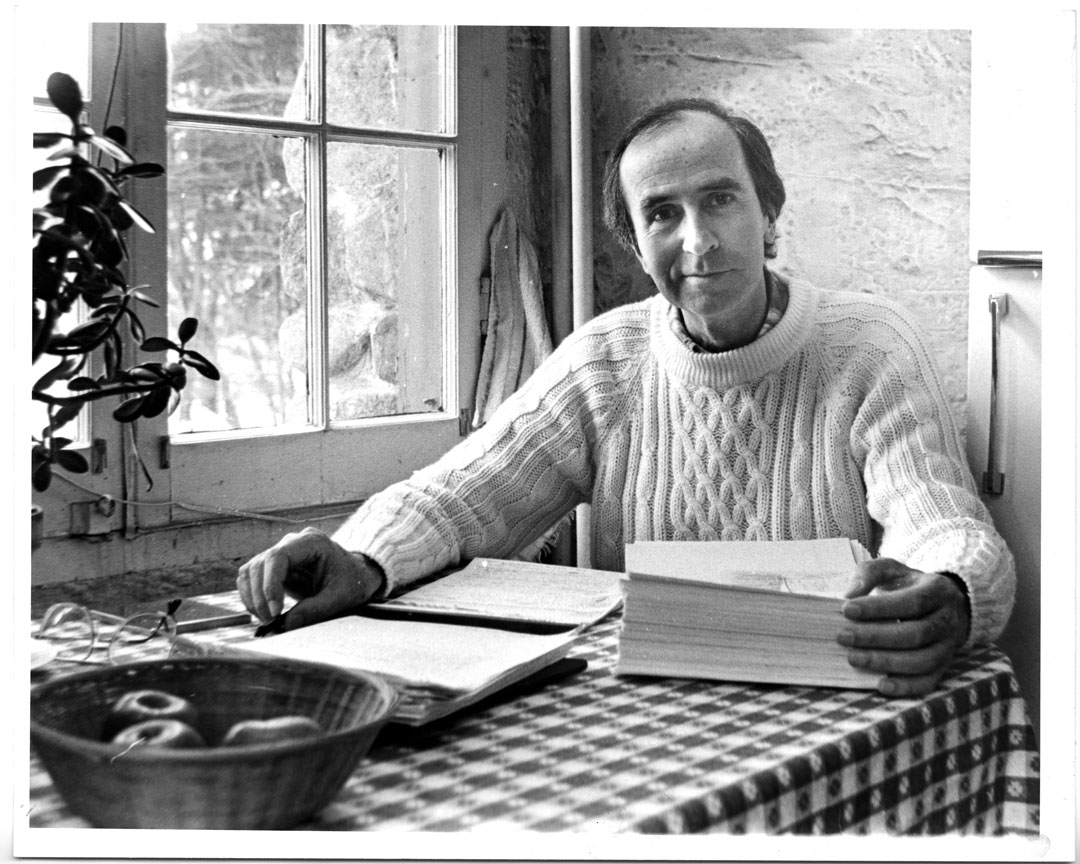

Novelist and Poet Michael Rumaker, 87, has Died

Author: Edit Team

June 12, 2019

Writer Michael Rumaker, 87, has died. The author died on June 3, 2019, at Jefferson Washington Township Hospital in Sewell, NJ from natural causes.

Born in Philadelphia on March 5, 1932, Rumaker was a graduate of the famed Black Mountain College (1955) and Columbia University (1970). An author of over four books, the majority of Rumaker’s writing centered on his experiences navigating both the postmodern literary scene and his queer identity.

Via publisher Spuyten Duyvil.:

[Rumaker’s] first book, The Butterfly, is a fictionalized memoir of his brief affair with a young Yoko Ono, published before Ono became famous. His short stories, Gringos and other stories, appeared in 1967. A revised and expanded version appeared in 1991. He began to write directly about his life as a gay man in the volumes A Day and a Night at the Baths (1979) and My First Satyrnalia (1981). The novel Pagan Days (1991) is told from the perspective of an eight-year old boy struggling to understand his gay self. Black Mountain Days, a memoir of his time at Black Mountain College, has a strong autobiographical element. In addition, there are portraits of many students, faculty, and visitors (especially the poets Robert Creeley and Charles Olson) during its last years, 1952-1956.

In remembrance of Rumaker’s life and legacy, we are honored to share an interview, conducted by Tom Cardamone, that was published in the 2011 spring issue of Mary Literary.

