Jess Arndt on Writing Honestly

Author: Chelsea Catherine

May 13, 2018

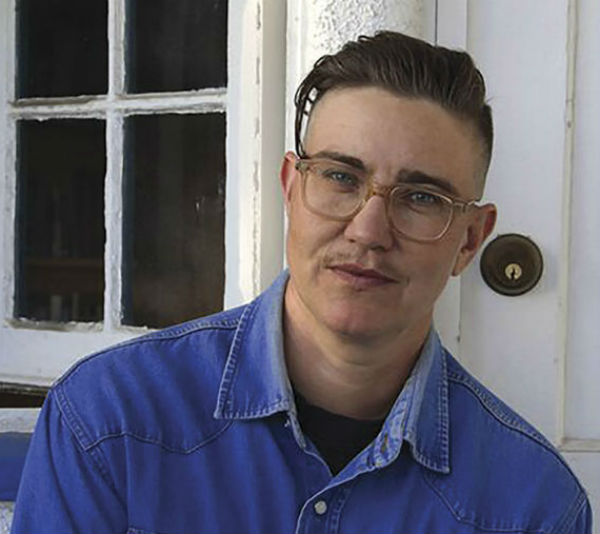

Jess Arndt is the author of the book of short stories, Large Animals, recently published by Catapult. She received her MFA at the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College and has been published in a multitude of journals and literary magazines. Jess has also taught in many places, like Rutgers University in New Jersey, where she was my writing professor not once, but twice!

At Rutgers, students knew her for her welcoming, funny, and kind demeanor. Her classes there were always full. Jess was the kind-hearted teacher—finding ways to give critique without making you feel stupid or put down. In addition to being an awesome teacher, she also wrote the graduate recommendation that got me into my MFA program (as I’m sure she’s done with many others). After her days at Rutgers were over, she moved out to LA. Since then, she published her short story collection and has a new baby with her partner.

Her recent collection, Large Animals, is a Buzzfeed Best Fiction Book of 2017 and an Entropy magazine Best Book of 2017. The collection jumps from the tri-state area to the desert, following the lives of people we don’t know but who feel intimately familiar. The prose is succinct, sharp, funny in a way that sometimes hurts. Jess talked to me a little about the book and about the way her writing comes together in her short fiction.

For me, place was a big part of your short story collection. With “Moon Colonies,” “Jeff,” and “Been A Storm,” I was right back in the tri-state area. Not just from the sense details and setting, but from the way people spoke, how they treated one another, and even the way you used language. How much does setting influence you when you write? Do you draw on places you are familiar with, or do you imagine new ones?

I think the best way I understand setting is that each time I write, I can only do it by trying to access groups of feelings created by the common experience of having sensory pads over our bodies (that we drag around with us wherever we go). Writing is like wringing the body out: you collect what’s there. I rarely think of “setting” per se, but do think of rubbings, as in how has a place rubbed me? Or where. Moving to New York was a big deal for me (as it is with most people who aren’t native NYers). I feel my body differently in New York than in other places. So it makes some kind of sense to me that writing that occupies a NY trajectory would have a different cadence, or embodiment, than say the California desert writing that comes later in the book.

Another big thing I noticed right away (and appreciated so much) was that your opening story, “Moon Colonies,” is a story about a woman loving/liking other women. Reading this story was like a big sigh of relief for me. I’ve been discouraged by others from writing these relationships because they think it will put me in a very specific genre, and “limit” my audience. I personally think that’s bullshit and am curious what advice you’d have for any wlw writers out there?

This is a big one and every writer or maker will inevitably have to answer it for themselves. I’m glad it felt that way and of course think writers should never listen to anyone telling them what “not” to do. Large Animals could not have been written if I tried to scrub it of queerness to somehow make it more universally palatable. I think the question of audience is deadly to writing. But you’ll find other people will often claim to want you to think about it, usually as a sideways way of saying you’re doing something uncomfortable for them.

Actually, I don’t think the subjects we choose to write are what limits audience, most of the time. But it’s possible that certain texts are more open to human experience than others, and that as humans, we crave this. Giovanni’s Room, for instance, by James Baldwin. The Argonauts, by Maggie Nelson. No one would ever say these books are too much about alternative relationships. But they are brimming with difference that offers bridges to other experiences of difference, and in this way both are extremely queer.

When you first began writing, were your works wlw? How did you navigate that in the publishing world? Where did you find support?

My first writing was lonely, tortured, teen age, gay. The kind of stuff you write when you’re trying to survive. At 13 I had Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes stuffed under my pillow—there was the pseudo-hidden, (to me smoldering) love story between Idgie and Ruth. Otherwise, I couldn’t find any books to reflect what I was going through. I remember desperate bus rides to Seattle’s main Public Library, then camouflaging myself in the stacks; it was the early 1990s. Later, I wrote a novella set in 1850s SF about a kind of fledgling trans character, or if not trans, someone who was/is between. My writing now feels less “identity”-based, but is still equally restless around bodies and form. In all of this queer community has been extremely important as a kind of basic support organism. Unfortunately, the way our society currently functions means that exactly these peers and mentors–who are also struggling bodies (ie female, POC, queer)–are similarly, or even more spiritually/psychically/emotionally/physically taxed, are spending all their juice trying to make opportunities for themselves/stay afloat.

