Writer and Philanthropist Chuck Forester on Gay Sex in the 1970s

Author: Edit Team

May 30, 2017

“In the 70s, society labeled gay men irresponsible hedonists, so we proudly owned it and by declaring our love of sex we made a political statement.”

1970s San Francisco holds a special place in the gay imaginary. It was a beautiful, relatively liberal metropolis, where gay men from all over the world could commune and explore their true sexual and romantic selves, somewhat free of the conservative constraints that gripped large swaths of the rest of country. For a sizable community of young gay men, San Francisco was a special sort of Xanadu

Writer and philanthropist Chuck Forester explores this idyllic moment in gay history with his candid new novel, Our Time (Querelle). Set in the Castro in 1971, the novel is a Bildungsroman about a young gay Midwesterner exploring the sexual delights of the Golden City.

Forester took some time to talk with Lambda about his novel, his philanthropy work (he has gifted a million dollars to Lambda Literary), and his personal memories of 1970s San Francisco.

Have you read any of the other recent books that deal with San Francisco in the 1970s–I am thinking of Cleve Jones’ recent autobiography? How do you feel your book relates to these other books?

Cleve Jones has just written an outstanding book about the politics of the early 70s in San Francisco, but there isn’t much else about the era that I’ve seen because the men who would have written that history are dead. I am a 38-year HIV/AIDS survivor, so I wrote my story to fill part of the gap. I also did it to honor the amazing men of my generation who believed gay men should celebrate their sexuality and see sex as their gift and share it with friends.

In The History Boys, the character Rudge says, “History is just one fucking thing after the next,” but there have been nuggets of time in history (or in the case of the early 70s, in San Francisco), magical moments in time that changed the course of history. Those years in the early 70s changed the way gay men see themselves due to the perfect convergence of thousands of gay men fed up with having their sex demeaned and a beautiful city abandoned by the middle class that didn’t judge and welcomed sexual minorities. Just by crossing the city limits I, who’d repressed sex my entire life and beat off to Playboy in hopes of going straight, by crossing that line I could look at the most heinous part of me and I discovered I was a healthy sane male of the species. At a time when gay people could be fired and lose their family and friends if their sexuality was discovered and a time when Americans were bombarded daily in churches, schools and the media with the message that homosexuality was sick, horrific, and contagious, some gay men were adventurers.

We were not just looking for places to be free, but to support our jumping off the cliff; we sought out other times in history and other cultures where homosexuality was honored and where gay people were seen as shamans. I was not raised by gay parents and no level of education told me about how gay men lived, so I had to figure out what it meant to be a gay man on my own.

I became a full blown gay man in three ways. First, I started my conversations with fellow strangers in San Francisco by sharing our coming out stories. That gave me a glimpse into the psyche of gay men. The second were three friends and lovers who had come to terms with their sexuality beautifully and they served as excellent role models. The third was through sex. With my generation given free license to have as much sex as we wanted, I worshiped men’s butts. But mostly I was intrigued by the way a man responded to my touch. In the first three years I was out, I slept with more than a thousand men and seeing how they, when naked, treated me and themselves, I learned to respect myself and how to love a man.

In 1991, I volunteered to lead the gay and lesbian fundraising campaign for San Francisco’s New Main Library because I wanted to show the big money in town, like the Doris and Don Fishers who supported the Opera Symphony and Modern Art Museum, that my community could hold its own as civic donors. Once I got involved I realized that history is fragile and our history had been wiped out more than once by zealous tyrants and the Catholic Church.

Our LGBTQ culture has no Bible of ancestor stories, nor do we grow up with bedtime tales of our parents’ favorite Greek or Chinese gods so I felt it was incumbent on me to raise enough funds so that the Gay and Lesbian Center would be a comprehensive repository of GLBTQ history. The last such repository, the Magnus Hirschfeld collection in Berlin, was among the first books burned by the Nazis.

I and a team of extraordinary men and women was raising money during the height of the AIDS epidemic, hundreds of my friends were dead or dying, and I made sure that our fundraising materials and our asks were clear, that we were not asking for a dime that would otherwise be spent on AIDS. Our initial goal was $1.3 million, and in the end we raised $3.5 million, some from as far away as Europe, which said loud and clear that our community wants to know its history and preserve it.

