The Author That Raised Me: Thoughts on the Passing of Toni Morrison

Author: Frederick McKindra

August 15, 2019

Toni Morrison’s work was difficult, always. It was also, simultaneously, so familiar; I recognized myself, a young black gay man, in it immediately. That always astounded me, how well she knew me. That’s why she felt like such a thoughtful, but stern, parental force. Even when I didn’t understand it, her work was patient and didn’t laugh at me, was willing to suffer my frustration to claim it and my lies about knowing it better than I did. Her work made a boy out of me, always—made me feel that kind of awe, but also that I was known and cared for, somebody’s. And God, did I love her for being there, every time the world didn’t treat me special. Or kind. Or even recognizable. I read her to feel loved by somebody.

She was hard. I’ll always honor her by aspiring to her. That’s what I want her to know I’m doing, not sitting in awe of her, not appreciating her. I want her to know that the black kid she inspired, who she seemed so desperate to make a world for, is out here working still. That what she did helped me recognize myself as a writer, and that such a recognition proved sturdy enough to withstand a career that has been quite hard.

What she inspired in me was sturdy, not brittle, not weak. I miss her for that already. That she was such a tough guiding light, but one that forced you to sit up straight, if you approached her work too early, or with too much pride, or without serious enough intent, or before you’d lived long enough to grow, out of necessity, a wry sense of humor.

Toni Morrison’s father and mine were similar in that they were suspicious of living in too close proximity to white people. African Americans that close to a life of subsistence farming have an unrelenting pride. They do not suffer haughtiness, not from Chocolate City Negros from Chicago, DC, Harlem, Detroit, nor Atlanta. And certainly not from mediocre white people whose egos need a stepping stool.

Her father wouldn’t let them in his house. Mine wouldn’t let me attend their colleges. Morehouse hadn’t produced any Toni Morrisons, so I went to Howard, because she’d gone there. She literally meant that much to me then. For a while as a student at Howard, this meant everything to me, was my one consoling thought about the place. Ironically, I hated the omnipresence of her work in the English department, thought it would’ve offended her, in fact. I hated that the school trotted her legacy out so cavalierly whenever it needed reminding that writers had once, long ago, inhabited this place too. She herself appeared once on campus during my tenure, for a Heart’s Day Ball, but I stayed away, perhaps because the tickets were too expensive, or perhaps because I hadn’t signed up early enough for the student pass. Perhaps I was angry with her for not being there more often.

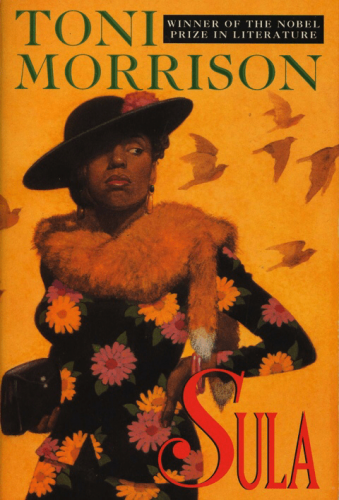

Sula had already become my first love story by then. I gave a paperback copy of it as a parting gift to the first guy I ever fell in love with, in high school, at writing camp, when I was 16. I’d never let myself feel  anything like love before then, too desperate to become the kind of black boy my family and community would feel proud of. I remember checking the novel out from the library of the college where we were staying because I was terrified, the only black guy in the program, sure I wasn’t smart enough to be there, and catching feelings for this white dude hard. I went to get a book because I literally needed to calm myself down, to sit by myself and read, like I was burning too hot and needed a container to pour some of myself into. Also, I wanted something fancy, something that could restore my faith in myself for being there. That’s how I found Sula, nothing more mystical than that. I went searching for her in the stacks cause I needed somebody to validate me, and my ambition, and my burgeoning same-gender-loving body, and there it was, waiting. I loved that cover, the one by Thomas Blackshear, with the dark skinned woman with the asymmetric hair and the jaunty hat and the side eye with the fox stole with her hand on her hip. That image made me feel powerful. The book was even better.

anything like love before then, too desperate to become the kind of black boy my family and community would feel proud of. I remember checking the novel out from the library of the college where we were staying because I was terrified, the only black guy in the program, sure I wasn’t smart enough to be there, and catching feelings for this white dude hard. I went to get a book because I literally needed to calm myself down, to sit by myself and read, like I was burning too hot and needed a container to pour some of myself into. Also, I wanted something fancy, something that could restore my faith in myself for being there. That’s how I found Sula, nothing more mystical than that. I went searching for her in the stacks cause I needed somebody to validate me, and my ambition, and my burgeoning same-gender-loving body, and there it was, waiting. I loved that cover, the one by Thomas Blackshear, with the dark skinned woman with the asymmetric hair and the jaunty hat and the side eye with the fox stole with her hand on her hip. That image made me feel powerful. The book was even better.

The love I was feeling that summer was already doomed, just like Sula and Nel’s, and I knew it, even then. I gave the book to that boy anyway, hoping Nel’s fate at the end of the novel might keep us from losing contact once we’d returned to our homes. I remember desperately wanting him to read the line concerning Ajax and his use of the word “pigmeat,” how vulgar and also how inexplicably right it was. That was exactly what I’d been feeling that summer, something vulgar and also right.

