Academia and Queerness in Buffalo, New York During the 1980s

Author: Rebecca Allan

March 20, 2019

In September 2018, Spuyten Duyvil released Buffalo Trace: A Threefold Vibration, a collection of essays about coming of age at the State University of New York (SUNY) Buffalo’s storied English Department during the 1980s. A compelling mix of critical theory and personal remembrances, Buffalo Trace maps writers Mary Cappello, James Morrison, and Jean Walton‘s experiences navigating academia and queerness, during a moment of both extreme social strife and innovative intellectual inquiry.

Writer and critic Phillip Lopate notes:

At a time when the university humanities are under siege, this heady, fascinating trio of novella-length autobiographical accounts of grad school literary studies is an absolute treat: bracingly honest, self-aware, witty, probing, exquisitely written, lucid and humane. What’s been missing in most current memoirs is the subjects’ intellectual growth, alongside their traumas or sexual adventures. This book has it both ways: the romance of learning and pedagogy merging with an education in eros.

In this interview, conducted through email, artist Rebecca Allan asked the coauthors about the creation of the book, revisiting Buffalo, and coming to queer adulthood in the 80s.

Mary, James, and Jean, thank you for the opportunity to delve into your book Buffalo Trace: A Threefold Vibration. It has been a pleasure for me to (re)visit Buffalo, the city where I grew up, through your insights, recollections and ruminations. I’d like to begin by asking you to talk about your catalyst for writing this book. And, in contemplating the format and tenor of the project, did you think about particular literary predecessors, or memoirs with more than one contributor?

Mary, James, and Jean: We wanted to create a multi-perspectival take on the subject of coming into queer adulthood in a time and a place that might seem inimical to that—in our case, 1980s Buffalo where we came together as graduate students in SUNY/Buffalo’s famous English Department, known then as a cauldron of deconstruction, psychoanalysis, and experimental poetics. Our desire to articulate distinctly queer attachments to books and ideas is couched in this sense that queer love makes new forms of friendship possible—between men and women, we three, included.

There are a number of tripartite queer precursors that we love and hoped to sound in our own “threefold vibration,” from Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives to David Plante’s Difficult Women, to Hilton Als’ The Women, to Roland Barthes’ Sade, Fourier, Loyola. At the same time, we were startled to realize that there was no precedent (that we knew) of a book that was a triptych of meditations by lesbian and gay writers in conversation.

The unfolding of your lives as graduate students in the English Department at SUNY/Buffalo in the early 1980s was interwoven with that city’s painful economic decline and resulting decay of its once-glorious infrastructure. Given your immersion in learning, and the excitement of exploring your interior and social lives as young writers, how did these external changes impact your work or your thinking?

Mary, James, and Jean: The experience was that of pursuing a “cosmopolitan” discipline in a marginal location. However Buffalo fashioned itself the Berkeley of the East or a bush-league Yale, you could never really lose sight there of the oddity of the whole enterprise of literary study, because you were always face to face with real struggles–from local residents’ efforts just to get across town in a blizzard, to the rising tide of homelessness that swept Buffalo in the Reagan years, as it did everywhere else. Nobody could burrow too far into an ivory tower in the City of No Illusions. Since we each also brought different versions of our own modest upbringings with us—from Detroit, Philadelphia, and Vancouver, BC—Buffalo’s own lack of polish provided a kind of recognition mechanism for we three. It reminded us to “keep it real” and not give in to amnesia no matter how heady we might become.

Your book is not only a discourse on the worth of the writer’s métier, and the life of the mind, but also a shared reflection on the value of education, especially in the arts and humanities. Could you revisit an experience that exemplified a moment of learning that immeasurably shaped you during those years?

Jean: My “instruction” at Buffalo (by predominantly male professors) was always routed through my own unconscious processes before a “learning” experience could emerge; I called it a sort of “machine for churning the Father’s rational discourse into the Daughter’s contrary fantasia.” I was obsessed with Freud’s dictum that men are motivated by ambition, and women, the erotic, and although I was certainly immersed in the world of the erotic, I also considered myself every bit as ambitious as my male classmates. The “moments of learning” in my essay are those instances in which I sought to challenge this apparent contradiction between ambition and eroticism, while at the same time trying to embody, as a feminist, both impulses within myself.

Jim: My big learning experience, as recounted in my essay, came when Ronald Reagan taxed my graduate stipend the same year the Supreme Court reaffirmed the ‘criminality’ of homosexuality in the Bowers v. Hardwick case, imposing a civic burden on me, while denying my right to exist. That’s when I knew that the lines between culture, politics, intellect, and social definition were always intersecting–a truth that my experience in that time and place had already been teaching me in other ways.

