Remembering the Work of Stan Leventhal

Author: Christopher Bram

April 12, 2020

The following is the new introduction for the 2020 edition of Stan Leventhal’s Mountain Climbing in Sheridan Square (Requeered Tales)

I first met Stan Leventhal in 1988 when Joel Redon invited me, Stan, and Patrick Merla to a friend’s apartment for dinner. It was a gay writers night—Patrick had published us at the New York Native. I knew Stan wrote fiction and edited skin magazines. I was nervous about meeting him. For some reason–I don’t know why–I assumed he would be super macho and butcher-than-thou, with a chip on his shoulder the size of a cinder block. I’ve never been so wrong about anyone in my life. Oh, he was somewhat guarded at first, studying me with a raised chin, lowered eyelids, and elongated upper lip–Stan’s patented who-are-you-? look. But then I said something that gained his trust, probably a silly joke, and he promptly relaxed, becoming the animated, head-bobbing, hand-wagging talker all of his friends knew.

We didn’t consciously initiate a friendship. It just happened. We became better acquainted when we were on the steering committee of the Publishing Triangle, an association of lesbian and gay men in the book business, and tended bar together at their parties with Stan’s buddy, Michele Karlsberg. Later, as if needing monthly fixes of each other’s company, we began to meet for dinner, usually at Woody’s, a burger-and-salad restaurant in Greenwich Village halfway between his apartment and mine. My partner Draper sometimes joined us, but usually it was just me and Stan. He was almost always there when I arrived, with a glass of Jack Daniels by his elbow and a feline grin full of literary news.

Right from the start our friendship was about books, the reading, writing, and love of them. Roz Parr once called Stan an enthusiast, which is the perfect word for him. Consuming as many as three books a week, he seized me as a fellow addict with whom he could share the good news. We talked about people, too, but usually in the context of books. I first heard about Bob Locke, the ex-lover who remained his best friend, as simply the man who had turned him on to Elizabethan history. (Mountain Climbing in Sheridan Square is dedicated to Bob.)

Stan was nothing if not eclectic in his reading. Among the books and authors he loved were: Jean Genet, Anne Tyler, Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All by Allan Gurganus, Samuel Delany, Daniel Deronda by George Eliot, Don DeLillo, Mary Gordon, Guy Davenport, and Allen Ginsberg. When Stan found a writer he liked, he insisted on reading everything they’d written, working methodically through their titles like slices in a loaf of bread. There was no predicting who or what would seize his interest. He loved science fiction, historical fiction, Victorian fiction, and mysteries. He did not read trash, however, and liked to quote John Leonard’s remark that there are well-crafted books in every genre and such books are not trash.

Reading was his religion and Stan was a born proselytizer, which led to his role in founding the library at the Lesbian and Gay Community Center. He once confessed to me that his real reason for joining the Publishing Triangle was to use them to launch a gay and lesbian library. He succeeded beyond his own expectations. The Pat Parker/Vito Russo Memorial Library became a permanent reading room with a collection of over 10,000 volumes. (I am sorry to say the Center discontinued it a few years ago, claiming gay people no longer needed their own library.)

Another enthusiasm Stan shared with me, and with Draper, too, was his love of music. Again, he was remarkably eclectic. He loved everything: rock, country, classical, and jazz. The breadth of his knowledge was amazing, with a few quirks, such as his indifference to most opera and a disdain for Mozart that I still find puzzling. Draper often pumped him for information about early country music. Stan introduced us to the Bristol Sessions of 1927, when Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family made their first recordings. He tried to convert us to Kitty Wells, one of Patsy Cline’s heroes, but her backwoods twang was just too harsh for our ears.

However, Stan was the easiest person in the world to disagree with. There was no egotistical need to prove he was right and you were wrong. This extended to discussions of his own writing. Twice he showed me works in progress and quietly listened over coffee while I pointed out what was good and what I thought needed work. He accepted my criticisms gratefully, said I’d been very helpful, thanked me profusely for taking his fiction seriously, then left the manuscripts exactly as they were.

My favorites of his books remain his two autobiographical novels, Mountain Climbing in Sheridan Square [1988], and Skydiving on Christopher Street [1995], chiefly because there is so much of Stan in them. But his love of fiction in all genres led him to experiment with other types of stories. “I like to fuck with genre,” he once told me. He put his own spin on mysteries, fantasy, comedy, and science fiction.

In a vocation full of overblown egos—and ego is a tool of the writer’s trade—Stan kept his turned down low. It was certainly there, but without righteousness or venom. He read gay and lesbian peers without being blinded by competitiveness or resentment. He was not uncritical. Several writers are now inadvertently blessed in my memory because Stan once nailed them with a gently damning phrase, rolling his eyes as he said it. “Oh, it’s the same old Dennis Cooper novel,” he sighed. “A man sniffs a boy’s asshole and then kills him.” He did not bear grudges, knew how to hate sins and forgive sinners (with the exception of the weasels who stole control of Amethyst, the small press he founded with Michele Karlsberg). He was one of the few people with whom I could dish other writers and walk away without feeling dirty.

Stan was editor-in-chief at Mavety Media Group, publishers of Torso, Inches, and other men’s magazines. At one point, when I needed money and Stan needed an assistant editor, he hired me for three months. There were three assistant editors who copy-edited the erotic fiction and occasional non-erotic essay; the photographers and models worked elsewhere. The job was about as sexy as a gig at Popular Mechanics. You don’t really know someone until you work with them and I was afraid I’d discover the Mr. Hyde side of Stan’s good Dr. Jekyll. But no, he was the same careful, considerate man at the workplace. Overworked and often preoccupied, he still took time to drop by our cubicles and talk about books or music. Those arts really were lifelines for Stan.

