‘Learning What Love Means’ by Mathieu Lindon

Author: Andrew Blackley

September 18, 2017

I still don’t think I know what love means, but I can recognize some of the avenues others have taken to come to find out. I’ll admit I did receive a couple of looks when fellow travellers with wandering eyes (and maybe a peeping Tom or two) read over the cover of the book as I worked my way through it over the past few weeks. I surmise that they surmised I was reading a self-help book, or worse: a self-healing book. To belabor the point: I think they may have thought that by reading it, I was making an outward profession or confession of my intention or desire to seek out help or healing tools. Of course it’s true that, as they are written, books can be confessions, but I can’t easily envision coming to literature in order to cure an ailment or learn a trick. Instead I find it more attractive to do as one does with analysis: to be in it and be a part of it. To be partial to it, partialized by it; to want to be there, to know that it’ll never work and of course that’s what works. So yes, one day I should love to learn what it is that love means. Until then books and authors and keep alive the question-and-answer (or, ailment/cure) question as an important one to me. I’m in good company: part of Lindon–the versions and stages of him that he recalls for us here–has certainly looked to The Book in its two (+) forms for answers: his father was Jérôme Lindon of Éditions de Minuit, the other being (the) Michel Foucault.

The author and his confessions effervesce to the surface sleekly on every single page of the book with such skill that recognition only comes in hindsight, and it is only through hindsight that the most obvious claims and relationships become truly obvious.

“Tears in My Eyes”, “Encounters, Rue de Vaugirard”, “Them”, and “Those Years“–the section titles in full–give composition to the modes for where best, and when best, to elevate Lindon’s para-confession to the realm of pater-confession. They are the certain stages for Mathieu’s education: the most crucial scene being set at the apartment (Rue de Vaugirard) where we (which must be the 20th century grandchild of the formerly royal we), politely experiment and find ourselves savory in the process. With sections “Them” and “Those Years”, Lindon narrates the scenes and the tones with an expertise so matured that the implications are easily confused with the communication–not to mention my own speculation. Every perspective maintains itself as logical, sound and–naturally–entirely not. Have you, deep in story, ever spoken so surely and so confidently that your cadence has a composition entirely devoted to the texture of the spoken word, existing regardless of any need for breath? It can be spectacular to find yourself as speaker or receiver at such an occurrence, and in the sections “Them” and “Those Years”, the end comes to us. That way you have the pleasure of seeing both.