I hope a queer person who hasn’t been born yet chooses the early 70s in San Francesco as the subject of their PhD thesis because in those short years gay life transformed from frightful lives of shame and guilt to lives of hope as we became real to ourselves and the rest of the world.

Why did you decide you to write a novel instead of a biography?

The decision to write a novel did not come easily. I’ve been writing my entire life; I took a typing class in high school and I bought a Correcting Selectric in college. Most of my early writing was correspondence, if anyone remembers the days of long letters. In San Francisco I wrote city planning documents. As Dianne Feinstein’s assistant, I wrote five to ten letters a day for her signature that responded to constituent letters and I was a pro with spin.

After retiring I went back to school and got a Master of Fine Arts in Poetry, my true love. I shied away from novels because I knew I couldn’t plot my way out of a paper bag, but the story of the early 70s in San Francisco is a faerie tale of a magical time and a novel allowed me a greater range of complexity and the chance to develop strong characters. I took a risk and the final novel took four years and six completely different drafts. Through all of it I had the finest editor in the land, Don Weise, guiding me.

Did you learn anything about yourself as you were writing the novel? Any moments of self-discovery?

As I wrote the novel, I was surprised at how much I remembered about the man I was in the early 70s. I learned I was competitive, even though most of my life I have never competed for acceptance or in team sports. When describing [the novel’s protagonist] Paul’s sex life, I realized I was competitive in bed because the most rewarding sex for me was when both of us were competing to out-pleasure the other, like the night with a Brit at the Black Tulip in Amsterdam and with Rusty Dragon at the Hothouse in San Francisco. Those nights, I used every trick I learned from other men to please the man I was with: if you’ve done that to me, let me show you what I’m going to do you. Unlike sports with winners and losers, in the game of sex both partners win.

I also learned I had standards. One might think someone who had as much sex as I had, had no standards, but I do. Mine came from my Unitarian-Universalist upbringing: be kind, be honest, honor others and take responsibility for your actions. As I wrote I realized I hold gay men to a higher standard: because they have treated me with such generosity, I want them to be perfect. When I looked back at me in those years I realized in bed and out I’ve always been a gentleman.

I had to press myself to give Paul the strength of a leader because I’ve never seen me a leader. My deep-seated feelings of inadequacy come from a father who hadn’t a clue who I was and an older brother who from the time I was four made sure I understood that I was weakling and I didn’t have what it took to be a man.

There were times when I was passionate about something. In high school I rose through leadership roles to become the chairman of the national board of LRY, the Unitarian-Universalist Youth Organization. In graduate school, the professor chose me to be a team leader for a studio project. When I did that I didn’t see myself as a leader; I just loved what I was doing. I took responsibility for fundraising for the Gay and Lesbian Center at the Library because AIDS was killing my friends and I had to do something, but I saw myself not as a leader but as a cheerleader for an extraordinary group for lesbians and gay men that I was guiding. To make Paul a leader on the page I had to accept that I am a leader.

What is your relationship to contemporary gay San Francisco? Do you still consider it home or a cultural gay mecca?

Since I was twelve, I was raised essentially by four parents (curious story/wealthy heiress) in three homes, so my sense of home is vague at best. Today I can do it my way and I have homes in San Francisco and Sebastopol that I share with two standard poodles, Darwin and Ulysses, and with my family: my son Seth, his girlfriend Cassandra, my granddaughter Taija; my amazing friends, my masseur, my trainer and my acupuncturist are always welcome.

Before moving to San Francisco, I thought San Francisco was a city of beatniks, low-lifes and Rice-a-Roni, but when I was on my way back from a job interview at the San Francisco Planning Department I passed three of the sexiest men I’d ever seen standing casually in front of Flagg Brothers Shoes on Market Street. The idea of gay hustlers had never occurred to me and when I stared at the men in disbelief one of them cruised me and it freaked me out but at that moment I knew San Francisco was the city I’d been looking for. After I moved with my pregnant wife to San Francisco, City of Night caught my eye when I was in the library trying to find anything that would tell me being gay was OK. I opened to a page of drag queens and hustlers which wasn’t what I was interested in, but they were there in print, so I knew gay people existed! I grew up with a baked-in responsibility to raise a family and while I played around with boys in junior high and I had two bad gay experiences at Dartmouth, it took San Francisco, a wife, a child and a Volvo station wagon for me to finally come out. Since I came out I have been eternally grateful to San Francisco for letting me be me and I have dedicated my life to enhancing San Francisco’s GLBTQ community.

