: Female Gaze catalog for New York City’s Museum of Sex all assess the current feminist creative landscape while nudging for a reappraisal of artistic canons. #girlgaze, however, starts ’em young.

The photos that fill nearly all of #girlgaze’s 272 pages were selected from over 750,000 images that were submitted via Instagram using the project’s eponymous hashtag and then organized into broad categories: Family, Relationships, Lovers, Friends, Political Movements, Marginalized Communities, Technology, Culture, This is Me, Mental Illness, Suicide Survivors, Depression, and Grief (the sixth of which could’ve stood a bit more contemplation). The oldest featured photographer is in her late forties; the youngest, still too tenderly-aged to drive herself to school. Publication is breeding ground for confidence; devotion permits “hobby” to become “art.” But so do ink, glossy stock, and the perfect-bound cover. #girlgaze’s greatest feat is that it allows its girls, regardless of age, to experience creative “arrival” in the way that Girl Scouts has allowed them arrival in their paddling skills, or Academic Decathlon in their ability to multiply decimals. #girlgaze also includes generous letters of encouragement to girls from industry pros like Lynsey Addario and Inez van Lamsweerde that double-down on the boost of confidence that publication alone offers.

The photos that fill nearly all of #girlgaze’s 272 pages were selected from over 750,000 images that were submitted via Instagram using the project’s eponymous hashtag and then organized into broad categories: Family, Relationships, Lovers, Friends, Political Movements, Marginalized Communities, Technology, Culture, This is Me, Mental Illness, Suicide Survivors, Depression, and Grief (the sixth of which could’ve stood a bit more contemplation). The oldest featured photographer is in her late forties; the youngest, still too tenderly-aged to drive herself to school. Publication is breeding ground for confidence; devotion permits “hobby” to become “art.” But so do ink, glossy stock, and the perfect-bound cover. #girlgaze’s greatest feat is that it allows its girls, regardless of age, to experience creative “arrival” in the way that Girl Scouts has allowed them arrival in their paddling skills, or Academic Decathlon in their ability to multiply decimals. #girlgaze also includes generous letters of encouragement to girls from industry pros like Lynsey Addario and Inez van Lamsweerde that double-down on the boost of confidence that publication alone offers.

Hunger makes Carrie Brownstein a modern girl, but what about the rest of us? For Jessica Fulford-Dobson, aged 47 of London, a skater girl from Kabul with too-big pink boarding kicks and an iridescent blue shayla tucked beneath her helmet makes her a modern girl. For China Leona Moore, aged 25 of Detroit, eight carefree black girls in their smoky brick-and-mortar boudoir, one of whom eyes a Complex Magazine pin-up appreciatively, make her a modern girl. For Luisa Dorr, aged 27 of Brazil, it’s two girls, one just above toddler-aged and the other approaching adolescence, wearing identical dresses, that makes her a modern girl. For Remi Riordan, aged 19 of New Jersey, two long-haired blonde girls making out with their eyes closed makes her a modern girl.

The modern girl-photographer has a range of skills: she can shoot candids, build colleges, narrate photographic fairytales, and document through photojournalism. Her gaze can be humane or err towards the colonial. She is still figuring her shit out. She can be unapologetically queer. She really, really appreciates millennial pink. She also digs the reappropriation of items and people from her own childhood as props: lollipops, big bubblegum bubbles, the annoying little brother, the reimagined first crush. The modern girl isn’t naïve. She’s Robin de Puy, photographing a nude woman whose infant, slung to her hip, strains to reach her breast as the mother stares blankly into the camera; she’s Amanda Stidam, photographing suicide survivors and helping them tell their stories autonomously. Most importantly: she’s deeply committed.

A quarter century after Camp Pinecliff, 1981, Block and her camera revisited her girls in the series 2006: The Women the Girls Are Now. Many of her subjects had birthed camp-goers of their own, some of which appear in alongside their mothers. The women gaze into the lens with expressions uncannily similar to those from all those years before; as though they’ve always understood how the world works.

#girlgaze: How Girls See the World

By Amanda de Cadenet

Rizzoli

Hardcover, 9780847860890, 272 pp.

October 2017