*

Author Michael Rumaker has published novels, plays, poetry, and a memoir, Black Mountain Days, about his studies at the famous liberal school, Black Mountain College, in North Carolina, now closed. From the birth of Beat poetry to the gay rights revolution of the 70’s, Rumaker offers the reader more than the perspective of a witness, he shares songs of experience.

His seminal work, A Day and a Night at the Baths, is back in print after more than 30+ years. Sure, A Day and a Night at the Baths has quite the self-explanatory title, but don’t pigeonhole this book as a steamy artifact of 70’s pulp. Sexual transactions can be complicated, sticky, arduous, and especially difficult and revelatory during a transitional period of intense repression and discrimination. The poetry of the body, lust, desire, and the urban tribe are all here, making this first-person erotic adventure at the infamous Everard Baths more journey than journal. Anyone would be hard-pressed not to read it in one sitting.

One thing that surprised me about A Day and a Night at the Baths was that the main character comes across the scene of a suicide before entering the baths: someone has jumped from the Empire State Building, alternately described as phallic and a symbol of cold capitalism in the book. He automatically wonders if the man who killed himself was gay. I’m curious about this linking of Eros and Thanatos…

Well, as I wrote in one of my poems, “Sex is the consolation prize for death.” The French call the male orgasm “la petite mort,” the little death. And British scholar Jonathan Dollimore published a book in 1988 linking Eros and Thanatos, titled Death, Desire and Loss in Western Culture, in which he cites, among others, my A Day and a Night at the Baths, along with John Rechy’s The Sexual Outlaw, both books published in the late 1970s, to bolster Dollimore’s thesis of the two faces of the same coin: the death instinct (“death” in Greek and “vanishing” in Sanskrit) and the pleasure principle. Although the narrator, describing the results of the suicide in the deeply dented marquee of the Empire State Building and his speculative guess that the victim might be a frightened and despairing gay man, ties in with the theme of death and desire that the narrator later experiences which thread through the book, as evidenced in the fears and dangers, including multiple diseases, at the baths, all of it is rooted in the conscious and unconscious mind of the protagonist.

I’d read that the book’s initial form was as a poem. And since the book is partly autobiographical, I’d like to know why you chose to tell this story in the form of a novel…

As I said in an earlier interview to the same related question: “Some [of my] prose works have started out as poems, such as A Day and a Night at the Baths and My First Satyrnalia, but [as in those particular instances] I’d seen pretty quickly that, because of their growing length and the increasing amount of detail, plus that the poems were actually taking the shape of autobiographical stories, they really needed to be prose works… [T]he poem often led me to my better half, narrative, and often thereafter, inspiration that started out as long poems really served as the kick back to the track where I had surer footing—story….”

Did you visit the baths often?

Of course writing a book about the baths required a great deal of field-work, ahem. You want to get the details right. After my initial visit, on which the book is largely based, I spent many subsequent visits scribbling away in my notebook on the thin, grimy mattress in any number of grim cubicles. A Day and a Night at the Baths was largely written within the walls of the Everard Baths. It took many visits: after all, since I was no longer a youngster, I had a lot of bath-time to make up for. The sexual experiences freely available there were certainly an intoxicant. Having a healthy sex life is a necessity for every human being, emphasis these days, as we tragically have learned, on healthy.

It’s hard for younger readers to imagine the immense silence that was homosexuality just a few decades ago. And that the baths were these unique places you could enter, exiting oppression and within a minute be surrounded by naked men and even more naked lust—I think this dichotomy is nearly unimaginable today.

Yes, the baths were certainly a paradise, despite everything, an oasis of escape in the midst of the dangers in this most rabidly homophobic nation.

Awhile ago I made a visit back to one of the few remaining bath houses in New York City, mainly to see what was going on, and the place was jumping, humming with erotic play. My view was subjective of course, and, hence, limited, but I noticed a lot of safe sex going on, including intercultural sex. Folded into my bath towel handed to me on arrival were two condoms and two packets of lube, a noticeable change from the old days.

Thank Priapus that “dichotomy” and “immense silence” no longer exists, thanks largely, too, to our own efforts to rid ourselves of them.

The book details cruising and bath house etiquette. Did you check out other bath houses? Were there different forms of communication in difference spaces?