I believe San Francisco, along with Provincetown and Greenwich Village, will remain cultural meccas; if those two were the brains of the movement, San Francisco was the guts. Some of the luster of our past has dimmed due in part to the loss of an entire generation and due to the passage of time, but our presence here is a state of mind and our queer roots go deep and permeate all of San Francisco.

Recent attempts to capture San Francisco, like HBO’s Looking and ABC’s When We Rise, have not fared well because they failed to capture the spirit of San Francisco: that quirky, irreverent sense that makes us a little crazy, and an impulse to make things right—that is who we are.

Gay men in San Francisco are more than a fucked up soap opera relationship and we are more than people plotting winning political strategies; we are jumping around, acting crazy and sticking-our-noses-into-whatever-smells good fools. I’m reminded of a tiny man with long white hair who dressed in a white 3-piece suit and stood on the corner of 18th and Castro in the 90s with a white toy poodle at his side and an accordion half his size around his waist. To me he and Emperor Norton are the essence of the San Francisco I love.

Your book centers on sexual liberation. Sexual liberation is something that oddly enough is not discussed that much in gay political and artistic circles. Why do you think it is important to focus on sex as an intrinsic part of the gay rights movement?

AIDS slapped gay men back to Victorian attitudes. Progress withered like a limp dick. The current political and artistic circles who aren’t talking about it haven’t evolved, so they’re afraid to publicly say that they love sex. I think our sexuality is intrinsic to who we are as gay men; its courses through our blood and feeds our imaginations. My sexuality gives me a unique understanding of the male body and with my sexual experiences.

I know bullshit when I see it. Anyone who claims otherwise can’t see it because even modern-day closets don’t have windows. My generation rode the crest of the 60s’ wave of free sex and drugs. On Broadway Hair showed dicks and pubes and Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice was a box office hit. San Francisco has always welcomed strippers and madams and The Summer of Love almost burst the seams of the Haight Ashbury with thousands tripping on LSD and sharing naked love randomly with each other in Golden Gate Park.

In the 70s, society labeled gay men irresponsible hedonists, so we proudly owned it and by declaring our love of sex we made a political statement. I remember the look of relief on the faces of men who said for the first time out loud, “I love sex,” like a great weight had been lifted. Gay men without sex are like Zebras without stripes and sex without gay men gets tedious.

I believe the men who were initially the most interested in moving to San Francisco in the 70s were men for whom sex was at their core because we had the most to gain. After lifetimes of repressing our sexuality, the city allowed us to freely express our love of sex, and that produced a denim/flannel carnival of ecstatic hedonism with some interesting sideshows that is seldom seen in history and that will not be repeated any time soon.

We have a long way to go with sexual liberation. America has a piss-poor track record when it comes to sex, starting with the straight-laced Puritans who first landed on our shores and the later generations of sex-denying Catholics and Protestants that haven’t done much better.

The last five years has seen a remarkable change in public attitudes about GLBTQ people but like coming out to our families, saying I am queer comes long before we say I take it in the ass. Young gay men today are freer with touch and talk openly about sex. They give me hope, but with Trump and Republicans hovering over them like a wake of vultures they have a lot of shit to contend with. I long to see the day when gay men believe sex is a pleasurable adventure they share with their friends as I do.

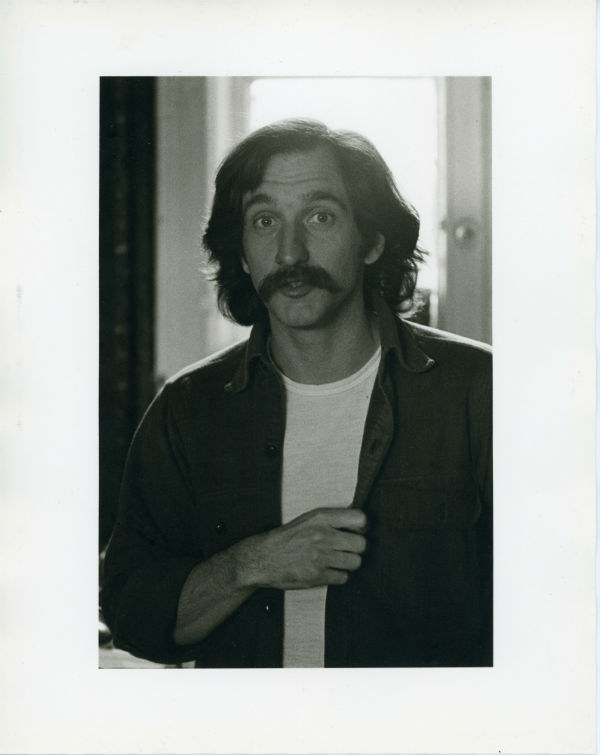

Can you tell me a little about the photo on the cover of the book?

