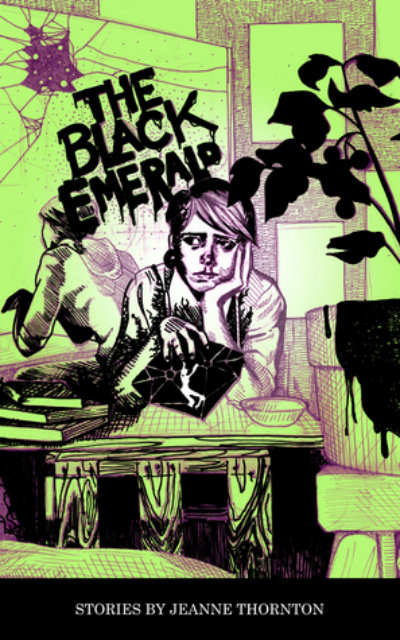

‘The Black Emerald’ by Jeanne Thornton

Author: Cat Fitzpatrick

March 28, 2018

Jeanne Thornton’s book of short stories, The Black Emerald, is fantastic, meaning both that it’s very good, and also that it’s really weird. What’s weird about it? Well, a lot of weird things happen–in the title novella, a love-lorn teenage cartoonist finds a magical gem which grants extraordinary artistic power, but also takes over her dreams; in another story a woman’s annoying ex-boyfriend uses a Van de Graaf generator to move himself into a dimension inside the walls of her apartment. The real strength of the book, however, is the way it is able to make even the most everyday occurrences seem strange.

Let’s take a small example, from the opening of a story called “Staying Up For Days In The Chelsea Hotel”:

Even over the office phone, notoriously dodgy since some long-departed Bad Intern had spilled her morning mix of cold coffee and cold gin into the receiver, and even given the eight years during which we hadn’t spoken, it was easy to identify January’s voice. She talked like a surfer, one whose mind had been so blown by the waves that she could only whisper like beach sand moving over itself.

Rotten Apples Press, I answered.

What is uncanny about January’s voice? We get quite a lot of concrete information about it–presumably, it’s quiet and raspy with a California accent. Nothing inherently weird there. Maybe what’s really weird isn’t the voice, but the way the narrator reacts to it. But the oddness of her impression (”like beach sand moving over itself”) is carefully pitched against the gossipy-comedy-novel-of-office–life tone of the rest of the paragraph. This pitching lets us know we are not listening to a speaker who is trying to be poetic or kooky: she’s trying not to be and failing. What’s strange here isn’t exactly voice or perspective, it’s more concrete than that: it’s a strange relationship.

This relationship is sketched out with dexterity and concision. The speaker’s tendency to romanticize and narrativize, despite her attempts to be normal, is evident not only in her description of January’s voice, but also in such small details as the capitalization of “Bad Intern.” The way that January’s spacey evasiveness acts a lure for this tendency is evident too, as are the narrator’s attempts to resist–her carefully neutral “Rotten Apples Press.” Everything that will be drawn out into deep weirdness in the rest of the story is already present and peculiar in a short paragraph that does no more than describe someone answering the telephone at work.

This ability to so deftly ground the reader in quotidian strangeness is vital to the success of these stories. When weird things happen, it doesn’t come from outside, as an invasion- the weirdness was already lurking inside the normal. It is this feature that makes Thornton’s stories so unsettling.

It’s also what makes this such a good book about queer, and especially trans, life. Probably my favorite story, “Putrefying Lemonade,” makes the connection clear:

Rhoda had always had the feeling that strangers sensed something terribly socially wrong with her, some basic hole in her character or some total hygienic flaw. So it was really cool when she came out as a trans lady and now suddenly she had something that in fact was terribly socially wrong with her, so no sweat.

“Putrefying Lemonade” has no supernatural elements at all–it just describes a trans woman getting into, and then getting out of, a bad hook-up with an older straight couple. But it feels more revelatory of the terrible wrongness of existence than any ten descriptions of eldritch monsters from beyond the bounds of perception:

The alcoholic woman was with some guy, a feathered blond man-without-a-shirt in a music video from the late 1980s. He looked as if he’d been sealed in a jar of liquor for twenty years […] The two of them had suitcases on wheels and wore white, freshly laundered T-shirts.

I’m telling you, people don’t do no meaner shit than on tequila, said the woman. That’s why they call it that. To-keel-ya.

Unexpectedly the woman turned full face to Rhoda, caught her eye again. Rhoda returned her stare and the woman smiled.

Get it? she hooted. TO-KEEL-YA.

This woman, I’m pretty sure, is worse than Cthulhu, and this world, which is more-or-less ours, seems, as Thornton writes it, weirder and scarier than anything we’d have to go to the trouble of imagining.

The Black Emerald

By Jeanne Thornton

Instar Books

Paperback, 9781682199084, 178 pp.

September 2014