To visit as many bath houses as possible was certainly a strong temptation. The main difference among them was not so much “forms of communication” as differences in atmosphere: The Everard, the queen, if you will, as the oldest baths in Manhattan, was also the darkest and grungiest, which I think I’ve made clear in “Baths”; the brightest, more warmly inviting, was the Club Baths on First Avenue; it also boasted the youngest and most attractive clientele. But the erotic gestures and signals, the pleasures that call loudly to us all, were largely the same in each.

Tell me about the process getting Baths back into print.

Even though the novel continued to sell well into the 1980s, the publisher of Grey Fox Press out in Bolinas, California, Don Allen, with the early advent of AIDS, paid heed to his lawyer’s advice to yank the book. Over the years I attempted to get it back into print with other publishers but was turned down again and again, including by Barney Rosset of Grove Press, who’d published my Gringos and Other Stories and many of my poems and stories in his Evergreen Review. He wrote me, on receiving the manuscript, “What do you expect me to do with this?” Well, I thought, “if you don’t know, Barney….” The gay publishers were equally blind and deaf, including Felice Picano, publisher of the new gay male-themed Seahorse Press in New York, who turned thumbs down.

I had given up all hope when several months ago I got a message out of the blue on Facebook from the editors of Spuyten-Duyvil Press, saying they liked my work, and did I have anything for them. I immediately offered Baths, which they accepted to my great pleasure and relief. Coincidentally, just a week before hearing from Spuyten-Duyvil, I’d been tinkering with the idea to cancel my Facebook account—Maybe, though, I’ve been one of the first writers to get a publisher on Facebook!

You followed A Day and a Night at the Baths with the aforementioned My First Satyrnalia. Please tell us about the inception and life of that book.

One day in 1979, by luck, I saw a small card announcing the formation of a Fairy Circle in Manhattan tacked on the bulletin board in the rear of the late and still-much missed Oscar Wilde Bookshop on Christopher Street in the Village. Intrigued, I decided to attend. The highlight in those early days of the Circle was an evening celebrating the Winter Solstice in a loft down in the East Village. That ritual-filled event of singing and chanting, raising moon and sun, raising ourselves, and testifying out loud our inner-most selves, was so electrifying to me that I sat down at my kitchen table when I got home and wrote all about it. The result was My First Satyrnalia, which publisher Don Allen also published in 1981, in his Grey Fox Press out in Bolinas, California.

In the afterword to Baths, you mention the writer Richard Hall. Allen Ginsberg reviewed your work and offered a comparison to Walt Whitman. As you wrote and published, which queer writers in the ’70s and ’80s were you drawn to—who among them were your peers that you could talk shop with?

Actually, the gay writers I was close to and “could talk shop with” started for me at Black Mountain College in the western North Carolina hills, in the early 1950s with fellow students Jonathan Williams and John Wieners and San Francisco poet Robert Duncan. A little later, in Manhattan, there certainly was Richard Hall and Allen Ginsberg and any number of others at that time, both in New York and San Francisco. There were also non-writers, such as Jim Naismith, a gay mentor to me in a way, who encouraged me to overcome my fears and make that first trip to the Everard. He also suggested I write about it. Jim was also a close and dear friend who saved my life at one point. He was married with three daughters, and yet, like Paul Goodman, openly gay. Also, paradoxically, his grandfather, James Naismith, invented basketball.

How did he save your life?

By 1973 my alcohol and drug addiction had gotten so extreme, I was told by the medical people I hadn’t long to live. I had hit a hopeless bottom and didn’t care. But Jim, just about the only friend I had left, kept coming to check if I was still alive, and finally came on the morning of June 20, 1973 to the little rat-infested boat house I lived in on the Hudson River in Grand View, New York, and hauled me from the bed where I’d been lying comatose for days and hauled me off just in time to a drunk farm, High Watch, in Kent, Connecticut. It was there, after a couple of months of good medical care and good food, when I was finally able to keep something down, that I was freed from years of the tyranny of booze and drugs.

Jim died of a heart ailment a few years ago, at home in West Nyack, New York, surrounded by his partner, Gene, of many years, by his wife, his three daughters and his grandchildren. His ashes were scattered in the Hudson River, along the trail he loved to hike at Hook Mountain. I miss him mightily.

Did you have any connections with the Violet Quill writers and what did you think of their work?

No real connections (I’ve already mentioned Felice Picano, a member), but I’d met Robert Ferro and Michael Grumley of that group, who were a couple, met them in the middle of Fifth Avenue during the June Gay Pride March in 1980 in a bunch of us gay authors who were marching together on our way to take over the steps of the Fifth Avenue Library. Robert and Michael both enthusiastically told me how much they loved Baths. I liked them both very much; they were so warm and open, so genuinely friendly, and damned good writers. Sadly, both later died of AIDS while still young.