The photo is Michael A. Schoch. Born and raised in Downey, California, Michael believed at twelve that it was his fault his mother died of cancer. At nineteen, his stepmother discovered that George, who was sharing Michael’s room, was not a just a roommate, and his father, an aerospace factory foreman, demanded that George get the hell out of the house.

With a couple hundred dollars between them, Michael and George bought a beat-up Chevy and drove through the night to San Francisco. Shortly after arriving, Michael came down with hepatitis and he spent five months alone in a room surviving on peanut butter and the Brussels sprouts he grew in the yard. Michael loved plants and the food they produce. On short notice, he could have a plate of delicious food that looked like a photo in a culinary magazine on the table in twenty minutes. A friend suggested he do food art.

With a couple hundred dollars between them, Michael and George bought a beat-up Chevy and drove through the night to San Francisco. Shortly after arriving, Michael came down with hepatitis and he spent five months alone in a room surviving on peanut butter and the Brussels sprouts he grew in the yard. Michael loved plants and the food they produce. On short notice, he could have a plate of delicious food that looked like a photo in a culinary magazine on the table in twenty minutes. A friend suggested he do food art.

He didn’t like bartending and started a landscaping business and in four years he, a natural with plants, was one of the most sought-after landscapers in the Bay Area. Two women landscapers with a client list of the richest in San Francisco and the Peninsula had lost the man who founded the company to AIDS, and they asked Michael to join them. He had just been diagnosed with KS and refused the offer. Had he lived long enough for protease inhibitors Michael today would be among the foremost landscapers in California.

Michael was one-of-a kind, with a smile people remembered and wherever we went, here and abroad, people stopped him to say they remembered his kindness. I saw him first as the day time bartender at Toad Hall but my attempts to meet him failed. The weekend before I met him, he and Lou Kief spent the day working on a cabin they were building in the far reaches of Sonoma County and that evening after dinner they split a Quaalude and were lying on their sleeping bags. Lou asked Michael if he had three wishes and Michael said he wanted a man to love, a son, and a helicopter, so they didn’t have to drive to the cabin.

The next Sunday I was at the cabin when Michael arrived and when he saw me our eyes connected as my son behind me played with his toy plastic helicopter. After our first date, when we couldn’t keep our hands off each other, we slept together every night. Our lovemaking was rambunctious and serene and that lovely fun lasted most of our relationship. My connection with Michael was so profound I am certain we knew each other in a prior life. For eighteen years I had what few man have: I had Michael’s unconditional love, even though some of what I did hurt him, for eighteen years.

Michael liked the better things in life so for my first birthday with him he gave me a night in a suite the King of Norway used at the top of the Mark Hopkins Hotel. For Christmas a few years later, with money he made growing dope at his cabin, Michael gave me a trip on the Orient Express from London to Venice. Michael planned an elaborate surprise fiftieth birthday party for me at the elegant John Pence Gallery. Two days before the party, he died. I was grief-stricken but I went ahead with the party and our large group of friends, my father and stepmother, and the head of the Chamber of Commerce and a few elected officials honored Michael by celebrating my birthday. That bittersweet day is the most moving day of my life. Michael has returned to me in dreams, one so realistic I grabbed his hand to make sure I wasn’t dreaming.

You are a big supporter of Lambda Literary. What is your inspiration for supporting our organization?

Words matter and books change societies. Our community needs a vital, unshackled writing community to survive and Lambda Lit provides it with a solid foundation. Over the last thirty years I’ve been involved with non-profits that range from large established ones like KQED to those that were just getting by, and the ones that excited me were the ones that were just getting started because I got off on that rush of new energy and the freedom to be creative.

Lambda Literary languished in the backwaters of our community for years; most people never heard of it. Tony Valenzuela brought a new spirit and name to Lambda Lit and he has energized the staff and our members and he allowed me to use my experience with boards and fundraising to help him turn Lambda Lit into an essential community resource.