Retracing My Black Queer Literary Roots

Author: Marrion Johnson

March 29, 2020

The summer before I began my MFA program in Creative Writing at Saint Mary’s College, I found myself anxiously perusing the aisles of a boutique bookstore in San Francisco, desperate for a little bit of creative inspiration.

It had been weeks since I’d written anything useful, which of course only fueled my anxiety and feelings of self-worth. I knew I could write, but I struggled with finding my voice and feeling capable of completing work that I felt proud of. And because of these rising tensions, the simple thought of entering graduate school was, quite frankly, stressing me out. Determined to practice a little patience and kindness with myself, I decided to go book hunting in the city with a friend, in an effort to take my mind off of my worries, if only for a little while.

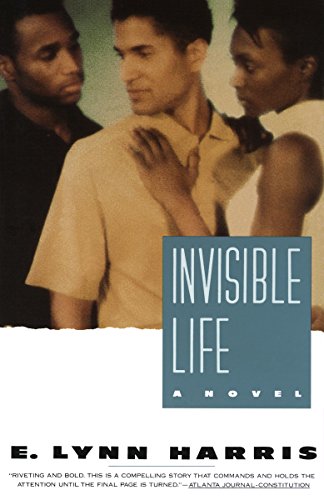

“Have you ever heard of E. Lynn Harris?” My friend asked, holding out a used copy of Harris’ first novel, Invisible Life. The book’s cover was a photograph of a handsome brown-skinned man in what appeared to be a love triangle with a Black man and woman to his left and right sides. Needless to say, I was captivated by the cover and my interest suddenly piqued.

I glanced at the book and replied to her question with an innocent shrug. The name was familiar but I couldn’t put a face to it. Since we were in the Castro, San Francisco’s gay district, I figured Harris had to be queer. And from the look of the cover, I was certain he was Black. So, I picked up a copy and instantly started skimming through its pages.

“You must read this novel,” my friend implored before ushering me to the counter to make sure I purchased the book that she said, and I quote, “turned me out” as a teenager. I didn’t put up much of a fight. Losing myself in the stories of other writers’ work, I figured, might be just what I needed to overcome my writing slump and jumpstart my creative flow.

I placed the paperback into my backpack where it remained for several weeks until I finally cracked it open later that September.

Indulging in an Invisible Life

Born in Flint, Michigan in 1955, E. Lynn Harris grew up traversing the south, living in Texas, Georgia, and Arkansas. He worked as a computer salesman in the 1980s but decided to commit himself to his writing due to the encouragement of a friend dying from AIDS, and after his own failed drunken suicide attempt in 1990. By the following year, in 1991, he had completed and self-published his first book, Invisible Life, which he sold from the trunk of his car for years before eventually catching the eye of a national publisher and rereleasing the novel to great acclaim in 1994.

The more I learned about Harris, the more excited I became to dig into his book. A big part of my writing practice has been to prioritize reading as a source of inspiration. I read to see how others who came before me wrapped their heads around the stories that sometimes felt insurmountable before they finally found the courage to bring their tales to the page.

I’d already been obsessively reading the works of many talented Black fiction writers like Toni Morrison, Octavia Butler, and Tananarive Due, to name a few. But I had yet to come across what I felt to be the true canon of Black queer fiction. I mean, I knew that it was there. Many of us know, love and revere our collective literary father James Baldwin. And of course, I’m familiar with his work, namely his first two novels Go Tell It On The Mountain and Giovanni’s Room. One was explicitly Black, another was explicitly queer. But the two hadn’t converged. And honestly, although I had begun to see more Black queer characters on the big and small screens, I still had yet to come across an intimate portrayal of them, of us, in the literature that I loved so much. So, finally having my hands on the work of an author like E. Lynn Harris–who for all intents and purposes, was just like me–was thrilling, and once I actually resigned myself to reading his book, I immediately began to breeze through the pages.

Invisible Life follows Raymond “Ray” Winston Tyler, Jr, a rising southern-born attorney, who comes to explore his bisexuality in college after an intense romance with a younger athlete, and who eventually embraces the bi “lifestyle” while living in New York City. It is in New York where Ray learns all about the city’s thriving Black gay community, often bar-hopping with his friends Kyle, an out Black man, and JJ, their supportive straight woman friend, and engaging in romantic dalliances of his own with a series of men who are more often than not, closeted. There’s just one thing: while Ray is slowly coming to terms with his own budding sexuality, he is not out at work or with his family back home in Alabama, and still craves the normalcy that comes with hetero life. Eventually, Ray even finds himself in a love triangle with a fellow closeted man, Quinn, and a rising Broadway starlet, Nicole. Throughout the novel, Ray goes back and forth between choosing his undeniable chemistry with Quinn, who happens to be married, or settling down with Nicole and following the script that has already been written for him by his family and society.