Are you interested in anyone among the current crop of gay writers?

I expect it’s my age—I’m 78—so it will be easy to dismiss anything I say about “the current crop of gay writers” as gaga or “old hat” (the latter, words used recently by an anonymous critic of the new edition of Baths); or “old-fashion,” another barb aimed at my writing in general, as well as my scribbling, after over half a century, “not having aged well.” I don’t have the ability anymore to read as much as I used to, or would like to, although I find that a great deal of what I do read strikes me as flat-liner prose and poetry: no rhythmic magic in the lines, no sense of genuine love of language and what it can do. But then, as I said, old geezers tend to be dismissed, most certainly in the queer world. You reach a certain age, you become invisible. (I’ve been thinking of writing a novel, a switch on Ralph Ellison’s title, Invisible Man, called Invisible Fag.) Well, enough said about that.

You dated Yoko Ono. What was your relationship with her like?

Yoko has been much maligned, unjustly so. The time I spent with her was with a very intelligent and imaginative young woman, with strong innovative impulses, a stimulating and pleasurable companion, and that despite her troubled dark side, which I could strongly empathize with, facing demons of my own then. I can see why John Lennon was so attracted to her; they were perfect mates, who fed each other’s genius.

I wrote about our brief affair (affairette?), which lasted from winter 1960 to late spring 1961, after our breakup, in a novel titled The Butterfly, before she was world known.

How did you meet? Did you come out to her?

I first met Yoko Ono at a large Saturday night party of artists and writers and musicians in Stony Point, New York, in the winter of 1960. In the spring of that year I had been released from a two-year confinement after a breakdown at Rockland State Hospital in Orangeburg, New York, and was recuperating from a long bout with deep clinical depression and anxiety, from which I suffered periodically since when I was a child. The 1950s and 1960s were the dark days of enforced heterosexuality in a rabidly homophobic society; the guilt and pressure and the need to hide certainly helped trigger those breakdowns in adolescence. At the time I’d met Yoko, I’d been under the care of a psychologist at Rockland who, like most psychiatrists and psychologists at that time, strongly held those anti-gay views and who believed that queerness could be “cured” for the male by finding the right female. Such erroneous and barbaric ignorance caused what I can only term “post-traumatic stress,” which was what I was still undergoing the night I first met Yoko. When I got to know her and we began to confide in each other, she told me of her own bouts with depression and her own suicidal thoughts, which enabled me to empathize and identify most powerfully with her.

She was at the party with several of her Japanese male friends, including her first husband, Prince Toschi, musician and young son of the Emperor of Japan. They had brought along a sitar, a long-necked lute which was played while seated on the floor. I noticed this small, sober-faced young woman with long black hair who, instead of listening to the music, was intently staring across the sitar at me. I returned her gaze and after the music, she approached me and started a conversation in a soft, measured voice. I was immediately captivated by and very curious about this quietly contained and puzzling woman. She gave me her phone number and invited me to visit her loft and studio down at 112 Chambers Street in Lower Manhattan, where she was creating her early Fluxus and Conceptual Performance works—seated staring into a bowl of string beans, for one.

Toshi and her friends, she told me later, were scandalized when she approached me and began a conversation, a transgression that was evidently frowned upon in traditional male-dominated culture. Toshi especially reprimanded her, but Yoko had, as I came to learn, despite her quiet manner, a steely mind of her own and ignored the criticism.

At first, we saw each other several times for dinner in the Village and the occasional movie, and soon we became intimate, which delighted my homophobic psychologist to no end, who, encouraging me to keep at it, pronounced that I would be “cured” quite soon of my queerness.

Yoko assured me she used birth control and not to worry, but several years later when Albert Goldman interviewed me for his book The Lives of John Lennon he intimated that that had been a consistent pattern with Yoko, the number of males she had been involved with before I came along she had also suddenly broken off with when, having lied about using birth control, she found herself pregnant and would, according to Goldman, in those days since abortion was illegal, find a doctor to get rid of it. How true this was in our case I don’t know, but if it were true, it would explain her abrupt and unexplained break with me.