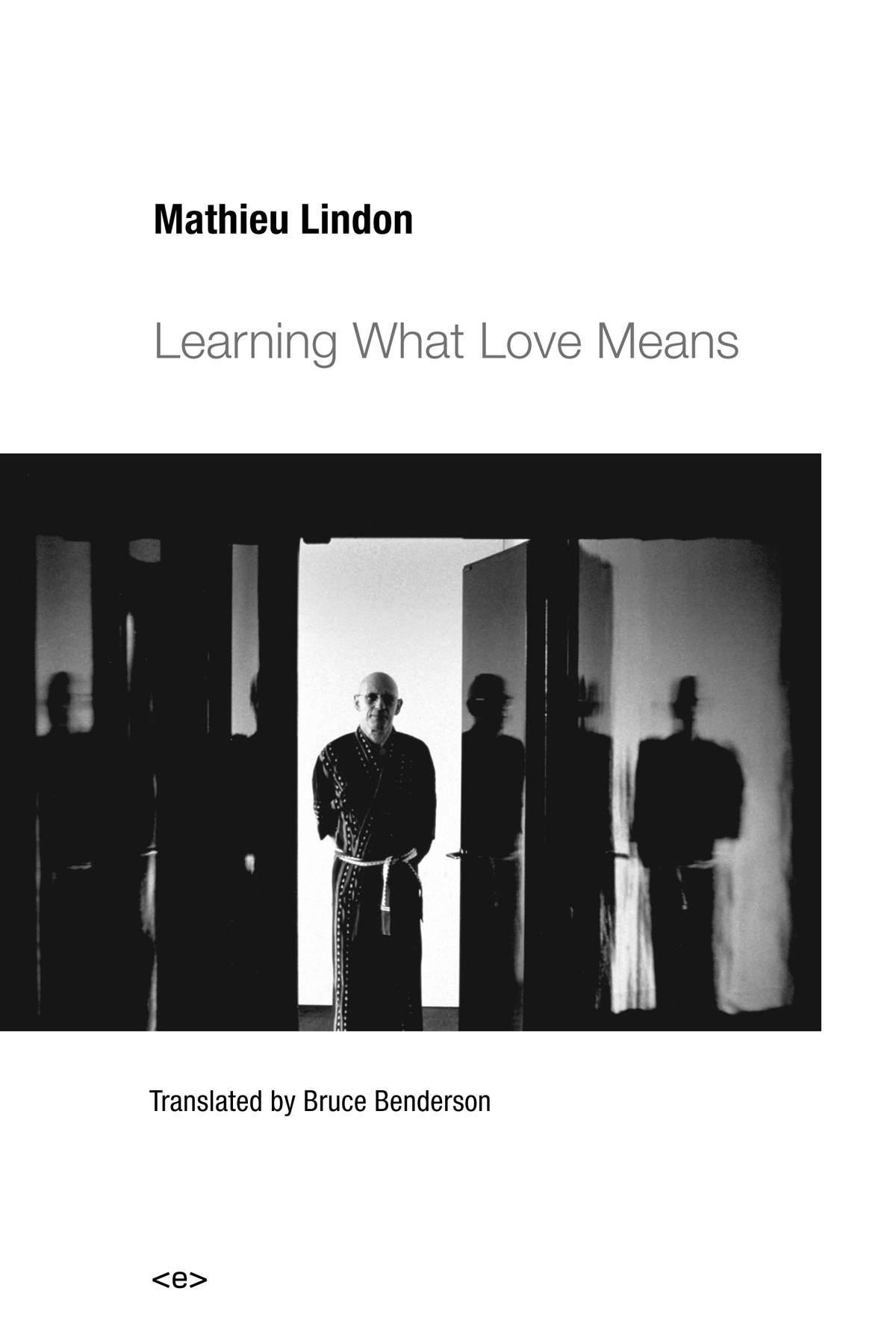

Lindon navigates himself as his narrates and acknowledges the main characters: Hervé (that is, the Hervé Guibert: friend, author, homosexual, photographer whose work happens to be featured on the cover of this Semiotext(e) publication. Man of letters); Jerome (father: publisher, fellow, albeit-unwitting?, homosocializer. Man of publishing); Michel (kimonoed subject as photographed by Guibert: long-term resident except when he is not, and when he is not, the boys are playing in his apartment. Also homosocializer. Also homosexual. Man of langue?). These characters (and there are plenty others) in Learning What Love Means are surprisingly short on dialogue. The expressions of individuality reside entirely as context and context-building processes for Lindon, and yet there’s not a sliver of solipsism, neediness, or narcissism. It’s quite honestly refreshing and, well, new, though it is reminiscent of when you explain to your analyst a particular exchange or situation which by default is from the past though not quite yet (or no longer) a memory. It’s less an object to be recalled, or confessed, but a semblance of a tableau resting at some focal point that evades reference. Your eyes may droop as you narrate the scene (that is, this pseudo-memory) you had with so-and-so that seemed so meaningless in the moment; you accompany the narration with dialogue that would never have been committed to memory. In those moments when there was dialogue that can be recalled, you come to know later exactly, in the narration, what they said with their tongue and what they meant beneath it. (Note the certain language that “embraces” Lindon from a colleague one day as he arrives at the office after “situation X.”) Speech is always operating as a proxy–this time, proxy for cruelty.

Proxies generally are far more interesting than merely replacement, and in saying so I can’t help but mention: an idea repeated is a new idea. During and after late adolescence, Michel seems to have been Lindon’s (or, then: Mathieu’s) major proxy. Later we follow his experiencing the publication of The Use of Pleasure and The Care of the Self—both fine phrases for two significant ways of seeing the proxy process: First it is the domination and transmutation of that which we (might) enjoy; and the second, perhaps, a “reading” alongside and the ways in which we’ve witnessed the narration of any life.

The major stakes of the volume is the position amidst the classical exchange between the poles many of us know: “Uncle” Foucault–who is, of course, the kind of uncle with whom you share no recognized biological or marital relation–and Father. The overlay is imperfect, but one might dumb down the two as ars erotica and scientia sexualis. For it is, after all, Foucault–who, it should be mentioned, in Lindon’s book himself says very little of the work we know of him today, nor does Lindon explain it on his behalf — who has said elsewhere (1983, in interview with Charles Ruas): “I believe that… someone who is a writer is not simply doing his work in his books but that his major work is, in the end, himself in the process of writing his books.” It may be the case that for Learning What Love Means the phenomenon we elsewhere have named “autotheory” (though perhaps we could ask of ourselves what it might mean to begin calling out: autho-theory) could be just as effectively be called Narrativity.

The infamous/famous Bruce Benderson contributes as translator. In this interview he has this to say:

A writer has two things to master. He has to develop his craft–which usually comes much earlier in life than the second half. And then he has to understand his subconscious enough to have something interesting to say. Something which has a wholeness and integrity to it. And no matter how many hours you spend in writing school, no matter how much money you spend in writing school, you will never never never achieve that sense of integrity and self-knowledge that you need in order to write a novel. Artistic creation is a mediation between your conscious life and subconscious life. You do not know what you’ve created until you’re finished and have time to distance you from it. Because you’re playing with threatening material–material you cannot stand to make conscious, and that you have to express this way. You have to play cat and mouse with those energies. You can’t grasp them directly. Because they’re too disturbing, too disruptive.

Without question, any threatening device, and hopefully one that threatens divides, is attractive. Gerald Doherty wrote in “‘Ars Erotica’ or ‘Scientia Sexualis’?: Narrative Vicissitudes in D. H. Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’” (The Journal of Narrative Technique, vol. 26, no. 2, 1996):

Foucault identifies confession as the Western strategy for eliciting truth about sex, exposing not only what the subject wishes to hide, but also what is hidden from him or her. Indeed, Occidental literature is essentially a confessional genre, “ordered according to the infinite task of extracting from the depths of oneself… a truth which the very form of confession holds out like a shimmering mirage.” (History 59). It institutes analytical introspection as the form of constructed experience, and interrogation as its basic strategy for establishing sex as the hidden clue to identity.

I’m convinced there exists a pole for which Benderson, Foucault, and Doherty may together orbit. In considering where that apex may orbit I am reminded of a statement from artist Nayland Blake: “This leads back around to sex because I believe that there are two types of people: people who fuck to confirm an idea they already had about their identity and people who fuck to explore all the possibilities of their identity…” It seems here, with Matheiu Lindon’s Learning What Love Means, we have an answer presented clearly: we are capable, complex people, and we figure that out along the way–both ways. Lindon: “I’m a necrophile: I keep loving the dead. Like a teenager who can’t resist masturbating, I can’t help it. Necrophilia isn’t a sexual vice but an affectionate affection.”

Learning What Love Means

By Mathieu Lindon

Translated by Bruce Benderson

Semiotext(e) / Native Agents

Paperback, 9781584351863, 240 pp.

September 2017