What I appreciated most about Invisible Life was E. Lynn’s commitment to humanizing the closeted, or “down low” (aka DL) experience. For as long as I can remember, the term down low has been met with a serious amount of hostility from straight women who fear of learning that their partner is secretly sleeping with men, and openly gay men, like myself, who’ve become frustrated with the constant narrative of deceitful, undercover gays taking equal advantage of the men and women alike.

I’ll be the first to admit that as a young person, I too looked down on DL or closeted men. After coming out before my freshman year of college in 2007, I relished in the freedom that came from simply being who I was, wearing what I wanted, walking with an extra strut in my step, expressing myself as I pleased. Sure, I’d endured homophobic microaggressions from straight men who thought I was too flashy to join their fraternities or too femme to lead their student groups. But, living in my truth drew me to the people that were genuinely there for me. The ones who lifted me up and encouraged me to chase the stars, not despite my sexual orientation, but because of it.

Still, it wasn’t until I fully immersed myself in the pages of Invisible Life, did I begin to remember the serious internal struggle that came with attempting to live a life in your truth, whatever it may be. I recalled the mental hurdles it took to address the internalized homophobia that constantly tells us to distance ourselves from other queer folk. We see this on the page when Ray doesn’t stand up for a gay applicant at his law firm, afraid that doing so might out him. “I didn’t know him, but I couldn’t risk the chance of being found out by being supportive.” I remembered the hateful things some of us would say to ourselves and the ones we love in order to fit in enough to be accepted. We see this as well when Ray combats his flamboyant best friend for using effeminate gay lingo. “Kyle, I’ve told you about that ‘Miss Thing’ shit. We have a deal. Don’t ever call me that again, Kyle. I just don’t play that shit.” And how could I forget about the constant need to prove our masculinity in a society that refuses to embrace a diversity of manhood? We see this when Ray finally opens up to his father about his sexuality. “Pops, no matter what you think of me, I’m no sissy. I am the man you raised me to be.”

It was difficult hearing Ray say hurtful things to other queers, especially to his best friend who, unlike Ray, faced scrutiny from gay and straight people alike for simply being who he was. Equally troubling was seeing Ray so easily dismiss the femme gay experience all so that he can still be seen as a “man” by a father who likely never even questioned the patriarchal framework society enforced onto him and simply molded himself into the idea of what a “man” should be.

As challenging as it was witnessing Ray’s struggle to accept himself, I found it refreshing to see such honesty on the page. As a fiction writer, I can admit to the occasional fear that comes with presenting nuanced and complex characters, particularly Black ones who are less than perfect and might have opinions that go against everything that I personally believe and value. However, Harris reminds me of the importance of illustrating the humanity in those folks; in the people who are still learning who they are and how they might go about showing up in the world. After finishing Invisible Life, I not only found myself expressing more empathy for the closeted folks in my community, but I also felt a deep appreciation to E. Lynn Harris for reminding me that everyone, even those who I might not understand, has a story that deserves to be told.

Believing in those B-Boy Blues

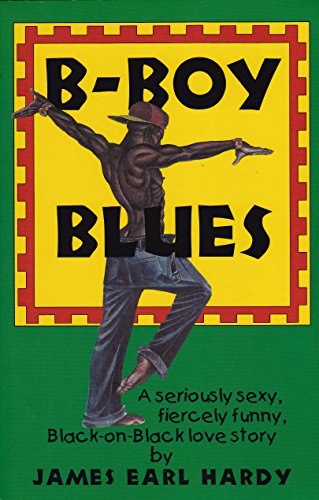

Eventually, I began telling everyone I knew about Invisible Life and asking if they’d ever heard of E. Lynn Harris. When I mentioned my latest obsession to my editor at Lambda Literary, a Black queer man who also experienced the New York scene of the 80s and 90s, he shared that in addition to Invisible Life, what I really needed to read was B-Boy Blues, by James Earl Hardy. B-Boy Blues, he felt, offered a more authentic depiction of the era that many of us youngsters perceive through a skewed lens. A world that wasn’t wrapped up with the internal tension of coming out and that instead was rooted in love and possibility, while simultaneously offering a glimpse into the lives of both professional and working-class Black gay men.

Eager to examine more work from the Black queer elders who came before me, I jumped at the opportunity to dig into Hardy’s background and to read his book as well. Hardy was born in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn in 1966, and pursued a career in journalism after completing his schooling at St. John’s and Columbia University. Just like Harris, Hardy also published his first novel, B-Boy Blues, in 1994, during a time when the AIDS crisis was at an all-time high and when straight America had finally begun to recognize the tragedy that had plagued our community for over a decade.