Mary: Buffalo’s English Department was an incubator for new ideas, and it was dedicated to a kind of radical originality, a quirkiness that helped me feel validated in my own odd turns of thought and imagination. Overall, the understanding that the artistic could be thought in concert with the critical, that artist-intellectuals were something we could become, and that the terms were not opposed to one another but deeply companionate—that was truly formative, and something I continue to cultivate in my own classrooms to this day.

I love Mary’s notion of the “deeply companionate” relationship between critical analysis and artistic craft. This is a territory that I believe many readers will want to investigate, especially if they (like me) are not as well versed in the deep bench of writers and literary references that you know like the backs of your hands. If you had the opportunity, how would you wish to see this relationship—between critical analysis and artistic craft—expressed, for example, in friendship, in teaching, or in political discourse?

Jean: Some of my most valued friendships, old and new, are enacted in writing groups, where trust and even love among the participants makes for a balance of affirming support and challenging criticism.

Mary: In teaching, we could introduce our students to the pleasures and possibilities of the essay as an art form they can all be enjoined to create rather than remain inside the staid confines of that sad little program of five paragraphs we were told was the essay from K through 12. Imagine being encouraged to wander, to start from some unaccustomed point of view, to find the thought inside the thought inside the thought, or better yet the feeling inside the thought, or the thought inside the feeling. To incite students to think analogically, to make connections, to cross-identify, or juxtapose—appositional thinking (a.k.a. assemblage and collage) really is a powerful antidote to oppositional posturing, the presumption of “two sides,” and the territorialism that comes with it.

Mary: In teaching, we could introduce our students to the pleasures and possibilities of the essay as an art form they can all be enjoined to create rather than remain inside the staid confines of that sad little program of five paragraphs we were told was the essay from K through 12. Imagine being encouraged to wander, to start from some unaccustomed point of view, to find the thought inside the thought inside the thought, or better yet the feeling inside the thought, or the thought inside the feeling. To incite students to think analogically, to make connections, to cross-identify, or juxtapose—appositional thinking (a.k.a. assemblage and collage) really is a powerful antidote to oppositional posturing, the presumption of “two sides,” and the territorialism that comes with it.

Jim: I think the structure of our book reflects a kind of politics: three different essays, each self-contained, each given roughly equal time, each in dialogue with the others in ways explicit and implicit. Mikhail Bakhtin–a literary theorist who’s mentioned in the book–held that what he called the “dialogical” imagination formed the essence of political life, embodying the multi-voiced sphere that stands against authoritarian structures. The Reagan years felt to me nearly as much like an authoritarian regime as the Trump years do to many now, and forging a queer identity then–when the word “queer” itself was still an epithet–felt like a dangerously creative and a profoundly political act. The book is an invitation to the reader to think about that.

A detail from Charles Burchfield’s 1935 painting, Telegraph Pole, illustrates the cover of your book. We see the old glass insulators that prevented energized wires from contacting each other. Indeed, Burchfield’s evocative titles (The Sphinx and the Milky Way for example) also form a parallel in my mind with the Armenian-American painter Arshile Gorky (The Liver is the Cock’s Comb; One Year the Milkweed) These titles reveal a subtle appreciation for metaphor that is embedded within a painter’s experience. Let’s fold a fourth voice into our conversation and allow me to ask you to reveal a particular work of visual art that embodies the energizing spirit of friendship, self-examination, or pursuit of discovery that encircles your endeavor.

Mary: For me the artist who embodies the energizing spirit of friendship is the American modernist, Charles Demuth, whose watercolors of gender-queer bodies, often bathed in atmospheres of the dance, or the circus, I saw for the first time as a 12-year-old. My mother had taken me to The Barnes Foundation when it was still located in Merion, PA, and there I discovered painting after painting by this artist whose name I didn’t know but whose figurations of movement and of love literally impressed my tom-boy body with the most delicate of embraces as my mom and I moved together from room to room to room.

Jim: What a lovely question–and funny you should mention Gorky, as his work hangs in Buffalo’s Albright Knox art gallery beside lots of Burchfield’s work. But for the embodiment of our project in the visual arts, I would point the reader not to painting but to cinema–namely, to Vincente Minnelli’s classic musical The Band Wagon from 1954, about the project of putting together a whole, integral piece via the collaborative, spontaneous juxtaposition of multiple “separate” performances. One of the most memorable of these is “Triplets,” a hilarious and beautiful number performed by two men and a woman (Fred Astaire, Jack Buchanan, Nanette Fabray) in infant garb that in a guise of sibling rivalry secretly celebrates the trio as an alternative to the singular, the dual, or the many. We three have been known to perform this number together in public, and it is very much in the spirit of the book.