A gentle, self-effacing man—maybe too self-effacing at times—he could be cussedly independent. He was reluctant to ask for favors and unsure what to do with them when they were given. When he became sick with AIDS-related thrush and later pneumonia, he never let me help him up the stairs of his four-floor walk-up or even pick up his groceries. However, he did request friends to bring him books when he went into the hospital for the first time in the summer of 1994. That same year, the day after Christmas, he telephoned and asked me to go with him to the hospital. But he didn’t need help, he wanted company, the presence of a familiar face and ear when he reentered a world of doctors and respirators. He died three weeks later.

I want to remember pain as well as pleasure, but a hospital is too impersonal to provide the final image here. Instead, let me describe the night a few months earlier when Stan invited me and Draper back to his apartment to listen to a demo tape he made in the early 1980s, when he was not yet a novelist or magazine editor, but a songwriter and musician, a Jewish boy from Long Island who played with a country-western band. He was touched that we wanted to hear his songs; he hadn’t played the tape in years. He undressed when we got to his overheated apartment —Stan was not shy about lounging at home in his underwear with friends—put on the tape and sat very still in a straight-back chair, his long hands folded over his bare legs, listening intently to an exuberant, high lonesome voice from fifteen years earlier. After we left, Draper said he looked just like a Picasso of the Blue Period.

As I wrote earlier, Mountain Climbing in Sheridan Square and its sequel, Skydiving on Christopher Street, are my two favorite books by Stan. I recently reread Mountain Climbing, hesitant at first, afraid it would hurt to remember a lost friend or, worse, that the novel wouldn’t hold up. But it’s a wonderful book that has improved with age. Yes, Stan is here, in all his natural, easygoing humanity. It was good to see him again. But I found so much else as well. There is New York City in the 1970s and 1980s, before money and gentrification changed it beyond recognition. There are the younger days of myself and my friends, when the world was still new and the future lay ahead of us. There is a matter-of-fact realism full of sanity and wisdom. And the novel is beautifully executed, the prose as clear and natural as water, without sensationalism or false sentiment.

The unnamed narrator is undeniably Stan, as the apartment overlooking Sheridan Square is undeniably Stan’s apartment. The book is artfully artless, like entries in a daybook, episodes from the present mixed with episodes from the past. We move back and forth over a single decade in New York, with occasional visits to Long Island where the narrator grew up and Boston where he went to college. We meet two different lovers, a good one and a bad one, and many friends. This mixed salad of time creates a collage of anecdotes and verbal snapshots that feels more like real life than fiction.

The novel does not take place in a gay ghetto, but in the more porous, bohemian world of the arts. Friends include a painter, an actress, singers and musicians. The narrator performs in an ethnically diverse country-western band called High in the Saddle. The mix of men and woman feels perfectly natural, as does the racial mix. There are straight men, some who come off well and others badly. There are even children, with several bouts of babysitting. The creative life draws everyone together at a time when the city was still affordable for artists. The narrator supports himself with a wide variety of part-time jobs, including work in a record store, a theatrical ticket office, and on an assembly line in an electronics factory downtown—another piece of New York that has disappeared. Life in the arts provides the metaphor behind the novel’s title. Being any kind of artist is like climbing a mountain. You can’t see where you’ve been when you look down and you can only imagine what’s up ahead. And when you get there, then what? There’s just the view. The thrill is all in the climbing.

The narrator, who loves science fiction as much as Stan did, occasionally imagines a figure called simply the Alien, an extraterrestrial visitor who coolly watches life on earth, seeing things as they really are, without concern for such trivia as gender, race, money, or death. He is the book’s voice of reason, its distancing device, its coping mechanism.

The coming of AIDS is the great painful event in these pages. It doesn’t dominate the novel, but is folded into daily life with jobs, art, love, and friendship. It’s not the all-consuming catastrophe now imagined in fiction and plays written by people who weren’t there, but a slow fire that takes away friends and neighbors, one by one, while the rest of life goes on. Stan continued to write about the plague with the same realism in the sequel, Skydiving on Christopher Street, adding politics and activism to the mix. Finally, of course, that slow fire would consume him. (It consumed Joel Redon and Bob Locke as well.)

But in the world of the novel, the scrambled time salad of this book, life goes on. As it went on for the rest of us, without Stan. Yet in the disguise of his nameless narrator, Stan is still alive in the present of these pages—I use “present” in both meanings of the word. I was overjoyed to spend time with him again. I am now delighted to introduce him to you.

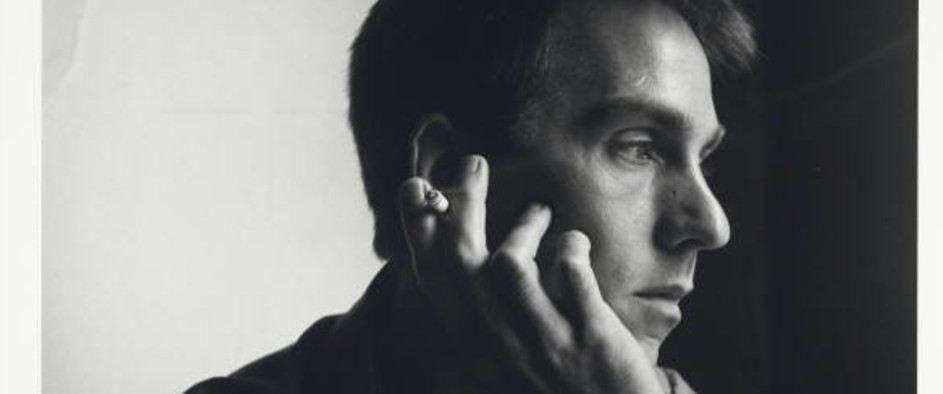

Photo by Robert Giard. Copyright Estate of Robert Giard.