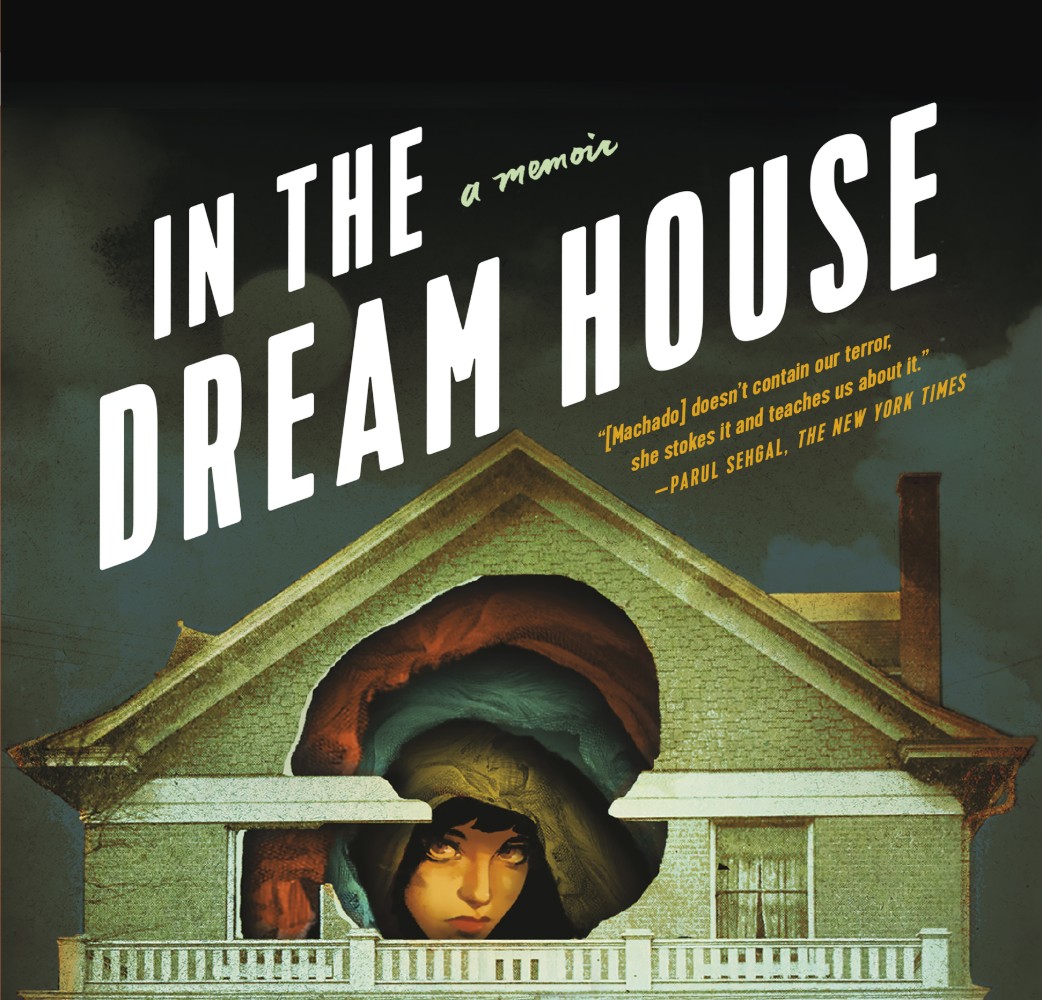

‘In the Dream House’ by Carmen Maria Machado

Author: Alyssa C. Greene

November 3, 2019

“Places are never just places in a piece of writing,” writes Carmen Maria Machado. “Setting is not inert. It is activated by point of view.” Her new memoir, In the Dream House, takes this premise and uses it to tell the story of her own experience in an emotionally and psychologically abusive relationship, as well as the story of our larger failure to come to grips with intimate partner abuse in queer relationships.

Like her debut story collection, Her Body and Other Parties (a National Book Award finalist and Lambda Award winner), In the Dream House interrogates and innovates familiar formal tropes. Each chapter refracts Machado’s experience and research through the lens of a trope, form, or genre; each chapter is named after a literary device: “Dream House as American Gothic,” “Dream House as Queer Villainy,” “Dream House as American Gothic,” “Dream House as Noir,” and so on.… What might feel gimmicky in another writer’s hands is revelatory in Machado’s: In the Dream House becomes a complexly layered exploration of the personal and the political, and the literary, both a brave baring of a painful experience and a reckoning with our collective failure to truly deal with queer intimate partner abuse.

These chapters are not exercises in style for their own sake; they point to the ways in which tropes and clichés haunt us, how they structure–and sometimes limit–the language available to us (particularly queer folks) to describe our experiences. Machado describes how she found it difficult to think about her abusive partner as an individual, without also thinking about the clichés and stereotypes that many of us grew up with:

Narratives about mental health and lesbians always smack of homophobia. [….] I haven’t been closeted in almost a decade. Even so I am unaccountably haunted by the specter of the lunatic lesbian. I did not want my lover to be dogged by mental illness or a personality disorder or rage issues. I did not want her to act with unflagging irrationality. I didn’t want her to be jealous or cruel. Years later, if I could say anything to her, I’d say, “For fuck’s sake, stop making us look bad.”