Jean: I recall an extraordinary exhibition on friendship we saw in 2015 at the amazing German Hygiene Museum in Dresden. In addition to endless shelves of diplomatic gifts between Germany and its allies, masses of images from social media, a map of letters between famous friends, and a tribute to our best friend the pet, the show featured five centuries of paintings (most reproductions), each depicting friendship. The painting I really loved was Swiss artist Louise Breslau’s The Friends (1881), a trio of women, the painter in profile at work on her canvas, and her two friends, artist Sophie Schaeppi and singer Maria Feller, sitting unsmilingly at a table, as though resolutely refusing to offer up feminine agreeableness to the would-be male voyeur. Is it their shared artistic pursuits that cement their friendship? That you can’t entirely know the answer to this seems signaled by another member of the circle, a scruffy white dog, its muzzle archly turned inward in a gesture of reticence.

I love these examples from film and painting that so refreshingly inspire other forms of interconnection. Yes, friendship is a trigger for the cultivation of wonder, and a springboard that gives us courage to take action, or to deepen our work in unexpected ways as we learn from another’s discipline. Your book calls for this kind of freedom. Thank you.

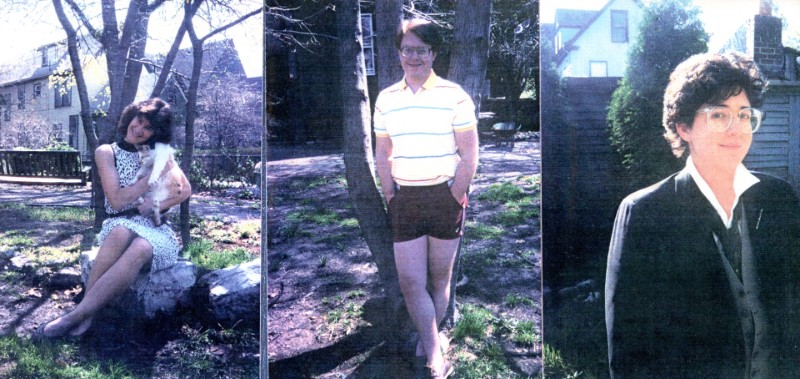

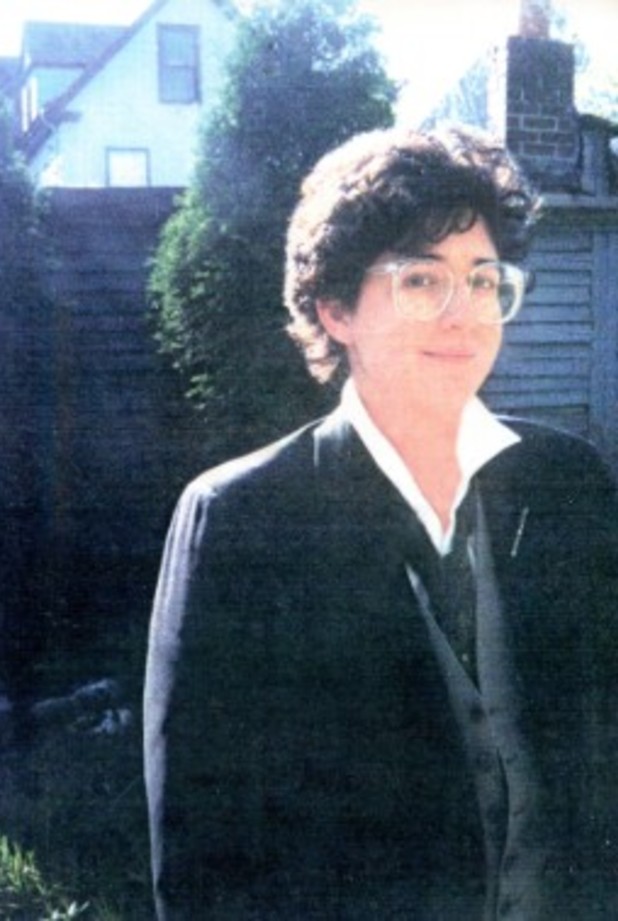

Featured photo: Mary Cappello