But, what I appreciated so much about B-Boy Blues was that despite the troubling times in which it existed, the story focuses purely on love, friendship, and self-acceptance. In B-Boy Blues, we meet Mitchell “Mitch” Crawford, a young journalist living in Brooklyn who is very eager to fall in love. Unlike Invisible Life’s Ray, Mitch is out and proud, and surrounds himself with other out and professional Black gay men, most notably his trio of friends, Gene, B.D. and Babyface. Mitch quickly and unexpectedly falls in love with Raheim, a 21-year-old B-Boy (translation: fuckboy lite), who turns him out in the bedroom (!), and gives him his first real taste of true love. Throughout the story, we follow the ups and downs of Mitch’s relationship with Raheim (aka Pooquie), who is a closeted, young father, and believes in maintaining heteronormative roles even in romantic relationships with men. And in the end, Mitch’s struggles with Raheim lead him to question if and how he might show up as his full self, and embrace his masculinity as well as his femininity in his love and personal life.

Flipping through the pages of B-Boy Blues, I noticed myself feeling something that I hadn’t felt during my reading of Invisible Life. Whereas E. Lynn Harris was successful in helping me to empathize with the closeted Black gay experience, in James Earl Hardy’s work, I felt as if I had been seen fully and completely for the first time on the page. The story’s main character, Mitch, reminded me so much of myself. He too worked amongst hypocritical white liberals who often refused to recognize the very real impact of institutionalized racism on the Black body. Mitch also was unapologetically outspoken about his beliefs, and ready to put anyone in check for their homophobic stances at the drop of a hat, even his family. We see this when he confronts his stepfather, Anderson, who suggests that white gays are co-opting Black folks’ civil rights movement. “Whose movement, Anderson? Weren’t Black lesbians and gays hosed down? Chased and bitten by dogs? Clubbed by police? Denied the right to vote? Aren’t we also, to this day, denied the right to be?”

Here, Mitch makes a crucial case that reoccurs over and over throughout the page: that Black queers deserve the right to be who we are as we are, fully and with no exceptions. We see this again when Mitch confronts his boyfriend, Raheim, for cheating on him. When Raheim dismisses Mitch’s concerns using the term “faggot,” a word that Mitch despises, he doesn’t hesitate to let his man know how he feels. “We have shared a bed for the last two months, Raheim. If he is a faggot, what does that make me and you?”

Without giving too much away, it is Mitch’s friends who ultimately help him to see how he is hiding who he really is in order to fit into the parameters of a heteronormative queer relationship. This is evident when his friend B.D. says “Mitch, you are a very special man. You have so much to offer. If Pooquie is smart, he’ll come back to you. […] He’ll have to stop being a boy and you can’t be afraid of being a man.”

In the end, Mitch has no choice but to confront the internalized homophobia that even he still exudes. Sure, he is proud of who he has become and aims to help other Black gay men feel similarly in their own lives. And still, once in the relationship that he so desperately desired, Mitch finds himself temporarily conforming to a way of living that is antithetical to his internal belief system, before finally remembering who he is and recommitting himself to his personal values.

It is through this powerful message of self-acceptance, that Hardy makes room for his character to blossom into the fearless queer that he aims to be. But he doesn’t do it on his own. Mitch, just like everyone else, requires the love and support of the ones he calls family, and it is through their help that he finds himself capable of realizing his full self.

A Black Queer Takeaway for Future Generations

After completing both of these effortlessly engaging tales of Black queerness in time when it was even more likely for a gay person to be shunned from mainstream society for simply being who they were, I couldn’t help but admire the fearlessness in the writing of these two pioneering authors. They told hard, complicated stories that not many people were open to 25 years ago, let alone today. And they didn’t have many mainstream Black queer role models or templates to look towards as they engaged in writing about those who lived and continue to live on the margins of American society. And still, they were committed to breaking down barriers and writing what they knew to be true and what they knew their communities deserved.

When I reflect on the feelings of inadequacy and doubt that I engaged in less than a year ago as I embarked on a new chapter in my own writing journey, I feel overwhelmed with a sense of gratitude and possibility. Even though writing is hard, and sometimes words fail to find us in the moments that we so desperately crave them to, I’m reminded of the power of lineage and the importance of looking towards those who came before me for hope and inspiration. I’ve read the work of so many incredible Black authors, but I can say without a shadow of a doubt that in these two novels I have felt seen, held, and heard, like no other. And that’s something that I not only want to pass on to future writers like myself, but something that I now know I have deep within me. Why? Because the elders did it first. And if they could, then I know I can too.