In the Dream House argues that Machado’s reluctance to identify her abuser’s mental illness is part of a larger pattern of the queer community’s reluctance to talk about abusive relationships. Machado is intensely sensitive to the reasons for this: she explores not only the long history of heteropatriarchy’s inability to comprehend either love and sexuality between women, or women’s rage and violence–let alone all of that together. But in addition to that long history, Machado parses our contemporary reluctance to talk about abuse. In part, it has to do with letting go with the idea that queer people are different (read: better) than straight folks in this regard:

The literature of queer domestic abuse is lousy with references to this punctured dream, which proves to be as much a violation as a black eye, a sprained wrist. [….] Acknowledging the insufficiency of this idealism is nearly as painful as acknowledging that we’re the same as straight folks in this regard: we’re in the muck like everyone else. All of this fantasy is an act of supreme optimism, or, if you’re feeling less charitable, arrogance.

Her sensitivity to both the inter- and intragroup factors leading to the marginalization of abuse narratives and abuse victims are part of what makes In the Dream House compelling and timely.

Genre and form play a role here, too. Machado’s skillful retellings and reimaginings of folklore—be it urban legends or Law & Order: Special Victims Unit—were part of what made Her Body and Other Parties such an extraordinary collection. In her memoir, her fascination with tropes is again on display. Machado shows over and over in each chapter how their power becomes amplified for queer people (and other marginalized groups): lacking the same breadth of representation in popular culture that straight (and white, and cis) people get, every iteration of the lunatic lesbian or the evil queer feels weighty and significant, rather than one of just many possibilities of expressing our humanity. Writing about the contentious subject of queer villains, Machado argues that

[…] by expanding representation, we give space to queers to be—as characters, as real people—human beings. They don’t have to be metaphors for wickedness and depravity or icons of conformity and docility. They can be what they are. [….] And it sounds terrible but it is, in fact, freeing: the idea that queer does not equal good or pure or right. It is simply a state of being—one subject to politics, to its own social forces, to larger narratives, to moral complexities of every kind.

This, too, is what In the Dream House seeks to accomplish: to explore the full range of queer humanity, good or bad.

In praising the book’s aesthetic and critical qualities, it is important not to lose sight of Machado’s subject–intimate partner abuse. Part of what makes In the Dream House so devastating at times is how well it captures the truly damaging nature of emotional and psychological abuse: it functions by making the victim doubt her own feelings, her own grasp on reality. Machado describes how the effects of those dynamics continue long after the relationship ends (Was it really that bad? Was it actually my fault?), and how her own doubts become amplified by the doubts of those around her, who openly wonder if it wasn’t all just an exaggeration. She writes,

You have this fantasy, this fucked-up fantasy, of being able to whip out your phone and pull out some awful photo of yourself, looking glazed and disinterested and half your face is covered in a pulsing star [….] Clarity is an intoxicating drug, and you spent almost two years without it, believing you were losing your mind, believing you were the monster, and you want something black and white more than you’ve ever wanted anything.

Part of the problem, In the Dream House argues, is that our understanding of the full possibilities of what abuse might encompass are dangerously limited, particularly when it comes to queer relationships. In looking through the relatively limited body of literature on queer abusive relationships, Machado finds that most of the experiences of queer folks have been lost to history:

[…] the nature of archival silence is that certain people’s narratives and their nuances are swallowed by history; we see only what pokes through because it is sufficiently salacious for the majority to pay attention. [….] Narratives about abuse in queer relationships—whether acutely violent or not—are tricky in this same way. Trying to find accounts, especially those that don’t culminate in extreme violence, is unbelievably difficult. Our culture does not have an investment in helping queer folks understand what their experiences mean.

In the Dream House speaks back against this archival silence, offering up an account of a relationship that is in many respects very ordinary. To call it “ordinary” is not a critique or a trivialization–it is very much the point. Abusers, she reminds us, “do not need to be, and rarely are, cackling maniacs. They just need to want something, and not care how they get it.” Reconceiving of abusers in this way is not to exculpate or excuse; rather, it helps us see the full range of abusive behaviors that people experience every day. To quote “Dream House as Epiphany”–a chapter comprised of a single, devastating sentence–“Most types of domestic abuse are completely legal.” In the Dream House does not ask us to look away from physical or sexual violence; rather, it shows us that these acts comprise the extreme end of a continuum of many behaviors that have been, if not largely overlooked by those who have not experienced them, normalized or trivialized. It asks us to look beyond the clichés and tropes that structure popular understandings of what constitutes abuse.

The intertwining of critical insight, personal narrative, and aesthetic innovation alone makes In the Dream House an incredible, exciting read from a talented author. But it’s not only that that makes the book an important one, and especially for the queer community. The dynamics Machado describes were familiar to me from personal experience, and once I’d finished the book, I pressed it into the hands of another queer woman, who had been in a relationship much like the one portrayed in the book. It was hard to believe that so few books have been available for us to describe that experience–the confusion, the invisibility, the anger, the grief, the warped sense of reality. In the Dream House begins to give a rich, vibrant language, a structure for understanding for that experience. And more than that: it made us feel seen.

In the Dream House

By Carmen Maria Machado

Graywolf

Paperback, 9781644450031, 264 pp.

November 2019