For that reason I value the people who have helped this book along—Maggie Nelson, Lynne Tillman, Amy Sillman, Justin Torres, Dorthe Nors, Michelle Tea, and my agent Marya Spence and editor Julie Buntin—immensely. These are people who are giving even when they themselves are running on fumes.

A lot of your stories have a not quite real feeling. I guess you could call it magical realism? Things are happening, but sometimes the reader is not sure if they’re entirely real– like with the walri in “Large Animals.” I’m curious if these magic moments come out of thin air for you, or if they are thought on, more imagined based on what might make a good metaphor for the story.

Well first off, after struggling with plotting things for years, I took Marguerite Duras’ advice in her 1993 book Writing completely to heart. In it she says: “I believe that a person who writes does not have any ideas for a book, that her hands are empty, that her head is empty, and that all she knows of this adventure, this book, is dry, naked writing.” I mean, wow. Terrifying and freeing. To think that you could be doing the right thing by going into a piece empty? To think that scratching around–feeling bored, or lonely, or horny, or confused–is not only valid but actually valuable to the work? So anyway, I rarely know what I’m doing when I’m in a story. Usually when something like the Walri arrives, I think it’s ridiculous, but I keep it in, because if I took it out I wouldn’t have anything on the screen at all. And then very slowly the story starts to unwind–or mess around into its eventual form–from there. I guess you could say I work by somehow trusting the subconscious/unconscious more than anything else. I mean unconscious in all shades of the word—drunk, knocked out, dreaming…

But also the other thing I wanted to say is: I totally agree with you, the Walri have a mystic feeling. But from my end—as the body writing it—the appearance of the Walri was somehow the most direct, most lived way I could convey the experience of having a protuberant, disobedient, unreliable body. It’s a funny contradiction, but here the imagined and real are two sides of the same coin. Walri as fantasy, as morphing sexual appendage, just there.

“Jeff” was by far my favorite story, and not just because I went to Rutgers and hated all the white straight guys bro-ing around drunkenly. There’s an element of vulnerability in the narrator in that story. The things that she thinks of doing to Jeff are weird and dark and sometimes embarrassing. I think those weird, dark things are what make a story real, and what make a story good. My question is– do you ever worry what people are going to think of your narrators in stories like that? Do you ever worry someone is going to put the book down because of a narrator’s actions?

I’m human and so I’m often grossed out by myself, by my thoughts and actions, and scared of what people will think. But I’ve also found–through trial and error–that the best place for me to get to in a story is that gruesome little ledge. You’re totally right that for me, “Jeff” had some of those ledges. In other words, at times writing it made me feel queasy. When the narrator pushes the marbles in Jeff’s ass, for instance. Or treats Sheila poorly.

“Can You Live With It?” (further on in the collection) is another place this happens. The story, like most of the stories in the book, is dealing with a sense of being outside, or apart from. In this case, also like many instances in the book, the narrator feels muted by the confusion of their body’s illegibility to the world (but also to themselves). Three-quarters of the way in, the narrator (drunk, sitting in a strip club) says to their friend: “I can’t even get AIDS!” and this was a hard line for me. I mean, I came of age into a queer culture that was freshly traumatized by AIDS/still in the midst of the AIDS crisis. So the idea that the narrator wants the chance to be sick, to die even, as a way to feel all the way human…writing it, that voice sounded so self-pitying, so naïve. But it bubbled out of me. I had accidentally written it down. Now it was there. Back to question # 2., not everyone will like what you or I write. Sometimes we may not even like it ourselves. But if we’re really paying attention to the work, I’m pretty sure we still have to write it.

“Can You Live With It?” sometimes pushed those buttons for me, too, but in a way that felt really satisfying. One of my favorite lines from that story is, “Whenever men are near us we try to outspend them, peeling cash from every financial obligation, our rent, car insurance, whatever, all of it, dumping each bill shyly down.” There’s an element of insecurity there, like the narrator feels like they have to prove they deserve to be there. So many of these stories have this element of being on the outside looking in. Can you talk a little bit about insecurity and how it relates to writing and queerness and writing queer stories?

So interesting! I kind of just feel like the answer is “Yes.” But maybe there is something particularly corrosive to self-identity about moving through the world in a body that does not fit into the male/female divide (of course none of us really does). The word coming into my mind right now is: diphthong. A vowel that first sounds one way, then ends up another… in other words, a weird space in-between. When your daily experience consists of a hazy, bendy, but very active engagement with gender binaries that never resolves, but is always printing back on your body, I think it’s hard to ever really feel “inside.” An example: I was recently traveling from Oaxaca back to the US with my partner and our 9-month-old baby. His name is Osa. My name is Jess, but on my passport, Jessica. At the US Customs in Houston, the agent looked at Osa in his stroller and said “Hello, Jessica.” His brain just refused, was happier to shrink my age by 40 years than call me “she.” This double-sight is often funny, and should be freeing but sometimes isn’t. The body memory of being “other than” (normal, readable, desirable, successful, etc etc) especially when constructed over years and years, is hard to shake.

Can you tell me a bit about your most recent project and what you are up to right now in your life?

Right now the ratio feels like 99.999999 percent new parent, .0000001 percent everything else. Another way to think about it? Trying to do all your normal stuff (like get back to your questions that I’ve really been wanting to answer, for instance) but doing it while butterfly stroking through glue. But I am working on a writing project I started last year while in the Arctic! I’m interested in/devastated by climate change, by a planet that is transitioning, and what that means to and about our bodies (which are also transitioning) while we’re here.