In return, that boy gave me Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha, which is hilarious. Like Siddhartha, that boy wanted his freedom, to become an individual. I, like Siddhartha’s friend Govinda, wanted us to become acolytes and grow old side by side. Like I said, that love was doomed.

I can’t find the quote now, but somewhere Toni said she was so brutal to her characters because how else was her audience going to learn. I knew then that she would’ve found me insufferable, and that she’d meant that crack just for me. But that’s also why the world seemed scarier the day she died. I hardly ever trust my own instincts on race matters, on black community. I always suspect I’m the Uncle Tom in the room, the one with compromised loyalties. I’m the one who thought Ellison had rightly titled his book Invisible Man. So without Toni, who else was gonna shake sense into me? Who else could I trust, even if I was always getting her wrong, misunderstanding her. The things I did to make her proud were often insufficient, or wrongheaded. I didn’t trust that I’d learned enough yet. Still, she was gone.

She defied so many black pieties, but chief among her defacements was her willingness to present black elders as flawed sometimes, an offense to that most ancient of black folk wisdoms about respecting one’s elders. As a black gay man, that was the single thing I most feared ever doing in life. It was also the thing I knew I had to do. She gave me the characters to imagine a life I could lead that would sometimes appear impolite, crude, or even stubborn. And these characters dared live their chaotic lives in full view of black community. Even her language, which was figurative, metaphorical, ambiguous, and lyrical, was the vernacular tongue of the same black community I’d long feared having to flee in order to be my full self. Reading Baby Suggs exhort her fellow slaves in Beloved to touch themselves because they’d forgotten what it felt like to have a body, to be human, was the key to throwing off the yoke of having been raised in the black church, freeing oneself of the shame such a place could attach to your body, so much that you wanted to forget you even had one. Reading black elders depicted so profanely, who were cruel, and covetous, and who fucked, gave many of the black queer people that loved her work permission to stay, to imagine a black community they were allowed to inhabit because black queer people had always been there.

So much of what Toni’s novels had to say to me had to do with place, landscape: her novels were mostly rural novels to me, where black people had lived before migrating to cities; where they were forced into community, and consternation with one another. And where their idiosyncrasies had enough room to grow to outsize proportion. There was none of the weathering down of sharp edges or behaviors that the density of cities did to black transplants. In rural space, black people were less concerned with white people, performing for them. Also, they couldn’t abandon one another because where would that person have gone. Leaving someone to fend for themselves would have been unconscionable. I think that’s why she seems so important to black letters, because in some way, she was illuminating a seminal snapshot of black history, post-slave trade, and she seemed committed to capturing it before urban life claimed all of us, subsumed black identity altogether. Even Baldwin, though only seven years Morrison’s senior, bracketed his father’s Southern origins in an aside, and resolutely trained his eyes on black urbanity. Without Morrison, that mythic tie to the land would have been lost.

I think I learned it was okay to resent my father from Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, but reading Morrison’s Paradise helped me understand him. She did it in a way that still astounds me. Rather than console me over a history spent withstanding the authority of someone who’s personhood was so distinct from my own–whose radical communitarian commitment to black community often made me feel denied opportunities to advance my own stake–she ennobled his haughtiness, his pride, so that I might know better what it meant to derive from a segregated society, a proud black self-sufficient unit that would never value white America above what it had itself made.

That’s why I quarreled with her, mostly because she poured so much of herself out to Princeton, that “northernmost outpost of Southern culture,” the University of the antebellum planter class. When she gave them her papers, I was furious. That institution didn’t deserve her, though she certainly deserved their patronage. She, like so many of her black public intellectual contemporaries, seemed okay with letting the Humanities at historically black colleges wither, while universities with big endowments, coffers fattened at some point by slave money, paid them handsomely. At Howard, I remember lamenting the fact that none of my heroes wanted to teach me, seemed more excited to serve as nursemaids to Ivy Leaguers.

But Eva’s ultimate lesson to Plum, her doted-upon son in Sula, always felt personal to me, because Toni would forever deny me any self-pity. She meant that story as my warning. I imagine her snorting with laughter at my scorn, at how tired my black nationalist separatism would have seemed to her, and how insufficient it was probably in the face of her needs, or even her want to have some pleasure or comfort, to be paid what she deserved. I imagine her warding me off clutching her skirt hem too hard. She knew my love was fickle, knew not to depend on the whims of those that claimed to adore her. She wrote Eva to signal that she didn’t owe me her life, and that she wasn’t gon give it.

Heeding her advice hasn’t always worked like I planned. Because what if I wrote the novel that I wanted to read, just like she’d said, and none of the big publishing houses wanted to publish it? What then? What if the things I wrote were too gay, or too black, not commercial enough? Or what if it was none of those things, what if I just worked the material until it was over-written, full of sentences that sweated, because I’d wanted them to say what she’d said when she said, “pigmeat.”

I want Toni Morrison to know how sturdy her inspiration has proven to be, even though I’ve come to know better the lasting consequences of a writer’s life, of doing language. I’m grateful to her for the way she constantly challenges me to confront my ideas about blackness, about black community, about disbelieving the myths projected onto black people, and sometimes the ones in which we imprison ourselves.