Although there might have been another reason: later, after she met Lennon, they were interviewed by Playboy in the November 1980 issue. When Yoko was asked if she’d had affairs before meeting John, she admitted she did, saying that in one of them she discovered the young man “was a homosexual,” which I suspected could only mean me. Goldman’s theory aside, that was probably the actual reason for her dropping me. How she “discovered” that I’m not sure; she being a very perceptive person, she probably figured it out on her own. But I know by the time I met her, there were many who knew or who heard rumors, and I expect tipped her off.

I was duped into thinking my queer self was hidden as to be almost invisible, but there were always those quick to spot it. Then, too, in the swarm of disgust in which homo hatred was and still is based, all of it deeply entrenched in religion, the law, and the so-called “helping” professions of psychiatry and psychology—our greatest enemies then and now—where homosexuality was considered a very sick and very dangerous pathology, both a mental illness and a crime, that could incarcerate you either in a mental hospital or in prison, like so many of my generation at the time, I put on a straight false-face and kept a close eyes on my mannerisms. I wanted to be straight, believed it would make my life easier, make me easy within myself. But of course I was only fooling myself: Eros and the craving for love of another male were more powerful than homophobia, any religion or law or psychology, more powerful than my own or any others’ denial.

I wanted desperately to succeed with Yoko, and the psychologist, who had a great Svengalian influence over me, continuing to insist, like other therapists, that I was not homosexual, pressured me to succeed, continuing to say things like, “Why do you want to suck a dirty old cock for anyway?” that root again of disgust, so that he even had me believing it myself, knowing that same-sex experiences were wonderful, denying the truth of my own body.

So I never really “came out” to Yoko, was afraid to, of losing her, trapped as I was in fear and mistaken identity, ignoring another truth: that I was using her.

What was it like to participate in as well as witness the birth of new poetic forms: the beats and postmodernism?

I sometimes jokingly say, since the term has become overused for everything, from soup to nuts to poetry, and wish Charles Olson had never dropped the word “post-modern” in that 1952 or 1953 letter to poet Robert Creeley, who was busily corresponding with Charles on his chicken farm up in New Hampshire and setting the tone, along with Olson, for much of the dynamic changes in poetry in the last half of the twentieth century. Still very “wet behind the ears,” as my ship fitter father used to say, I certainly felt a mere sapling in the company of those two sequoias (not to mention Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg and Denise Levertov, to name a few).

I was a slow learner when it came to the exciting, innovative writing of the day, writing that opened up new ground and stretched the horizons. As you can see in my 1957 critique of Ginsberg’s “Howl” (with a sideswipe at Jack Kerouac) in last issue (No. 7 1958) of The Black Mountain Review, whatever breakthroughs I achieved in my writing came painfully slow, incrementally so, over time. But I eventually got it. I later wrote an amends on that great and influential poem, and Allen and I remained good friends for the rest of his life.

I write about this in my memoir, Black Mountain Days, regarding my torturous apprenticeship with poet Charles Olson, when I was a very green student of his at Black Mountain College in the early 1950s. Some are quicker than others, like fellow BMC student poet Ed Dorn (we were the last two of three graduates in 1955–no easy job–at that tiny magical college in the mountains of western North Carolina; my outside examiner was poet Robert Duncan, then living in Majorca, Spain), but that wasn’t my rhythm or speed; however, it was hard a struggle, but I eventually got my eyes and my ears open, with especial thanks to Charles.

I’d like to close with a quote from A Day and a Night at the Baths, and would love for you to offer further insight into the scope and meaning of these words:

“Let me not be ‘Good”—Let me be fierce, bright and untamed, pitiless, with the open unblinking eyes of the Kwakiutl bird-head behind my falseface. Let me plunge in my oceans, plummet into my trees, tend to the wild gardens of myself, the wilderness forest and jungles where my untamed animals prowl, silent and sleek and singular, strong in beast-spirit, supple and curvaceous in the sprite of the unbent tendril and vine. And in the small plums that are nipples, and the apples of the thighs—Fruits are delicious.

-Thank Eros, we are.”

Well, I’ve often taken heed of D. H. Lawrence’s advice: “Never trust the writer, trust the tale.” But, hell, this question’s too tempting to pass up.

What I see in the above quote is a fierce hymn and a chant to the wildness within, to the untamed self, to the spirit of the sacred in the natural earth as opposed to the supernatural, as opposed to the tamed and beaten self, the craven mind and spirit of the slave, which is everywhere today; a hymn and a chant to the riches of the imagination and of making, and to being alive in every fiber of my being and every moment of my life. No more a life “of quiet desperation.”